Bernard Bosanquet, born October 13, 1877, was the first man to bowl a ball with a leg-spinner’s action and make it break from the off. Arunabha Sengupta looks back at the career and life of the man who invented one of the most intriguing weapons of cricket — the googly.

The first victim

July 20, 1900.

There could be no easier way to get to a hundred.

Bernard Bosanquet, who had stroked his way to 136 in the first innings of the match, was tossed the ball by Middlesex skipper Plum Warner. He tossed the ball from hand to hand and marked a short run up. He was not going to come charging in, bowling fast as he used to in the earlier seasons. He ambled in and let one soar with a slightly comical loop. Samuel Coe of Leicestershire, batting on 98, could not believe his luck. He rushed out to play it to the onside. And then it pitched.

Coe stood trasnsfixed as the ball broke the other way. It bounced four times before reaching William Robertson squatting behind the stumps. The Peru-born rookie wicketkeeper, playing in his first season, whipped off the bails. The googly had claimed its first victim.

Only, in those days, it was not called the googly. It was viewed with suspicion, often deemed unfair. It became known as ‘Bosie’, after its inventor. In Australia it was linked to deception, and was given the name earmarked for acknowledged rogues – the “Wrong’un”. The societal taboos of the day associated the term with felons, divorcees and homosexuals. And a googly was viewed with the same amount of distrust.

It makes sense to mention a curious coincidence in this context. One of the most famous wrong ’uns of the day was Lord Alfred Douglas, the author, poet and translator, and the favourite boyfriend of Oscar Wilde. Through no cricketing reason, his nickname was Bosey!

However, in spite of the misgivings and propensity to trivialise, the googly became a potent weapon, and one of the most devious in the arsenal of the leg-break bowler.

The development

It is perhaps an exaggeration to say that Bosanquet was the inventor of the googly. He himself acknowledged that bowlers had previously bowled this ball without quite knowing it.

William Atwell, the Nottinghamshire and England medium-pacer, had sometimes sent down a puzzling delivery that followed no rules, and so did the eccentric ER Wilson of Rugby, Cambridge and Yorkshire. AG Steel and the Australian Joey Palmer are also sometimes credited to have bowled one or two by accident.

According to a letter sent to Jack Hobbs by KJ Key, HV Page of Oxford and Gloucestershire often bowled genuine googlies as long ago as 1885, although never in a match — always after the fall of a wicket, before the new batsman came in to bat.

David Frith later drew a parallel of Bosanquet’s achievement with Wilbur and Oliver Wright’s claims to perfecting the first propelled flying machine. “Others had dabbled, though in the case of the googly ball, the instances were undoubtedly accidental. What Bosanquet and the Wright brothers had in common was that they are acknowledged as the first to succeed ‘in the field’. The flimsy-faced aircraft that stayed airborne for 12 seconds at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, on December 17, 1903, was the forerunner of Concorde; Bosanquet’s little mischief was handed on to a school of clever, determined South Africans and on through a line of exponents whose pleasure at fooling batsmen of even the highest reputation has been deep and incomparable.”

Bosanquet was the first to bowl the googly on purpose in a county match. And it took him as many as three years after he had stumbled upon its mysteries. In 1897, he had been fascinated by the ball which “is merely a ball with an ordinary break produced by an extraordinary method.” He was playing ‘twist-twosti’ at Oxford. The objective of this parlour game was to spin a tennis-ball past one’s opponent who sits at the other end of the table. Suddenly, Bosanquet’s over-the-wrist action had sent the ball bouncing past his amazed adversary, breaking from right to left.

Within a couple of years, Bosanquet was bowling his novel delivery at the nets at Oxford. It amused him, his teammates, and flummoxed visiting batsmen who came down for a hit. But, it was only in the Middlesex-Leicestershire match of 1900 that he finally summoned up the nerve to send one down during an official game.

The fast bowler to spinner

Bosanquet was born in Enfield, Middlesex, to a family of high achievers. His uncle and namesake Bernard Bosanquet was a philosopher and political theorist of note, whose work influenced thinkers like Bertrand Russell, John Dewey and William James. His grandfather, James Whatman Bosanquet, was a banker who also gained renown as a biblical historian. His father, apart from being a successful banker and businessman, was the High Sheriff of Middlesex and captained the Enfield cricket club.

The name Bosanquet was foreign, descended from Huguenot — the roots identical to those of a later practitioner of the googly, Richie Benaud. Indeed, a lot of the suspicion surrounding the delivery stemmed from the exotic sounding name of its inventor.

Proceeding from Eton to Oxford Bosanquet had been an all-rounder, a fast bowler and a batsman. He also excelled in hammer-throwing and billiards. At Eton, he was coached by the famous Surrey professionals Maurice Read and William Brockwell. In 1896, he was selected for the school side against Harrow at Lord’s and scored 120. In his second year at Oxford, 1898, he received his Blue from F. H. E. Cunliffe and played three times against Cambridge. In those days he was a useful bowler, medium to fast, and batted with a free swing of the bat.

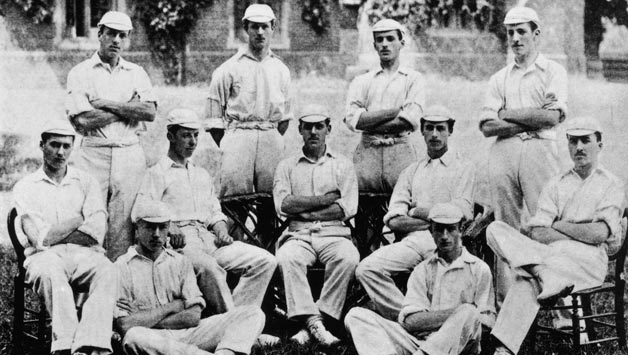

The Eton XI from the 1896 cricket match against Harrow. Standing (from left): Bernard Bosanquet, the Honourable G Ward, Frank Herbert Mitchell, GTL Tryon; Seated (from left): CK Hutchison, Alfred Digby Legard, CT Allen, R Lubbock, Hubert Carlisle Pilkington; On ground (from left): CH Browning, Frank Hubert Hollins © Getty Images

Having grown tired of bowling fast on flat pitches under a merciless sun, Bosanquet opted for the method of walking slowly up to the wicket and gently propelling the ball into the air.

Later he wrote in the 1925 Wisden, “It took any amount of perseverance but for a year or two the results were more than worth it. In addition to adding merriment to the cricketing world, I found that batsmen who used to grin at the sight of me and grasp their bat firmly by the long handle began to show a marked preference for the other end.”

The great Arthur Shrewsbury, unable to read him, started playing everything as an off-break, mumbling darkly to whoever would listen that the googly was unfair. William Gunn was stumped when appreciably nearer the bowler’s wicket than his own.

Wicketkeeper Dick Lilley, who stood in all seven Tests Bosanquet played, proclaimed a little too loudly that he could pick the wrong ’un. In the Gentlemen and Players match at The Oval in 1904: “one of the ‘Pros.’ came in and said, ‘Dick’s in next; he’s calling us a lot of rabbits; says he can see every ball you bowl. Do try and get him and we’ll rag his life out.” Bosanquet bowled two overs of orthodox leg breaks to him, and then changed his body and arm action while sending down yet another leg-break. Confident that this was the deceitful delivery, Lilley expected it to come in to his pads and essayed a delicate leg-glance. The ball hit his off-stump. Yes, apart from the ability to send down the googly, Bosanquet also had guile. “I can still hear the reception he got in the dressing room.”

The googly Down Under

In 1902, the delivery made its first impression on international cricket. Against Australia at Lord’s, Bosanquet opened the bowling for Middlesex and turned one the other way to trap wicketkeeper Jim Kelly leg before. However, Victor Trumper, in his most sublime tour of all, was the next man in and a few crisp strokes ensured in Bosanquet being taken off the attack. But, the world Down Under were soon to be befuddled by this new delivery.

It was during Lord Hawke’s tour to New Zealand in 1902-03 that Bosanquet created sensation and the googly apparently got its name. Three of the matches on the tour were in Australia. In the first Bosanquet bowled all over the place — literally, because Harry Graham had to skip out to point to hit one ball. The next game was at SCG against New South Wales. Victor Trumper was batting on 37 when Bosanquet was put on. Two leg-breaks were played with characteristic ease and beauty of movement into the covers. And then, ‘with a silent prayer’, the googly was floated up. Trumper moved forward with languid ease and the waft of his magical bat. His middle-stump was pegged back. According to AE Knight, in the subsequent Bosanquet-Trumper duels, the batsman often saw the googly coming, but was barely able to cope. The extra pace and bounce induced by the top-spin gave the bowler a supremacy against any but the most skilled batsmen.

The origin of the term ‘googly’ is uncertain. The word was earlier used to describe a high-tossed teasing delivery. Often an ordinary leg-break was referred to this way in Australia. Tom Horan, writing as ‘Felix’ for The Australiasian, suggested that the babyish sound ‘goo’ juxtaposed with’guile’ gave rise to the ‘googly’ used to identify this curious delivery. There is a more romantic version which claims that the term is of Maori origin, stemming from the 1902-03 tour to New Zealand.

The second Australian summer

Whatever be the roots, ‘googly’ came to stay. And Bosanquet was chosen to tour Australia again in 1903-04, as one of the three spinners — Wilfred Rhodes and Len Braund being the other two. His inclusion owed to the influence exerted by skipper Plum Warner, his Middlesex captain. His batting weighed in heavily to argue his case.

His exploits before the Tests was indeed more with the bat, 79 against Victoria and a 99 in a minor match. It was a timely four for 60 against New South Wales that ensured his Test debut at Sydney. The Test, immortalised by Reggie Foster’s 287 and Trumper’s 185 saw him bowl Warwick Armstrong and Syd Gregory with googlies. However, his second innings effort of one for 100 from 23 overs was not considered good enough for his selection for the second Test. Yet, this Sydney match was very significant for the tradition of the googly. Watching Bosanquet in action had been two eager men who would go on to make their names as the foremost exponents of this sort of bowling. In the members’ stand sat Dr Herbert Hordern. And an urchin named Arthur Mailey watched from the Hill.

Back for the third Test at Adelaide, Bosanquet captured three for 95 and four for 73, but Trumper and Gregory hit centuries to take Australia to a 216 run win. After three matches, the series stood 2-1 in favour of the visitors.

Bosanquet hit a quick century against Tasmania but his bowling was quite abominable. Against New South Wales, he scored another hundred, this time in 75 minutes. Yet, his bowling started out as erratic and he might have lost his place in the side yet again had it not been for Dick Lilley. The stumper persuaded Warner to give the wrist spinner another bowl. Bosanquet bowled two batsmen with googlies and finished with six for 45.

In the fourth Test at Sydney, Australia needed 329 to win in the final innings — a tough ask but the pitch was playing well. Bosanquet, wearing a sweater colourful enough to make the Hill occupants call him ‘Elsie’, was brought on to bowl 15 minutes before tea. He had Clem Hill stumped and Gregory leg before almost immediately. After the break, he got rid of Bert Hopkins and Hugh Trumble stumped and Charlie McLeod caught behind. At this stage Bosanquet had five for 12. Finally, he had Kelly caught at slip. It was only some manhandling by fast bowler Tibby Cotter that upset his figures somewhat. Even then 15-1-51-6 was a memorable effort and good enough to seal the Ashes.

The torch bearers

The following summer, Bosanquet achieved his only double of 1,000 runs and 100 wickets. The highlight was the Sheffield match against Yorkshire where his five wickets were accompanied by a sparkling 141. Yet, the most significant games of the season were against South Africa.

Playing for MCC at Lord’s, Bosanquet ran through the visitors with nine for 107. Watching him closely was his acquaintance Reggie Schwarz. A handsome, modest man with a particularly pleasing voice, Schwarz had won three caps as a half back for the England XV and played a while for Middlesex before taking up a position as secretary to the Transvaal financier Sir Abe Bailey. At Lord’s, he was one of the four Springboks to be stumped off Bosanquet.

Three weeks later, Bosanquet came across the South Africans once again while playing for Middlesex. He hit 110 in 85 minutes in the first innings, scored 44 in the second and bowled Louis Tancred and Jimmy Sinclair. Schwarz picked up five for 48 in the second innings and the match ended in a tie. More importantly, googly had found another established practitioner. A few days earlier, after being stumped off Bosanquet, Schwarz had tried his version of googlies against Oxford University, capturing five for 27. Three weeks after the match against Middlesex, he was back at Lord’s, bowling only googlies and top-spinners against an England XI. He took four wickets in each innings, including KS Ranjitsinhji leg before and stumped, and Gilbert Jessop bowled.

By the time England went to South Africa in 1905-06, there were four googly bowlers in the team, Schwarz having taught the art to Aubrey Faulkner, Bertie Vogler and Gordon White. Against their combined skill on the South African matting wickets, England were beaten in four of the five Tests.

The art of the googly had been passed on and the flame would remain burning brightly.

The last hurrah

Bosanquet had one final moment of triumph. Australia visited in 1905, and Bosanquet played the arch-rivals in the first Test at Nottingham. The first innings saw him send down seven erratic overs for 29. However, with Archie MacLaren scoring 140, Australia were left 402 for victory with Trumper unlikely to bat due to a strained back. The situation was ideal for a bowler who might spray the ball everywhere while punctuating the waywardness with some unplayable deliveries. So, Bosanquet was asked to bowl by skipper Stanley Jackson on the third morning.

After a few ordinary overs before lunch, Bosanquet struck after the break. Reggie Duff was caught and bowled. With the score on 75, he began another spell that got him three wickets in four overs. Monty Noble was stumped. Joe Darling bowled and Clem Hill caught and bowled — a high one handed catch which saw the bowler leap up and fall backwards while clutching at the ball. Warwick Armstrong was caught by Jackson at cover. It was 100 for five and all five had gone to Bosanquet.

Tibby Cotter once again hit him around, but Wilfred Rhodes got rid of his strong-arm tactics. Bosanquet had Syd Gregory caught at mid-on as he tried to hit him out of the attack. Frank Laver tried to sweep, hiding the ball from view of the wicketkeeper, but Dick Lilley, ever alert, spotted the missed delivery and whipped off the bails in an inspired piece of stumping. Charlie McLeod, desisted by captain Darling from saving the match by appealing against the light, was trapped plumb. With Trumper not being able to go past the gate in his pain, Australia were all out for 188. Bosanquet had eight for 107 from 32.4 overs. It was one of the greatest Ashes bowling performances.

He had yet another stupendous match right after this Test. Against Sussex at Lord’s, he hit 103 at a run a minute and 100 in an hour and a quarter, besides taking three for 75 and eight for 53.

Yet, it was the last hurrah for Bosanquet the bowler. He was not used in the rain affected second Test at Lord’s and bowled 19 overs at Headingley, picking up one wicket for 65. Wisden wrote: “Bosanquet was a complete disappointment.” The bowler himself was not very amused by the press reports. It was as much due to the criticism as his own loss of bowling form that he lost his knack of taking wickets.

Down the years, he was to make a lot of runs for Middlesex, even a mind-boggling 25-minute century for Uxbridge against MCC in 1908. But, his days as a bowler were over.

Bosanquet finished with 25 wickets in seven Tests at 24.16. He did not really hit it off as a batsman at the highest level. In First-Class cricket, however, his batting and bowling were often equally brilliant. He amassed 11,696 runs at 33.41 with 21 centuries while capturing 629 wickets at 23.80 with 45 five-fors and 11 ten-wicket hauls.

Years after his retirement, Bosanquet wrote an article in The Morning Post titled ‘The Scapegoat of Cricket’. It was reproduced in the 1925 issue of Wisden. His piece ran: “Poor old googly! It has been subjected to ridicule, abuse, contempt, incredulity, and survived them all. Deficiencies existing at the present day are attributed to the influence of the googly. If the standard of bowling falls off it is because too many cricketers devote their time to trying to master it… If batsmen display a marked inability to hit the ball on the off-side or anywhere in front of the wicket and stand in apologetic attitudes before the wicket, it is said that the googly has made it impossible for them to attempt the old aggressive attitude and make the scoring strokes.

“But, after all, what is the googly? It is merely a ball with an ordinary break produced by an extra-ordinary method. It is not difficult to detect, and, once detected, there is no reason why it should not be treated as an ordinary break-back. However, it is not for me to defend it. If I appear too much in the role of the proud parent I ask forgiveness.”

Bosanquet passed away in 1936, at Wykehurst Farm, Ewhurst, Surrey, a day before his 59th birthday.The family vault in Enfield Cemetery bears no identification of him as the inventor of googly. According to David Frith, the inscription adorning his grave should have read, “He is the worst length bowler in England and yet he is the only bowler the Australians fear.”