Brian Statham, born June 17, 1930, was one of the greatest fast bowlers produced by England, and the holder of the world record for Test wickets for a short period of time. Arunabha Sengupta remembers the life and career of the man who was perhaps one of the most universally loved characters in the game.

Manchester, 1968. Late in the cricket season. A car speeding along Cheetham Hill Road was being tailed by a police car. The law finally drew level and the vehicle was waved down by a uniformed arm. At the kerbside, an officer of the Lancashire Constabulary asked for the license of the errant driver.

The name on the document read ‘Frank Tyson’.

The questions followed thick and fast.

“Are you Frank Tyson, the former England fast bowler?”

“Yes, I am.”

“Are you on your way to a fire burning your house down?”

“No, I’m not.”

“On your way to the hospital for the impending arrival of your first-born perhaps?”

“No.”

“Do you realise sir that you were going almost as fast as you used to bowl?”

“Yes, I do.”

“And what might be the reason for that, sir?”

“I’m late for an official function at Old Trafford to mark the retirement of my former fast-bowling partner.”

“Would that be Mr. Brian Statham, sir?”

“Yes, he is retiring from First-Class cricket at the end of the season.”

“He is a very important person sir, and if you want to salute him on the occasion, please make sure you get there safely.”

The policeman waved the former England pace bowler off with a warning.

Fast but pleasant

It was not just the Lancashire Police who displayed overwhelming admiration for Brian Statham. Incredibly for someone who rose to fame as a fast bowler, there was hardly a soul in the cricketing world or elsewhere who had anything but the utmost respect for this honest, toiling bowler who served England and Lancashire for many a year.

There was indeed little to dislike in Statham. Long, lean and laconic, he was a workhorse almost all through his career. He bowled fast — make no mistake about it. With time he worked on his speed, developing into one of the fastest of his era. He was as competitive as the next man. Yet, intimidation was not his way. Nor the theatrics associated with nasty, fast men.

When a vicious break-back off his very first delivery to Colin McDonald in the Adelaide Test of 1959 cut back from outside the off-stump and removed the varnish off the bails without dislodging it, all Statham did was to raise his eyes and have a quiet word of dissent with the Cricketing Almighty. Only one cricketing occurrence could make his expressions go on overdrive — when a straight ball made it past his own left-handed, primitive, tail-ender’s defence and rattled his own stumps. Then he would stare disbelievingly at the spot the ball had pitched, wondering how much deviation it must have to go past his defence.

Throughout his career, he remained a Nice Guy. Even Lancashire county authorities relented in their rather austere unwritten rules and made a fast bowler the captain of the side, because his name was Brian Statham.

His style depended little on digging the ball into the pitch and making it rear up at the batsman’s chin. Almost always he was more of a ‘ducks and drakes’ paceman who skidded through, much like a flat stone across the surface of a pond. His balls were much more likely to do damage to the toes than the head. And never did he bounce a tail-ender, no matter how extenuating the circumstances.

During the Port-of-Spain Test of 1953, West Indian paceman Frank King split the eyebrow of Jim Laker with a largely unnecessary bouncer. In a subsequent match, Statham found King facing him and his partner in crime, Fred Trueman, urging him to let King ‘have one’. Statham disagreed, “Nay, I think I’ll try to bowl him out.”

The better batsmen did receive occasional short ones that passed disconcertingly close to their noses. Statham was seldom overjoyed by the intimidation. It was an important part of his artillery and that was all there was to it. When Waddie Reynolds, the Northants opening batsman, was hit by one of his shorter ones that reared off the grassy Old Trafford wicket, he fell like a hacked log. No one in the ground was more concerned than Statham who seriously believed that he had killed him. And when Reynolds did recover, no one was more relieved.

Running into the wind

However, the methods of Statham were driven more by practical than emotional considerations. He preferred to take wickets, and pitching the ball up seemed to get him more. The man himself was of solid working-class stock, who loved his beer and could not quite fathom the intricacies of champagne: he called it ‘soady pop’ when forced sip some after bowling England to Test victories. Similar to his straight, honest enjoyment of life and absolute lack of pretentiousness was his fast bowling strategy: “If tha’ bowls all of tha’ balls on the off stump, tha’ has to have all of tha’ fieldsmen on the off side. And if tha’ bowls on the leg stump, tha’ needs all of tha’ fieldsmen on the leg side. Me, I just bowl straight and then I doan’t need any fieldsman!”

He was famed for his accuracy and dead-on-ball. According to Godfrey Evans, who crouched behind the stumps to his offerings for years, one could always tell that ‘George’ was going to have an off day whenever one ball in the first over was more than six inches wide of the wicket. If a batsman received a half-volley, Evans used to go up and congratulate him for what was bound to be the only piece of fortune he would get from Statham that day. Statham seemed to be disconcerted only when the ball swung a long way. Controlling movement through the air was not really one of his strong points.

His unerring accuracy and indefatigable capacity of bowling long spells was combined with his pairing with Fred Trueman and Frank Tyson, two of the fastest ever produced by England. This resulted in many, many matches when Statham ran in again and again, bowling into the wind, blocking one end, as his partner made merry at the other. Batsmen, driven to desperation by their inability to score off Statham, took risks and succumbed to the others.

When Tyson took six wickets at Sydney in 1954-55 to bring England a famous 38-run win, he was obviously the hero. However, at the other end, Statham had sent down 19 eight-ball overs to capture three for 45. In Tyson’s words, “The glamour of success was undoubtedly mine. When in the second innings of the Sydney Test I captured six for 85, few spared a thought for Statham who on that day bowled unremittingly for two hours into a stiff breeze and took three for 45… I owed much to the desperation injected into the batsmen’s methods by Statham’s relentless pursuit. To me it felt like having Menuhin play second fiddle to my lead.”

Neville Cardus dubbed this statement as the most generous tribute ever paid by one cricketer to another since Archie MacLaren’s famed comment that by the side of Victor Trumper he was like a cab-horse next to a thoroughbred Derby winner. Statham, characteristically, was less sophisticated in describing his methods. According to Cardus again, he summed up his bowling in the match as: “When I bat and miss, I’m usually out. When I bowl and they miss — they’re usually out.”

Slow road to the fast bowling peak

Much of his cricket was without pretence, as was much of his way up to the top level. Born in Gorton, Manchester, his progress was slow and steady, from Whitworth School first XI to the Denton West club in the North Western League, and to Central Lancashire League for Stockport. It was a difficult terrain, full of international dazzle of men like Cec Pepper, George Tribe, Jock Livingston, Vijay Hazare and Vinoo Mankad, which often outshone Statham’s fresh northern light. He also played football for Denton West as left wing, and was offered trials with Liverpool and Manchester City. However, it did not work out as his father did not want him to pursue football as a career.

It was during his national service in the Royal Air Force that the amateur talent scout Corporal Lazarus was impressed by his potential at the Stafford base. He wrote to the MCC about Statham and they in turn advised the paceman to go for a trial at the Lancashire County Club.

He made his debut for Lancashire soon enough, but his open chested action did not really delight the purists. However, with the retirement of Dick Pollard, there was little choice available in the speed department to the county men. He was re-christened ‘George’, because after many, many years the county was without a player by that name. And Statham liked it. It was straightforward and uncomplicated, much like the man. Although with time cricket writers would draw on his spare frame and speedy approach to brand him ‘Greyhound’ and ‘Whippet’, ‘George’ stuck and friends in the county circuit always referred to him by this simple forename.

Although several voices doubted his credentials, in the Roses match of 1950 his pace and accuracy impressed England’s premier opening batsman Len Hutton. Statham took the first three Yorkshire wickets for 13, before ending with five for 32. With injury plaguing the England side during the New Zealand leg of their tour in 1950-51, Hutton advised captain Freddie Brown to summon this young Lancashire bowler. Thus he travelled, alongside another reinforcement in the form of Roy Tattersall, and made his debut against New Zealand at Christchurch, claiming Bert Sutcliffe as his first wicket.

The first few years saw him less than a certainty in the Test side, with Alec Bedser being the primary choice as fast bowler. However, some excellent bowling on the placid wickets of West Indies under Len Hutton’s leadership made his claims stronger. In the third Test at Georgetown, he dismissed Frank Worrell, Jeff Stollmeyer and Clyde Walcott for 10 runs, and it proved crucial to England’s victory by nine wickets. Following this, he soon became an important part of skipper Hutton’s pace machinery that ultimately blew Australia away in 1954-55.

The greatest hits

For most of his career, and especially in the Ashes encounters, Statham bowled as support for Trueman and Tyson. However, he himself could well qualify as express. It was against the South Africans that he produced some of his best bowling performances. At Lord’s in 1955, the visitors needed just 183 for win. And Statham ran in untiringly for a couple of hours, pitched the ball on the seam and used the uneven pitch to perfection, taking seven for 39, earning England a 79-run win. Five years later, on the same ground, against the same opposition, he took eleven for 97, his only 10-wicket haul in Tests. England triumphed by an innings, but the match is remembered more due to umpire Frank Lee calling Geoff Griffin for throwing.

The 1959-60 tour of Australia was disastrous for England, but Statham bowled beautifully throughout. At Melbourne, in the second Test, he slogged away with supreme commitment, taking seven for 57 from 28 overs, restricting the young Australian side to a lead of 49. It is largely considered to be one of the best spells on the ground. However, within two hours he was bowling again as the Australians cruised to victory. Against the left-handed pace of Alan Davidson and Ian Meckiff, the English batsmen had collapsed for 87. It was perhaps the only time in his career that Statham gave vent to his emotions, letting the batsmen know exactly what he thought of their efforts.

By the late fifties, Statham also combined with Ken Higgs to forge a formidable fast bowling partnership for Lancashire. For much of his career he had been the lone crusader with the ball for the county. During the subsequent period captured wickets by the bushel in the championships, and even in the Test matches, against South Africa, West Indies and Australia. The period of late fifties to early sixties saw some of the most memorable performances.

At Manchester in 1961, he claimed five first innings wickets, bringing Australia down to the knees , ensuring a huge first innings lead for England. However, the Test match took a dramatic turn with Davidson hammering the English attack and then Richie Benaud turned the ball from round the wicket. It ended with the trademark befuddlement of Statham, with Davidson’s full pitched delivery flattening his stumps, leaving him wondering again about the mystery of a ball getting past his rustic willow.

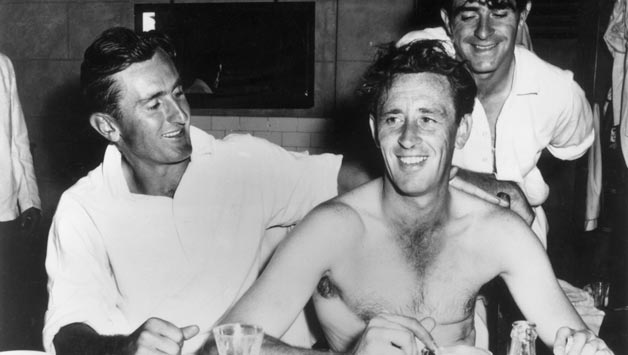

A shirtless Brian Statham congratuated by Ted Dexter (left) and Fred Trueman in the England dressing room in 1963 after he broke the world record to become the highest wicket taker in Tests © Getty Images

World record and last days

When England embarked on the Ashes tour of 1962-63, Statham was past his prime, but there was a landmark in the offing. He was on 229 wickets, poised to overtake the world-record tally of 237 set by assistant manager Alec Bedser. Close behind, Trueman was on 216 and Australian captain Richie Benaud on 219. Statham did not do too much on the tour, but managed to get there first when in the Fourth Test at Adelaide. It was Trueman who caught Barry Shepherd in the gully off his bowling to give him the record. After the series, he returned to England while Trueman continued to play the Tests in New Zealand. There the Yorkshireman broke Statham’s record after only two months.

With his peak form deserting him, Statham lost his place in the English side during the home series against West Indies in1963. In a slightly debatable decision, 39-year-old Derek Shackleton was preferred in his place. He did come back for one last romp in 1965 at The Oval, against his favourite opponents the South Africans. He showed glimpses of his old self once again, capturing five wickets in the first innings. He might have been selected to tour Australia based on this performance had he not declared his unavailability.

Statham retired from First-Class cricket after the 1968. In his last First-Class match, played against traditional rivals Yorkshire, he captured six for 34 in the first innings.

His final record shows 252 wickets at 24.84 apiece from 70 Tests, putting him at par with the greatest fast bowlers of all time. Even taking into account the grassy Old Trafford track that did aid him considerably, his 2260 wickets in First-Class cricket came at a remarkable average of16.37 — the best among bowlers with more than 2000 wickets since the beginning of the 20th century.

The method and the man

Statham stood at six feet, lean and spare in spite of his fondness for beer. He ran in tirelessly even though he gave up smoking only after he gave up cricket. His run up consisted of 17 paces, all the while leaning forward and gliding over the distance with a fluid motion. As he delivered, he would be open at the shoulders, his eyes looking the batsman over the unorthodox side of his leading arms. His hips and crossed legs would assume the classical closed position. It lent credence to his incredible flexibility. His legs preceded his body into the final step, at an impossibly acute angle and often his right boot would land on the side of the sole where there were no studs to prevent him from slipping heavily. The arms performed a curious routine — the left pointed up while his right circled as if from 11 o’clock back to 11 o’clock on the face of a clock. Statham was double jointed at his shoulders and elbows. One of the tricks that astounded onlookers was his removing his cricket sweater by reaching over his left shoulder with his right arm, grasping the hem and pulling it over the head. Hence, the bowling arm bent beyond 180 degrees at the elbow, a sort of chucking action in the other way.

He did not swing the ball much, but was the master of the breakback — in the tradition of Tom Richardson. It would cut into the batsman from wide outside the off-stump even on the most placid of wickets. According to Tyson, “He bowled it by placing the first two fingers of his hand on one side of the vertical seam, with the remaining fingers spread and tensed on the opposite side of the ball. At the moment of release, he snapped the index and second finger from off to leg, imparting a vicious cut.”

Alongside his bowling, he was a superb out-fielder with fast accurate throws and safe hands.

Statham himself was aware of his weaknesses more than anyone else. He confessed to his smoking too much, admitting that he breakfasted on ‘a fag, a cough and a cup of coffee.’ Right through his career, he suffered from a big toe that lost its nail often due to the pounding it took in the delivery stride. During his playing days, one could often witness Statham walking back to his bowling mark with a bloody sock protruding from a hole in his left boot, snipped to relieve the pressure on the raw toe. During tea intervals of Test matches, teammates witnessed Statham, stripped to the waist, removing his boots, peeling off his socks, placing his feet on a chair and talking to them: “Come on lads, tha’s only got another two hours to go and then tha’ can have a good soak and a neet’s rest.”

He was a popular man. And he lived a hard life. He served on the Lancashire committee after his retirement, from 1970 to 1995. However, personally he was hard up. In 1989, Trueman learned of his long lasting financial difficulties and organised two testimonial dinners to raise money for his bowling partner. It did help him for a while, but not for long. The last days of life were full of pain. Statham passed away in 2000 after suffering from leukemia.

The long Warwick Road runs through Manchester past the Old Trafford Cricket Ground. The section next to the cricket ground has been renamed Brian Statham Way.

The attitude of Statham’s fast bowling is recounted vividly by Peter May. In his autobiography, AGame Enjoyed, the former England captain remembered the untiring service he provided without a hint of malicious intention.

“It never mattered what you asked him to do, whether it was to come on for a few overs, to bowl until lunch, to bowl uphill or upwind. Whatever it was, he would take the ball and do it. Once at Old Trafford he brought a ball back to hit me inside the right thigh where there was no protection. The pain went right through me. It was the last ball of an over, and I stood there determined not to show that I had been hurt. Then I noticed ‘George’ half down the pitch, hands on hips, looking at me with a half-smile. ‘Go on, skipper, rub it.’ he said, ‘I know it hurts.’ There was a touch of sympathy in it. He bowled without a trace of animosity.”