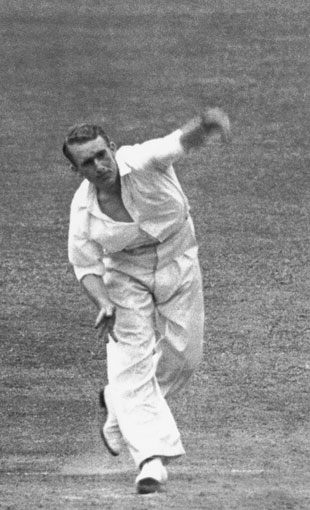

Johnny Wardle (born January 8, 1923) took 102 wickets in 28 Tests at an average and economy rate that rank among the best of all time. Arunabha Sengupta looks back at the man whose circumstances and attitude prevented him from achieving much more in his career.

When Ray Lindwall’s express delivery thudded into the thigh of the English tail-ender, a simultaneous gasp was heard around the stadium. The thousands gathered at Lord’s feared for the gutsy man at the wicket, who had boldly flailed the Australian pace – mostly off the edge of his willow. However, soon the collective concern was converted into peals of laughter as the man in question, hit resoundingly on the thigh, immediately began to rub his elbow. And when a flourishing cover drive soared over the slips for four, the same man grabbed an imaginary piece of chalk and rubbed his bat with a curious sense of purpose.

Indeed, without this ability to laugh at whatever fortune flung his way, often the chuckles of mirth aimed at himself, Johnny Wardle would have had a difficult time withstanding the cruel lashes of fate.

He was a canny left-arm spinner, perhaps the most innovative to bowl for England. He could propel them out from the back of his hand, with a Chinaman good enough to flummox the best, but most often stuck to the orthodox slow left arm stuff preferred by Yorkshire and England. Either way, he did a fabulous job.

Yet, his unfortunate career coincided with that of the more aggressive, and the more frequently favoured, left-arm spinner Tony Lock. It did not suit him well that England’s No 1 spinner of that era, Jim Laker, accepted Lock as his spin-twin, and bowled in tandem with him for Surrey.

Spinner, rebel and prankster

There were other reasons why Johnny Wardle did not play too many Tests in spite of boasting a record better than Laker, Lock and most other spinners across eras. During a post-War era that stuck to convention and frowned upon the radical, Wardle was a confirmed maverick. Fred Trueman was another Yorkshireman who did not exactly toe the orthodox lines, and before the swinging sixties started to accept him as an icon, he too lost out on about fifty or so Test matches. Wardle paid a heavier price.

He dared to bowl Chinamen when left-arm spinners were supposed to tweak them with their fingers. At Durban in 1957, when England needed a victory to clinch the series in the third Test match, captain Peter May asked him to bowl orthodox left-arm spin. Wardle rebelled and bowled the dangerous Roy Mclean with a deceptive googly that came out from the back of his hand. When he informed May how he had got his man, the captain sternly repeated his instruction.

Wardle was also a joker, who needled the high and mighty. Once, on taking a blinder from the bat of Cyril Washbrook, he did not celebrate, and the batsman kept shuttling between the wickets, unaware that he was dismissed. “He hit the ball like a shell. It went straight to me, one hand, and I caught it. Washie was running for two, possibly three. He was proper upset and disgusted was Washie, because I’d make him look so silly,” Wardle recalled later. Washbrook served as a selector during the mid-1950s, and Wardle did not really gain too much by making him look silly.

According to his biographer Alan Hill, his penchant for clowning “masked his distress at the lack of appreciation of his talents… he was devalued as a bowler and as the heir to Hedley Verity and Wilfred Rhodes”.

And finally, when Ronnie Burnett was made the captain of Yorkshire ahead of him, Wardle wrote a series of articles for the Daily Mail criticising the county and its new skipper. Wardle had just come back from South Africa with 26 wickets at 13.81. But he played just one more Test. Following his newspaper articles, his invitation to tour Australia was withdrawn.

Hence, Wardle ended up playing only 28 Tests for England over nine years.

Even in these Tests, he was often restrained from achieving what he could. On his debut, in 1948, Gubby Allen allowed him only three overs as West Indies piled up 497. His response was to keep taking wickets, 148 in the English summer of 1948, more than 100 in each of the next nine seasons. With Trueman and Bob Appleyard, Wardle formed a bowling combination for Yorkshire seldom encountered in First-Class cricket.

At the international level, in spite of the few opportunities, he demonstrated what he could achieve given a long run. In 1953, he took four for 7 against Australia at Old Trafford, and the next year captured seven for 56 against Pakistan at The Oval. It was a pity that he did not go to Australia in 1958-59. Four years earlier, when he had made the trip, he had practiced his back of the hand deliveries on the deck of Orsova and had managed quite a bit of success on a pace dominated tour.

The England cricket team aboard the liner Orsova on September 16, 1954 (Back row, from left): George Duckworth, Tom Graveney, Peter May, Len Hutton, WJ Edrich, Lord Cobham, Bob Appleyard, HS Altham, RT Simpson, JV Wilson, Alec Bedser, CG Howard, Trevor Bailey, Godfrey Evans. Front row (from left): J McConnon, JB Statham, Johnny Wardle, Keith Andrew and Colin Cowdrey © Getty Images

In the end, his career haul of 102 wickets in 28 Tests at 20.39 stands out as both extraordinary and incredulous. More than underlining his claims as one of the greats of slow bowling, it emphasises the curious selection policies of England in the 1950s.

Among all the bowlers to have captured 100 or more wickets in Tests, only six have a lower average than Wardle. All those six played before the First World War, when wickets were unpredictable and batting much more of a game of chance.

And when it comes to consistent showing at home and abroad, Wardle stands quite some distance above the other great spinners of his land, including Laker, Tony Lock, Hedley Verity, Derek Underwood and Graeme Swann.

Only three bowlers with over hundred wickets ended with a better economy rate. Wardle was often a joker on the field, but he played hard and did not give an inch.

Four months after Laker picked up his famous haul of 19 for 90 at Manchester, Wardle bowled alongside him at Cape Town. Laker finished with three for 72 in 42.1 eight ball overs. Wardle bowled five more balls, and took twelve wickets for 89.

A look at the tables that follow will perhaps underline how cruelly Wardle’s career was cut short and what he might have achieved given a longer run.