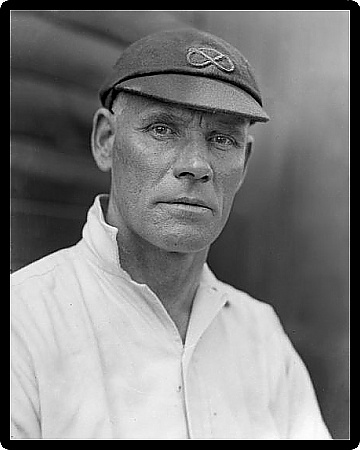

Sydney Barnes born April 19, 1873, was perhaps the best ever bowler in cricket. Arunabha Sengupta looks back at the career of the man who took 189 wickets at 16.43 in 27 Tests.

That final series

On March 3, 1914, Major Booth and Albert Relf picked up the remaining South African wickets at Port Elizabeth, following which Jack Hobbs and Wilfred Rhodes rattled off the winning runs. England took the five match series 4-0.

Less than four months later, 20-year old Gavrilo Princip walked out of Schiller’s Delicatessen in Sarajevo and fired two shots into the open car of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne. The sparks of the First World War were kindled and there would be no Test cricket for the next seven years.

Sydney Barnes did not play in the match at Port Elizabeth. The authorities were not willing to pay for his wife’s accommodation. Barnes, never one to compromise on such matters, put his foot down. As a result, he played only four Tests in the series and that was to be the end of his Test career.

In those four Tests, Barnes had scalped a whopping 49 wickets at 10.93 apiece. It remains a world record after almost a 100 years. Jim Laker came closest, with 46 in his famed 1956 summer, but played a Test more for his wickets.

The eight innings Barnes bowled in the series saw him pick up seven five-fors. His only ‘failure’ was three for 26 from 16 overs in the third Test. In the four Tests, he took 10 or more wickets three times, missing out in the third Test with eight.

In the second Test at Johannesburg, Barnes took 17 for 159, a record that stood till Jim Laker rewrote it with his 19 at Old Trafford. In his final Test, at Durban, Barnes got seven in each innings.

Virtually unplayable on the matting wickets of the country, only Herbie Taylor, that early Springbok batting great, had managed to counter him with a semblance of confidence. By the time the fourth Test took place, Barnes was sure that he had the measure of Taylor. In the second innings, Taylor resisted, while Barnes bowled on and on, pegging away at some slight weakness apparent only to his keen bowler’s eye. Barnes finally got him leg-before for 93, as he had maintained that he would. It was the fifth time out of eight innings that he had dismissed the South African captain. He finished his final bowl in Tests with seven for 88 from 32 overs. On the field were Hobbs and Rhodes, and they agreed that it was the finest they had seen Barnes bowl.

That is saying something, given that both Hobbs and Rhodes had been present two years earlier at Melbourne, when Barnes had opened the bowling with Frank Foster on the first morning. He had bowled William Bardsley with his first ball, trapped Charles Kelleway leg before, castled Clem Hill and had Warwick Armstrong caught by his old Warwickshire wicketkeeper Tiger Smith. Seven supreme overs had seen him captured four wickets for one run, four batsmen of fearsome repute, the best batting line up of the day. The great Clem Hill had later recounted his dismissal: “The ball pitched outside my leg-stump, safe to the push off my pads, I thought. Before I could pick up my bat, my off-stump was knocked silly.” Barnes apparently got those wickets to show captain Johnny Douglas that it was he who was the right man to share the new ball with Frank Foster, not the skipper.

No argument

It might be difficult to agree about Barnes was bowling at his best. After all, there is little to choose between a continuous sequence of surreal performances that resulted in an ultimate tally of 189 wickets in 27 Tests at 16.43. Of course, his genius went far beyond the international career. Fourteen years after he had played his last Test, in the summer of 1928, the West Indians visited England. Barnes turned up for Wales at the Llandudno Oval, at the age of 55, capturing seven for 51 and five for 67. A year later, he captured six for 28 and four for 62 for Wales and eight for 41and one for 19 for Minor Counties in two matches against the visiting South Africans. At 56, he was the fifth in the year’s bowling averages. In 1938 he was 65, beyond the retirement age in most jobs around the world — most of all active sports. That was his last season as a League professional and he scalped 126 wickets at 6.94.

It would be far easier to agree that Barnes was the most difficult bowler to face — of his times and beyond. Every opponent, however partisan or lacking in grace, agreed to his absolute supremacy with the ball. No bowler in history has had such universal repute as the greatest. Even in 1930, the batsmen who faced him came away shaking their heads in disbelief.

Standing over six feet, broad of shoulders and deep of chest, with endless arms and sturdy legs, he supposedly had perfect build for a bowler. He was never coached, and was by no means born into the game. Perhaps that is why Barnes became a self-made bowler, of a kind that is difficult to classify.

We can try to call him right-arm fast-medium — that indeed was his pace. But, the balls carried with them the accuracy, spin and resource of a slow bowler. He released from high, and got uneasy lift from the pitch, rapping many a painful knuckle and making many of the worthiest batsmen hop.

He was reasonably quick, often compared to Alec Bedser in terms of pace. And then he had a faster ball — and, of course, a slower one, both cunningly concealed. He could also bowl yorkers with precision and venom. Yet, strangely he considered himself a spinner — all the tricks were supposedly performed with his fingers. He moved the ball in the air, both ways and often late, but claimed never to have resorted tothe technique of bowling seam-up. Additionally, he could bowl both off-break and leg-break, with the slight manoeuvring of the first and second fingers. He could bowl the googly too, although Neville Cardus claims he admitted that he didn’t (I didn’t need one, he is supposed to have said). When the occasion or the wicket demanded, he could be a slow bowler — and perhaps the most difficult in the world.

And finally there was hostility and stamina, laced with the strategic acumen for probing at the weakness of the batsman for hours, weaving a web of confusion with each ball, till the man was trapped and overcome.

Often lesser batsman could not even edge a catch. Hence was born the classic Sydney Barnes story, of the occasion when two tailenders played, missed and, once in a while snicked, without managing to be dismissed. Barnes stalked away at the end of the over grumbling: “They aren’t batting well enough to get out.”

You’re coming to Australia with me

Barnes entered the scene as a 19-year-old fast bowler, given a go by Warwickshire in a two-day match against the strong Minor County side of Cheshire. The initiation ended wicketless. His appearances for Warwickshire remained few, far between and largely fruitless. A professional in need for money, he went into League cricket with Rishton from 1895 to 1899 and then for two seasons with Burnley. He was virtually unknown, having turned out only twice for Lancashire, when England captain Archie MacLaren faced him in the nets in 1901.

By then Barnes had become much more than a fast bowler, with all the devious deceptions nurtured to perfection and kept for easy retrieval up his sleeve. The Cardus version of the episode runs thus:

AC MacLaren, hearing of his skill, invited him to the nets at Old Trafford. “He thumped me on the left thigh. He hit my gloves from a length. He actually said, ‘Sorry, sir!’ and I said, ‘Don’t be sorry, Barnes. You’re coming to Australia with me.’ ” MacLaren on the strength of a net practice with Barnes chose him for his England team in Australia of 1901-02.

Peeling off the Cardusian flavour of fantasy, we realise that the session did get Barnes into the Lancashire team. It was for the last match of the season against Leicestershire at Old Trafford. Rain washed out the first day, but in the first innings Barnes took six for 70. MacLaren announced after the match that this unknown bowler – with a First-Class record of 13 wickets spread across seven seasons — would be in his team to Australia.

On the way to Australia, the acerbic personality of Barnes rubbed many a teammate the wrong ways. When a raging storm made the seas well up ominously, MacLaren famously comforted one of his men with the words: “If we go down, at least that bugger Barnes will go down with us.” However, his worth with the ball far outweighed his quirks of personality.

Many a bowler bit the dust on the true Australian tracks of the day. For Barnes, however, the sun drenched land was closest to bowling heaven. He began with five wickets against South Australia, twelve against Victoria and five against New South Wales.

The batting of the Australian side comprised of Victor Trumper, Joe Darling, Clem Hill, Monty Noble, Syd Gregory and Reggie Duff. On his Test debut at Sydney, Barnes picked five for 65, and one for 74. In the second Test at Melbourne, he got six for 42 and seven for 121. In the next match, he broke down with a knee injury and did not bowl any more on the tour, but his reputation had been made.

The professional

Following this, the career of Barnes followed an unusual path. During 1902 and 1903, he turned out for Lancashire, bowling his heart, soul and shoulders out. Yet, at the end of the 1903 season, he left the club after a dispute about winter employment. For the rest of his career, he played professional League cricket, turning out once in a while for Staffordshire and in the Minor Counties competition. Every league club that ever engaged his services won the competition.

Throughout his playing days, he never compromised on the pay cheque for his labours; but he was too great a craftsman to compromise on quality even on purpose when embittered by financial disagreements.

Barnes bowled only in the famous 1902 series, picking up six for 49 and one for 50. And then he did not play the rest of the matches even as England lost the Ashes with the three run defeat at Manchester. What would have transpired if he had been there to bowl his curious mixture of pace and spin? One can only conjecture. In fact, he never played for England again till 1907. He did not tour Australia with Plum Warner’s men, nor did he take part in the 1905 Ashes.

According to Cardus his omission was due to the problems that he brought with his oodles of talent. “He was in those days not an easy man to handle on the field of play. There was a Mephistophelian aspect about him. He didn’t play cricket out of any green field starry-eyed idealism. He rightly considered that his talents were worth estimating in cash values.”

It does the bowler immense credit that the incorrigible romantic in Cardus could not help but be snared by his genius, dipping his pen in loftiest praise while chronicling the deeds of the penny counting professional. He included Barnes in his six cricketers of the Wisden century, the others being Don Bradman, WG Grace, Jack Hobbs, Tom Richardson and Victor Trumper.

He returned to the Test fold in December 1907, in Australia. England lost the series 1-4, but Barnes picked up 24 wickets. And at Melbourne, he enjoyed his great moment of glory. He captured five for 72 in the second innings as Australia set a target of 282. And with the ninth wicket down at 243, he scored an unbeaten 38, adding 39 with last man Arthur Fielder, squeezing a win by one wicket, the only English victory of the series. Indeed, it is said that he could have been a very good batsman if some important people, like MacLaren, had not advised him to ignore batting, so desperate had they been to have him bowling at his best.

After 17 Ashes wickets in the summer of 1909, he returned to his favoured land Down Under in 1911. The tour is remembered as the blueprint scripted by Frank Foster’s pace, line and field for the future development of Bodyline. However, Barnes captured 34 wickets to Foster’s 32, even though he was often plagued in those days by bouts of rheumatism.

In the experimental triangular Test series that followed, Barnes picked up 39 wickets at 10.35. This included 34 at 8.29 with five five-wicket hauls and three 10-fors against South Africa in three Tests.

At the end of his career, the figures he boasted were nothing short of miraculous. The South Africans suffered miserably against his genius, losing five or more men to him in 12 of the 14 innings they batted against him, and ten or more wickets in six of the seven Tests. But, the more established Australians did not do much better either, even in their own backyard.

His proud pursuit for the highest professional remuneration kept him from playing too many First-class matches. But, his overall collection of wickets remains eye-popping. Leslie Duckworth, in S. F. Barnes — Master Bowler, provided the break-up of his 6229 wickets in all forms of the game, at an average of 8.33

No batsman ever mastered him. When asked which of them he found most difficult he used to answer: “Victor Trumper”. When asked who next, the retort would be: “No one else ever troubled me.”

What made him such a supreme exponent of his craft? We may never know the secret.

Only a faint clue is provided in the tips Barnes passed on many years later to the South African off-spinner Hugh Tayfield, “Don’t take any notice of anything anybody ever tells you!”