by Arunabha Sengupta

Trent Bridge, 1965. A Test that will forever be special in the history of South African cricket.

On a grey and grassless pitch, with the sun out, the visitors are happy to win the toss and bat. But by the time the score pushes along to 40, four men are out. Tom Cartwright makes the ball do all sorts of things. At 80 Bacher loses his stump to Snow.

Peter Pollock cannot bear to watch his brother defy the bowlers in these circumstances. Every ball is filled to the brim with tension. He locks himself up in the backroom as van der Merwe joins Graeme.

What follows is a masterclass of counterattack. Pollock, according to his brother Peter, “[takes] the English attack in his teeth and shakes it like a dog would do with a rag doll.” As he starts scoring runs, his brother is locked away by his mates. He cannot be allowed to watch. Too much is at stake.

Graeme pierces the field with elan and class and finds gaps that mortals cannot see. 21 fours in his 125, the last 91 runs off 90 balls in 70 minutes during which van der Merwe scores 10—a knock that makes him a bona fide legend. When Peter is allowed to come back and watch, he sees his brother being caught in the slips.

The total is 269. Now Peter Pollock strikes twice before the day is over. The victims are on the wish list of every bowler. Boycott edges to slip and Tiger Lance juggles the ball for a few excruciating fractions of a second before clutching on. Barrington has his stumps uprooted. England are 16 for 2. It is also the birthday of the mother of Graeme and Peter.

But in the end, only 29 separate the sides even though Peter has five wickets in the first innings.

In the second knock, Bacher, Barlow, Graeme Pollock all get half-centuries. 2 for 35, 4 for 193, 7 for 243 … the score looks alternately good and bad. The final total is 289. 319 to win.

Once again England start towards the end of the day. Peter Pollock induces an edge off Barber. Titmus is sent in to hold fort and is out soon after.

Snow, sent in as the second nightwatchman, is out early the following morning. The score reads 10 for 3. Barrington gloves a hook off Pollock, and it is 13 for 4. At 41 Cowdrey raises his heel a wee bit as he misses a leg-glance off McKinnon and Lindsay stumps him in a flash. At 59 Boycott succumbs to McKinnon’s break.

55 runs between Smith and Parfitt and then Graeme Pollock the bowler strikes. The leg break catches the England captain plumb.

But Parfitt-Parks, the last pair that can bat, put together a fighting, frustrating partnership. The score crosses 200.

Peter Pollock, for the first time in his life, summons God to help him. If he gets the three wickets, he prays, he won’t touch the celebratory drink.

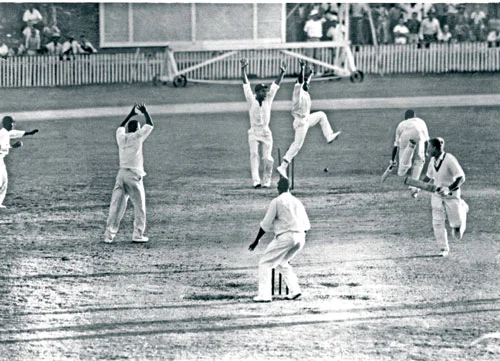

And his prayers are answered. Parfitt and Cartwright fall at 207. At 224 Larter skies one and it is swallowed by the bucket hands of van der Merwe.

This is the proudest moment in the lives of the Pollocks—Graeme the gem in the first innings and Peter picking up 10 wickets in the match. Now the latter cannot drink. The rest sip, savour and enjoy the moment … and the picture shows they do so in emphatic terms. Peter Pollock stands aloof. An hour passes, then two.

And then comes the hand of God. A policeman has been posted with the team to keep demonstrators and activists at bay. He comes enters the bathroom and looks at the fast bowler.

“Peter, why are you so glum? You guys have won a Test. Celebrate.” Like a conjuring trick, this upholder of the law fishes out a beer. It is a sign from the Almighty himself. Peter Pollock drinks.

That was 9 August 1965. The last day of the Test.

(This excerpt , with a few modifications, is from Arunabha Sengupta’s Apartheid: A Point to Cover. )