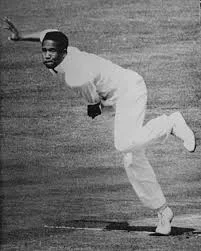

Garfield Sobers, born July 28, 1936, was simply the greatest all-round cricketer ever witnessed in the history of game. He was a freak of nature, who was the best of batsmen, most versatile of bowlers and the supreme acrobat among fieldsmen. Arunabha Sengupta looks back at the career of the man who was unique in the true sense of the word.

Demystifying the Sobers code

Ray Robinson called him “evolution’s ultimate specimen of cricketers.”

CLR James, with his penchant for infusing the game with sentiments of emancipation, went further, marking him “the living embodiment of centuries of tortured history… a West Indian cricketer, not merely a cricketer from the West Indies.”

Superlatives tripped liberally from tongues and pen of even the most prosaic and conservative chroniclers of the game, especially during the two decades when Garry Sobers reigned supreme. His giant shadow stretched across every department of the game, his mastery lending sparkle to every specialisation ever eked out of cricket, bar wicket-keeping.In the high noon of his dominance all those Jacks of all Trades, who had paraded themselves as all-rounders, took in the dimensions of his genius and scurried to find a new meaning of their lives and their cricket.

As a batsman he was undoubtedly the best in the world in his day, certainly the most sublime attacking stroke-player, and till this day stands as one of the most supreme wielders of the willow across the entire history of the game.

As a bowler, there have been many better, but none as versatile. He could take the new ball, run in quick and make it dart about. When the ball was older, he could spin it in time honoured orthodox manner. Or he could resort to turning it from the back of his hand, sharply and in both ways.

And as a fielder, he could pouch half-chances in the slip, and at leg-slip grab even those which did not register as chances at all. If, for the sake of variety he was placed in the covers, he could chase like a greyhound and pick up and throw in one action, searing, flat and accurate. He was undoubtedly the greatest all-round fielder of the era.

When he ended his career, he was the highest run-getter in Test cricket, with the highest individual score in an innings, the second highest wicket taker for West Indies and was third in world on the table of catches held by non-wicketkeepers.

In other words, he was a freak of nature, the likes of whom the world has never been seen before or since.

There have been attempts to decipher the Sobers code. What was it that made him this incredible force who swept through the cricketing world for almost twenty years?

Some have suggested it was the oddity of his being born with six fingers in each hand.

Others have delved deep into the life and the man’s own words, and have sought answers in the old cricket balls the young Sobers played with. They were scrounged from the rejects of the local Wanderers ground where Dennis Atkinson and others would have a hit. The balls, with ruptured seams, would be crudely stitched together by the local shoemaker, and would result in bizarre movements in the air.

Still others have put it down to the accident on the A34 near Stone in Staffordshire in 1957, with Sobers behind the wheel and the superbly talented Collie Smith sleeping in the back. The legend has often confessed that the death of Collie Smith had mortified him, and had led him to realise that from then he would have to play for himself and Smith.

But, to find a reasonable explanation of the stupendous feats we perhaps need to look at Lord’s 1973, the last series of the great man in England.

When Sobers, 31 not out at the end of the day, was approached by Clive Lloyd for a night out. Never once in his career did Sobers say no to an evening of entertainment. They visited some Guyanese friends in London, and then spent time with former off-spinner Reg Scarlett in a nightclub. The drinking, interspersed with dancing, went on and the evening gradually stretched and stretched till it was four o’clock in the morning and the sun was starting to peep through the other end of the sky. By then, Sobers was past any need to sleep. “I have so much liquor in my head that if I go home to the hotel and go to bed, I am not going to wake up,” he confessed to Scarlett. So, as the most obvious alternative, they went to Clarendon Court for some more drinks. And after a shower, Sobers padded up and walked out to resume his innings.

He played and missed the first five balls of the first over bowled by Bob Willis. And then the sixth struck the middle of the bat. And they continued to find the middle till he was 132, when he had to retire because of a desperate need to go to the toilet.

In the pavilion, he had his medicine — two glasses of port and brandy mixed together in a potent combination. And he went back to the crease to finish unbeaten on 150. We need to remember that at that time Sobers was past his 37th birthday.

This exploit should in no way be read as the ideal habits for aspiring cricketers. It is anything but. The incident just demonstrates that Sobers was a curiosity who can never be estimated within the normal parameters that generally constrain a mortal being. There is no point in trying to demystify his methods. He was gifted with a talent beyond the realm of earthly men of flesh and blood. And besides, for every tale of such late night drinking sprees there were countless days of backbreaking hardwork away from the focus of public eye.

Playing bugle to play cricket

Sobers was indeed born with six fingers in each hand. The first extra finger fell off before he was 10, jerked out with a piece of cat gut wrapped around the base and hauled off with a sharp tug. He played his first serious cricket match with 11 digits. The remaining additional finger was severed with the help of a sharp knife when Sobers was 14.

The greatest all-rounder the world has seen was brought up with his brothers by his mother. His father, a seaman working in the Canadian merchant navy, was serving on The Lady Hawkins when it was sunk by the Germans in early 1942. Sobers was just five at that time.

Along with his brothers, he took to the game early. At the local Wanderers ground he helped to put up numbers on the scoreboard and watched Frank Worrell, Clyde Walcott, Everton Weekes and others play their club cricket. His earliest games were played with a tennis ball on hard pitches. Sobers was the one of the few players to stand upright and play with a straight bat at the bouncing tennis balls.

Insurance salesman Dennis Atkinson, a Test player of the day, often left work early and got to the Wanderers to have a bit of extra hit before the other cricketers arrived. He looked for bowlers who could send down a few deliveries, and local groundsman, Briggs Grandison, suggested that young Sobers was good enough to have a go. Atkinson had Sobers bowl to him regularly, and often put a shilling placed on each stump, for the taking if the teenager could knock them off.

It was Atkinson who recommended Sobers to Captain Wilfred Farmer, the local inspector of police.The young lad was asked to turn out for the Police Cricket Club. To make the inclusion legitimate, he was asked to play the bugle for the police band.

When he went for trials at Barbados, Sobers stood in the covers in his shorts and picked up the ferocious drives of Clyde Walcott with supreme ease, something no fielder in the island could dream of doing. He caught the eye immediately, with his orthodox left-arm spin and his incredible fielding.

Sobers was just 16 and still playing in his shorts when he was chosen as a last minute replacement against the touring Indians of 1952-53. It was to be his First-Class debut. The family could not afford flannels and the Barbados Cricket Association presented Sobers with his first cricket outfit. Sobers bowled to Polly Umrigar, and started with two maidens. The Indian maestro got fed up at this little fellow tying him up and launched him over the Kensington stand for six. Two balls later, Sobers pushed a straight one through and bowled him as Umrigar played for turn. His figures for the match were 22-5-50-4 and 67-35-92-3. Not too bad for a 16-year-old left-arm spinner.

The ‘spirit’ of Test cricket

A year later, by now a regular for Barbados, Sobers turned out for his island against Len Hutton’s Englishmen. He picked up a few wickets, but the match was more memorable for his short innings. He was bowled by Tony Lock but survived as the bowler was called for throwing. That was the match in which Fred Trueman bowled him a bouncer which had Sobers in an awkward position. As he ducked, his bat jerked up, hitting him on the forehead. According to his autobiography, that was the last time Sobers ducked to a bouncer.

Sobers still played cricket on the street with his friends, and was engaged in one such game when a cable from the West Indies Board arrived requesting him to join the team for the Fourth Test at Trinidad.

Arriving in Port-of-Spain, he picked up a wicket in his very first over — getting Trevor Bailey caught behind. Perhaps it prompted Bailey to be his first-ever biographer. The Essex all-rounder published Sir Gary in 1976, and the book unfortunately was almost as slow and laborious as his batting.

The final bowling analysis Sobers managed on his debut was four for 75 from 28.5 overs, but Len Hutton scored 205 and West Indies lost by eight wickets. Sobers batted at No 9 and scored 14 not out and 26.

The next few years were not really sparkling with success, but the young man picked up plenty of nuggets of experience along the way which would stand him in good stead over the course of his career.

The strong Australian side visited the next year to humiliate the hosts in the Test series. Keith Miller and Ray Lindwall terrorised the batting with their lightning quick deliveries, and as a quaint diversion, also belted centuries with their bats.But, they also taught Sobers the valuable lesson of enjoying himself during the cricket tours. They banged on his door late at night, and sat with him with drinks, exchanging stories, making the young lad feel at home in the big league, and instructing him about the ‘spirit’ that should always accompany cricket.

Those were the days when the batting ability of Sobers was only partially recognised, and at Georgetown caretaker captain Atkinson sent him out to open the innings. It was a sacrificial manoeuvre, in a desperate attempt to protect the Three Ws from the new ball. Sobers struck 10 boundaries in a quick-fire 43, to give a minute preview of his potential.

On top of the world

An unhappy New Zealand tour followed, a country where Sobers never quite managed to enjoy success. And England in 1957 was a nightmare for West Indians, and Sobers did not have a great time himself. But, he did well enough in the tour matches to land himself a job as a professional for Radcliffe in the Central Lancashire League. He would go on to play there for five years, and then for Norton in the Staffordshire League.

The English pitches taught him the virtues of playing balls according to merit. The conditions also prompted him to try his hand at medium pace. It took many days to perfect his action and learn the intricacies of swing, but Sobers became good enough to open the West Indian bowling.

And finally, he also experimented with wrist spin, and soon was to bowl in all three styles in Test matches.

Yet, at the end of the second home Test against Pakistan in 1958, Sobers as an international cricketer had accumulated just moderate returns. His 16 Tests had brought him 856 runs at 34.24 and 21 wickets at 40.33. He had shown promise but little of it had been converted to results at the highest level.

The world of cricket underwent a startling change at Kingston during the third Test. Sobers, sent in at number three, scored his first hundred and made it huge. Indeed, he made it enormous. With Conrad Hunte he added 446 for the second wicket before a direct hit from mid-off ended the opener’s innings for 260.Sobers continued to pile on a massive score to break the world record set by Len Hutton two decades earlier. He ended unbeaten on 365, and it stood for 36 years as the highest individual innings in Test cricket.The milestone resulted in a minor stampede of enthusiastic fans on the pitch. Cables and messages of congratulations followed from around the world, including one from Hutton himself. In his homeland, Barbados Cricket Association and the government had a motorcade waiting for him at the airport.

More importantly, it was a watershed moment for Sobers the batsman. His willow entered a phase of supreme brilliance that remained undimmed till his retirement 16 years down the line. From the Kingston match till the end of his career, Sobers scored 7176 runs in 77 Tests at 62.94 with 26 hundreds. He had come a long way from the rookie left-arm spinner who was also quite handy with the bat down the order. He was now the very best batsman in the world.

The world stands conquered

After the 365, Sobers commenced a period of making up for lost time. All those hundred-less years were compensated. Centuries in each innings followed in the very next Test. Three more hundreds were amassed in the 1958-59 tour of India. He started with 142 not out in Bombay. Unfortunately run out for 198 in Kanpur, he missed out on another double hundred. But, 106 followed at Calcutta. It was his sixth hundred in the last six Test matches.

And after Pakistani umpires openly targeted him in a series of most ridiculous decisions, Sobers returned to West Indies to score 226 against England at Barbados, adding 399 with Worrell. Sobers and Worrell became the first pair to bat through two complete days in Test cricket. Two more hundreds followed in that series.

The 1960-61 tour to Australia was an epochal landmark in West Indian cricket. Worrell became the first black man to lead West Indies on an official cricket tour. The quality of cricket during the series remained exhilarating and the spirit exemplary.

The first Test in Brisbane became the most talked about game in history, ending in the first-ever Tie. Sobers etched his name in sparkling characters over that gilt edged page of history by scoring 132 splendid runs. Don Bradman, watching the innings, remarked that it was the greatest he had ever seen in Australia. It also brought Sobers his 3000 runs in just his 33rd Test.

Another sublime 168 followed at Sydney, and in the final Test at Melbourne he hit 64 before bowling 44 overs, 41 of them unchanged, to capture five wickets for 120 in front of a record crowd of 90,800. Bradman was impressed enough to recommend him for the South Australian team. For the next few years Sobers turned out in the Sheffield Shield. It was for South Australia under the captaincy of Les Favell, Sobers was encouraged to try out all styles of his bowling in match situations.

This was the period of absolute supremacy. Sobers had no parallel in the world with the bat or all round skill. Every series saw him score hundreds in torrents. Or he would be rolling his arm over to capture five wickets. All the while he would be witnessed performing spectacular dives to come up with near miraculous catches.

From 1961 to 1968, Sobers scored 3106 runs at 63.38 with nine hundreds and captured 125 wickets at 27.93 with every type of bowling with five five-fors. During this period he held 60 catches as well. All this accomplished in just 33 Tests.

He was named the Wisden Cricketer of the Year in 1964, for his 332 runs and 20 wickets during the riveting England tour of 1963. However, his genius reached new levels when he went there again in 1966, this time as captain. In five Tests of extraordinary accomplishments, he transfixed crowds and befuddled statisticians, scoring 722 runs with three hundreds at 103.14, capturing 20 wickets at 27.25 and holding 10 catches. The third hundred, 174 at Leeds, was an unique gem in all this glitter, scored in 240 minutes with 24 boundaries, with 103 scored between lunch and tea. He proceeded to capture five for 41 in the first England innings, ending it with a spell of three for nothing from seven balls. And coming back he took three for 39 in the second as the rubber was secured. His performances during the tour earned him a simple title: ‘King of Cricket’.

The uneasy crown

Yet, king that he was on the field, he was a reluctant leader when under the insistence of Worrell, the reins were passed on to him in 1965-66. Sobers the night-owl was never one for discipline or curfew, and he was not going to impose it on his team. Moreover he had no time for inter-island politics which formed a big component of team selection in West Indies. There were plenty of considerations and dilemmas but finally he accepted the job.

He started impressively, capturing his 100th Test wicket and leading West Indies to their first series triumph against Australia. Then he had that magnificent series in England, laying to rest any misgiving that captaincy might affect his performances with bat and ball.

In 1966-67, Sobers took his side to India. He hit half centuries in all five innings, picked up 14 wickets in three Tests and won the series comprehensively. He was acknowledged as the champion cricketer of the world, and he seemed to have no limitation. And with additional responsibility, Sobers perhaps experienced a new phase in his life.

Always ready to go out with the local girls of whatever country he was touring in, he now fell head over heels in love with 17-year-old Indian actress Anju Mahendru. It made huge headlines, and the engagement was announced with a lot of fanfare. The wedding of Nawab of Pataudi and Sharmila Tagore had taken place only recently, and the press was delighted with a possible encore.

The engagement had to be broken off later as the relationship could not survive the challenges of long distance and separation. Sobers eventually got married to an Australian girl, Pru Kirby.

However, during the 1966-1967 period it seemed that the additional responsibilities of captaincy had been taken in the stride of his infinite abilities.

Things changed when Colin Cowdrey’s Englishmen visited the Caribbean in 1967-68. Sobers was his imperious self, slamming 113 and taking three for 33 at Kingston and following it up with 68 at Bridgetown. However, he made the fatal decision in Port of Spain.

Fed up with the negative methods of the Englishmen who bowled 12 to 13 overs per hour all through the series, Sobers declared the second innings at 92 for two, setting the visitors a challenging target of 215 on the final day. Unfortunately, England got there with seven wickets in hand, and the barbs of criticism flew thick and fast. According to Sobers it had been a team decision, in consultation with manager Everton Weekes, with an eye on the turning wicket and three spinners in the team. But the players and management did not back up his claims. Weekes made matters worse by saying, “You can’t tell Garry Sobers anything.”

From an extremely successful skipper, he slipped into the role of a villain who had lost a Test match because of a whimsical decision. He tried hard to even things out in the final Test at Georgetown, hitting 152 and 95 not out and taking six wickets, but England hung on for a draw. The decision had cost Sobers and West Indies the series.

By now Wes Hall and Charlie Griffith, the two pace bowlers who had been the architects of wins during the glorious years, had passed away from the scene. With little or no pace available at his disposal, Sobers was forced to open the bowling, and then he teamed up with Lance Gibbs and sometimes David Holford to form a spin attack as well.

By now, a floating bone in the shoulder had started hampering his wrist spinning action. Hence, he was back to his orthodox slow left-arm bowling. With this style he picked up six for 73 to bowl West Indies to victory in the first Test at Brisbane during the 1968-69 series. The genius of Sobers had unveiled yet another facet.

However, after that it was all downhill for his captaincy. Australia came back to win three of the remaining four Tests. They lost the series in England in 1969. And while he battled on, scoring three hundreds and a ninety in the home series against India in 1970-71, the visitors made history by triumphing in the Caribbean for the very first time.

Following this, an incredibly drab stalemate was played out across five Tests against a limited New Zealand side.

The personal form of Sobers did not suffer, but the West Indian team had been reduced from being a champion side to wallowing in mediocrity. Battling with knee problems, Sobers made himself unavailable for captaincy after the home series against New Zealand in 1972.

Great feats continue

The great man himself did have incredible moments away from the Test field as well. When Nottinghamshire hired him in 1968 for £5,000 per season, accommodation, car and tickets to Barbados, Sobers enjoyed a rollicking season. It culminated in the six sixes in an over struck off Malcolm Nash in Swansea.

Leading Rest of the World against England in the summer of 1970, Sobers unleashed perhaps his best all-round performance ever. At Lord’s, in seaming conditions, he made the ball talk, picking up six wickets for 21 in 20 overs, bowling England out for 127. And then he proceeded to hammer 183 with the bat in a total of 546. The Rest of the World took the series 4-1. Sobers scored 583 runs at 73.50 and captured 21 wickets at 21.52. Unfortunately, contrary to the assurance given to Sobers at the beginning of the series, these matches were not accorded Test match status.

And then there was the incredible innings for World XI in 1971-72 against a fire-breathing Dennis Lillee. According to the autobiography of Sobers, on a Perth wicket that made the ball fly at the rate of knots, the pace of the young Australian fast bowler had prompted openers Sunil Gavaskar and Farokh Engineer to refuse genuine singles to avoid getting on strike.Lillee had got him for a duck in the first innings with an unplayable delivery. In response, in the following match at Melbourne, Sobers had bounced Lillee and intimidated him into scooping a catch to mid-off. When Sobers came in for his knock, Lillee was charged up, running in at furious pace.

What followed was carnage. Sobers started with a blistering square-cut past point that sped to the fence at a rate almost approaching the speed of light. It set the tone for the day. When the ball was up, he drove — with timing and power beyond the capability of lesser men. When it was short and wide, he cut or drove off the backfoot with a ferocity that was primal in beauty and brutality. And when deliveries came rearing into his body, he rocked back to pull and hook, furious and fearless.

Lillee, Bob Massie, Terry Jenner and Kerrie O’Keefe combined into an intimidating attack. All of them were slaughtered with a blade that flashed in a manner both savage and sublime. The fast men were carted all around the wicket. The spinners were driven and lofted with uncanny quickness of eye and feet, and a thorough disdain for their length, line and reputation.

When he walked back for 254,the Australians applauded him all the way to the pavilion. Lillee remarked, “I have had by arse cut properly today. I had heard about you and read about you and now I have seen you. I really appreciate it.”

Unfortunately, even this fascinating series did not get into the Test match record books. On the other hand, the one sided Australia versus Rest of the World affair of 2005 has found its way to Test recognition.

Rhodesian Affair

It was while leading Rest of the World in England in 1970 that Sobers was approached by Eddie Barlow to play a double-wicket tournament in Rhodesia. As a professional cricketer, and absolutely ignorant in matters of international politics, Sobers saw no reason to refuse. He was being paid £600 for two days of effort, which seemed an excellent deal. He partnered Ali Bacher and enjoyed himself. He also had lunch with Ian Smith, the Rhodesian premier. After the meeting, he described Smith as a great man to talk to.

This led to all sorts of complications.The leader of the neighbouring Gambian nation raised objection with a West Indian dignitary visiting their country at the very same time:”How can we be blood brothers when one of your greatest ambassadors is having tea with Ian Smith and telling the world how good he is?”

Forbes Burnham, the Marxist Prime Minister of Guyana, announced Sobers would not be welcome in his country unless he apologised. Dr. Eric Williams, Prime Minister of Trinidad, also voiced concerns once Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi declared that she would not allow the Indian team travel for the forthcoming tour unless the matter was sorted out. Williams sent Wes Hall to speak to Sobers and find out what exactly was going on.

Errol Barrow, the Prime Minister of Sobers’ native Barbados, was in America and cut short his trip because of the furore. Finally, after discussions with the all-rounder, Barrow drafted a letter to the Guyana Board of Control for Sobers to sign. This apology was publicised in the papers and broadcast across the islands, and finally brought an end to two months of front page news.

Even Sobers had problems with selectors

Even a superb performer like Sobers had to deal with some problems with the selectors during the last phase of his career. After recovering from knee surgery, he participated in a match for Barbados and was happy with his fitness. However, Jeff Stollmeyer and Clyde Walcott, the selectors, insisted that he had to play more matches to prove his fitness in order to be selected against Australia in 1972-73. A furious Sobers, who in his heyday had been persuaded by the same men to turn out in spite of his injuries, refused to play in any extra match. He was not picked for the series and West Indies lost.

Ian Chappell, the Australian captain, did not help the cause of the selectors when he left Caribbean with the remark, “We may have beaten the West Indies, but I don’t believe we have achieved much because we had come to play against Garry Sobers.”

This led to a furious outburst of emotions of the Caribbean fans. They had severely criticised Sobers’ omission, and Chappell’s words were like a keg of gunpowder touched with flame. Walcott was booed, jeered and even threatened. Walcott’s son was taunted in his school. When Sobers scored that drink-powered 150 at Lord’s in the very next series, the public wrath against Walcott reached its zenith. The argument on the lips of everyone was if Sobers was good enough to score those runs now, he must have been equally good against Australia. Sobers had to appear with Walcott in public to calm things down, announcing that there was no problem between him and the selectors.

After his triumphant England tour of 1973, Sobers played one last series — against England at home in 1973-74. It was not an ideal swansong, and he managed only one fifty in the four matches. Derek Underwood bowled him for 20 in his last innings at Port of Spain, bringing the amazing career to an end.

Sobers ended with 8032 runs in 93 Tests, at an average of 57.78. The aggregate remained a record for eight years before Geoff Boycott went past it in 1981-82. The 26 centuries Sobers scored stood second only to Don Bradman’s 29 at the time of his retirement.

With the ball, Sobers captured 235 wickets at 34.03, with six five-fors. And in his 93 Tests he took 109 catches.

The batsman

A most natural strokeplayer, Sobers was said to have at least three strokes for any ball. His natural instinct was to attack, and that he did without restraint. According to Barry Richards, Sobers was “the only 360-degree player in the game” —from his back lift to follow through, the bat traversed a perfect and complete circle.

However, as his average indicates, Sobers was much more than pure attack. His style was based on the solid substance of his back foot in perfect level with the off stump, letting him know which balls could be left alone and which had to be played. When he drove through the off-side he looked at once classy and fierce. In his cuts and pulls it was brilliance in brutality. The remarkable feature of Sobers was the number of runs he managed to make while batting low down the order, collaborating with the tail. He hardly ever farmed the strike, preferring to protect the tail-ender by arming him with his confidence.

The genius of Garry Sobers’s dexterity with the willow spared no bowler in the world © Getty Images

While he was known to be a backfoot player with excellent eye and fabulous timing, his game was much more than that. Every bowler he played was studied with detail. And soon, he picked up tell-tale signals from the run up and the last few steps prior to delivery, to know exactly what type of delivery was coming at him. Although he stayed absolutely still until the ball was released, this extra fraction of a second enabled him to get into position quicker than most. He preferred to read spinners off the hand rather than in the air or off the pitch, and could dance down the wicket with tinkle toed grace.

And his entire set of methods and repertoire was self-developed, untaught and uncoached.

The Bowler(s)

When he made his debut as an orthodox left-arm spinner, young Sobers had the ability to maintain accuracy through long spells. He did not turn the ball much, but varied his length, and mixed the straighter one amongst his normal breaks. While with Radcliffe, he added the other dimensions to his bowling. The back of the hand Chinaman bowling helped him purchase appreciably more turn. Often even the wicketkeeper went the other way to his googly. His shoulder, however, fell prey to his bowling the wrong ’un too often.

As a fast-medium bowler, he could be quite nippy off his 11-step run up. Neil Harvey once said that on occasions Sobers could be faster than Wes Hall. His bouncer was indeed more difficult to pick since it accompanied no change in his action. Not many batsmen could successfully play the hook off him. His natural ball was the inswinger, and it moved quite a way. Geoff Boycott fell prey to his late inswing quite often, the ball trapping him leg-before multiple times. Yet, he sometimes wasted the new ball swinging it too much and too often down the leg side. His outswinger did not possess that extravagant amount of movement, but could straighten or leave the bat just enough to pick up an edge.

Above all no bowler could lay claim to the amount of versatility Sobers brought to the table, switching between styles according to the conditions.

The Fielder

As a fielder, Sobers was brilliant in the slips, and fast in the covers, but it was at backward short leg and leg-slip that he turned into an acrobat. Standing there to the off-breaks of Lance Gibbs, he enjoyed being in the game every ball. Sometimes he would creep up and hold the ball off the face of the bat. Only once was Sobers hit while fielding close in. To a tossed up ball from Gibbs, Ian Chappell went forward and at the last moment changed his stroke to a sweep. It came to him like a bullet, hit him on his chest and Sobers clutched it and held it there. Chappell stomped off with an agonised cry of, “Sobey, you b*******.”

Sobers practiced regularly to the slip machine. He would bounce balls off the wall and the ground to sharpen reflexes. As a youngster he would throw stones at mangoes and catch them before they fell and burst on the ground. He also sharpened his skills by hitting a table-tennis ball against a wall over and over again.

The other facets of versatility

Additionally, Sobers was a wizard with numbers. He could do calculations without pen, paper or calculator, and seldom had to look at the scoreboard during a match. Every run and wicket was securely stored in his head. Yes, in many ways Sobers is way beyond the parameters meant for lesser mortals.

According to Fred Trueman, Sobers “had a great cricketing brain and his thought processes were lightning quick”.

Sobers was also a scratch golfer during his playing days and remained so after his retirement. Throughout his career he was an enthusiastic and incorrigible punter on horses and a major patron of the casinos. His versatility did not end there. In 1967, he authored Bonaventure and the Flashing Blade, a children’s novel in which computer analysis helps a university cricket team become unbeatable.

In 1975, Garfield Sobers was knighted for his services to cricket. In 1998, the Barbados government proclaimed him a National Hero, and he was accorded the honorary prefix “The Right Excellent.” Five years later, in 2003, he was appointed Officer of the Order of Australia for his stint with South Australia in the Sheffield Shield. The next year, the Sir Garfield Sobers Trophy was unveiled, awarded annually to the International Cricket Council Player of the Year.

Sobers coached Sri Lanka for a while in the 1980s before moving to the role of commentator and critic.

While the numbers speak eloquently about the almost miraculous deeds that Sobers performed through his career, it takes a look of a photograph or a clip of one of his flourishing strokes through the off side to get a flavour of the cricket the man played. Every moment on the field for him was an exhilarating expression of his infinite zest for life, unbridled, unrestrained and forever unequalled.The elegance, the force and the charm of his game resonated in one word — natural.

In 2000, Sobers was named one of the five Wisden Cricketers of the Century, along with Don Bradman he was the only unanimous choice of the panellists. And like Bradman he may be one of those few unique players in the history of the game— cricketers who are erratic mutations in the order of nature, to be witnessed only once across the bank and shoal of time.