Malcolm Marshall, born April 18, 1958, was perhaps the greatest of the famed West Indian fast bowlers — certainly the most terrifying. Arunabha Sengupta remembers the legend who passed away at the young age of 41.

Crème de la crème

The West Indian team dominated world cricket for two decades like no other band of men.They did not just vanquish teams, they terrorised them. Viv Richards, Godron Greenidge, Clive Lloyd and the others pummelled bowlers into submission around the world. And then opposition batsmen — the best and the boldest — would brace themselves before taking guard against the meanest pack of pacemen ever. Four of them, each brimming over with unique talent, operating at pace like all-consuming fire, would rage at them, over after relentless over, right through the innings. It was a lethal cocktail of quality and quickness, an assembly line that churned out tall, strapping men who could hurl a ball down the wicket at the speed of bullets and hunted in fearsome foursomes.

Amongst all these tall, dark, devastating men, there dawned one who hardly reached beyond average height and build, by no means gifted with the imposing physical presence of his fast bowling buddies. But, for once, size did not matter as this slight man emerged as the most lethal of them all.

The pace bowling pool of the West Indians of the 1970s and 1980s overflowed with talent that has never converged within the same space-time co-ordinates before or since. Andy Roberts, Michael Holding, Joel Garner, Colin Croft, Pat Patterson, Wayne Daniel, Sylvester Clarke, Ian Bishop, Courtney Walsh, Curtly Ambrose … the names were numerous into submission all of them great, fiery, skilled and supremely fast. And even within this whirlwind wealth of wonders, that short man ended up standing taller than the rest.

Opinions do vary, but Malcolm Marshall is generally considered to be crème de la crème, the finest, the fastest and the meanest of them all on the cricket field. Besides, he was by far the best batsman among the fast men, almost an all-rounder. His willow was good enough to score seven First-Class hundreds, but never did he lose the fun and frolic that comes with a fast bowler swinging merrily from late in the order.

At an unimpressive five feet, 10 inches, whatever he lacked in height was made up by lightning- quick run up, followed by the fastest of releases.

Roberts ran to the wicket deadpan and deadly, Holding glided silently like an engineless Rolls-Royce, Garner ambled in with his huge strides delivering the ball from the clouds, Croft charged in like a raging bull. Marshall sprinted and slithered to the crease, at curious acute angles. His chest remained open as he delivered the ball with a whipping movement of the right arm. The action did not telegraph the nature of the swing. Whatever followed was often too quick to decipher. His shorter stature enabled a wicked, skiddy bouncer, which often thudded into the face of the most accomplished of batsmen.

But, his craft, built on raw pace, did not end there. It was enhanced by weaponry of the sharpest kind. He could swing it both ways, with his hand rather than movement of the body. This made his swing as difficult to read as the leg-breaks and googlies of the canniest leg-spinner. From Dennis Lillee he picked up the art of leg-cutters and bowled them with destructive effect on slow, dusty pitches. When his whims willed, he could change his pace, varying between express, lightning and just fast, or even slowing down to medium. And when the situation demanded intimidation, he could boost his lethal strain by coming round the wicket and hurtling them at the batsman’s body, the most dangerous sight in cricket since the days of Bodyline.

From forcing the bat out of Sunil Gavaskar’s hands to picking cartilages out of the ball after rearranging the face of Mike Gatting, the tales of his deeds of destruction are plenty. Yet, once the pulverising battle was over for the day, he was perhaps the most likable of foes as he put his feet up and sipped his favoured brandies.

The rookie

Born in Barbados, Marshall idolised Garry Sobers. Indeed, he wanted to be so much like Sobers that even well into his international career captain Clive Lloyd often threw him the ball with the words, “Come on Sobey, have a bowl.” It was the Sobers hundred at Kensington Oval against the New Zealanders in 1972 that sparked the cricketing ambitions of the young Marshall. And like Sobers he had to rise to greatness after wading through personal tragedy.

Marshall was just one when he lost his father in a traffic accident. He was brought up by his mother and taught the basics of the game by his grandfather.

He was taking his first tentative strides in the world of serious cricket when the West Indian Board was thrown into confusion by the World Series of Kerry Packer. As a result of the departure of stars, Marshall was taken to India in 1978-79 after just one First-Class match for Barbados. The strong Indian batting line-up plundered runs off him in the three Tests, but the rookie bowler took plenty of wickets in the tour matches.

The Indian tour defined his career in two important aspects. Hampshire officials were suitably impressed to recruit his services for the next season. And, excessive appealing from close to the wicket induced a long-lasting antagonism towards Dilip Vengsarkar. Through the eighties, Vengsarkar remained one of the best batsmen of the world, and Marshall ran in with added fury whenever the Bombay batsman took guard.

At Nottingham in 1980, Marshall bowled alongside Roberts, Holding and Garner for the first time, forming a four-pronged attack more fatal than the world had seen. There were sparks of promise from the tearaway youngster, as in the Old Trafford Test when he got Mike Gatting, Brian Rose and Peter Willey in quick succession. But, he had to wait another two years to become a regular in the side.

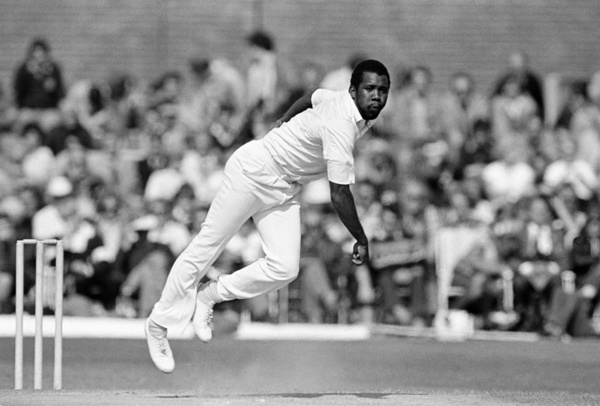

Malcolm Marshall… terrorised batsmen with the cricket ball © Getty Images

The peak years

It was when the Indians visited in 1982-83 that Marshall picked up 21 wickets in the series, including his first five-for at Port-of-Spain. He had been out of the side for a couple of years and had earned a recall after capturing 134 wickets during the English summer. From then on, he remained a permanent fixture in the side till the end of his career.

Marshall enjoyed a fantastic Prudential World Cup, picking up 12 wickets at 14 apiece at the economy rate of 2.50. In the semi-final against Pakistan he bowled at his fastest best, taking three for 28. He also struck Vengsarkar on his jaw during the second group match between the teams, forcing the batsman to retire. However, West Indies surprisingly succumbed to India in the final.

That winter the team travelled to the land of the recent World Cup champions to avenge the loss, and it was this series that marked the emergence of Marshall as an all-time great bowler of fearsome repute.

The series started at Kanpur, and India had the West Indians struggling early on with a few quick wickets on a sluggish, low track. Gordon Greenidge and Augustine Logie led a recovery before Marshall walked in at number eight and hammered a career best 92. India started their response with just an hour remaining on the second day. Marshall charged in at furious pace, the lack of life in the wicket hardly a hindrance.

Gavaskar snicked him for a second ball duck. Mohinder Amarnath followed, without bothering the scorers, wrapped plumb by a ball of scorching pace. Anshuman Gaekwad was the next to go, fiddling at a delivery outside the off stump. And finally, Marshall ran into bowl to Vengsarkar, who had scored 14 of the 18 Indian runs till then. The ball pitched on the leg and middle, cut away with blistering venom and took the off-stump. India ended the day on 34 for five, Marshall had taken four.

After India followed on, Marshall continued in the same fierce vein in the second innings. The bat flew from Gavaskar’s grip, struck by a ball that came at him like the bolt of lightning. Both the openers fell to him within the first three overs. Vengsarkar scored 65 before Marshall had him caught off the hook. He took eight in the match, and the dominance he established paved the path the series would follow. West Indies routed India 3-0 and Marshall picked up 33 at 18.81. On the Indian tracks, only a genius could aspire to such figures while bowling fast.

Back home, he picked up 21 against the visiting Australians — which would be his lowest tally in seven continuous series starting from the Indian odyssey. This included five for 42 at Bridgetown and five for 51 at Kingston. A greater triumph perhaps came against the test of his values. Offered a million dollars to join the West Indian rebel tour to South Africa, Marshall refused.

The next tour perhaps saw the best of the great fast bowler, certainly the most heroic facet of his mettle. At Birmingham he did not pick up too many wickets, but ended the career of Andy Lloyd within half an hour of his foray into Test cricket. The ball crashed into the head of the unfortunate debutant, landing him in hospital.

At Lord’s he picked up six for 85 in the first innings, before Greenidge scripted that fairytale triumph, chasing 342 and winning by nine wickets.

It was at Headingley in the next Test that one saw the Marshall spirit at its absolute crest. He bowled just six overs in the first innings, before going off the field with a broken left thumb after attempting to stop a Chris Broad stroke at gully. The West Indians were on 290, Larry Gomes a stroke away from century, when the ninth wicket went down. The English fielders, believing the innings to be over, were on the verge of leaving the field when in walked Marshall, striding to the wicket, proceeding to bat with one hand. He stayed with Gomes long enough for the left-hander to get to his hundred. In between, he enjoyed himself, steering a boundary with his lone hand. As England, trailing by 32, walked out to bat yet again, Marshall sprinted in, the ball clutched in his good hand, the lower part of his left arm encased in pink plaster. He skittled seven batsmen for just 53 off 29 blistering overs, including that of Graeme Fowler caught and bowled with one hand. He missed the next Test but was back at The Oval for the fifth as England was dealt out the blackwash, taking five for 35 in the first innings. He played four of the five Tests but his tally of wickets read 24.

When West Indies toured Australia, Marshall picked up 28 more, including five in each innings at Adelaide. This was his first ten wicket haul in Tests, which speaks volumes about the formidable giants with whom this supreme bowler had to share the spoils.

Four months later, he had done it again, with four for 40 and seven for 80 against New Zealand at Bridgetown. It was a four match series, and Marshall plundered 27 wickets.

England visited in the early days of 1986, and Marshall set the tone of the series by pulping the nose of Mike Gatting in the first One-Day International at Kingston. His tally in the five Test blackwash was 27.

The sequence of 21 plus wickets was broken as West Indies toured for a three match series in Pakistan. However, Marshall picked up 16, with five for 33 at Lahore as West Indies squared the series after a surprise loss in the first Test.

The Englishmen were once again subjected to a rout a couple of series later, as the season of four captains in 1988 saw Marshall scalp 35 at just 12.65. It included seven for 22 at Old Trafford of which five came in an hour. Marshall was bowling with guile by now, the bouncers limited to a few, but with plenty of gilt edged weapons added to the armoury.

The transition

Batsmen still did not have his measure, but there were challenges at home. Fast bowling remains a trade of the young, and the hulking frame of Curtly Ambrose cast its long shadow on the future of batsmen — with the giant form of Courtney Walsh at the other end. Marshall was still feared, but fresher legs and younger shoulders were at hand. In the Australian tour that followed, Marshall did well enough, with 17 wickets at 28.70. However, Walsh got as many and Ambrose led the tally with 26.

Regardless, the older man charged in again, in his finest form, when the Indians arrived in West Indies, led by the age-old rival Dilip Vengsarkar. Five for 60 at Bridgetown was followed by 11 wickets at Port-of-Spain. Nineteen wickets at 15.60 did not seem too bad for a veteran. But, that particular series saw the advent of another superb pace bowling talent answering to the name of Ian Bishop.

Marshall continued to bowl for another two and a half seasons, as the most experienced of a spectacular clutch of weapons, but no longer the most potent spearhead. In his last years, he was relegated to playing a supporting role for the younger lot as they unleashed a new era of terror on the batsmen around the world.

He played final series in England, at The Oval in 1991 — the famed ‘leg-over’ Test being his last match. West Indies lost by five wickets and England squared the series. It was the end of an era, as two men who evoked the greatest fear in the hearts of opponents passed away from the scene together. The world saw the last of Malcolm Marshall with the ball, and Viv Richards with the bat.

Marshall ended with 376 wickets, an West Indian record till Walsh went past him seven years later. His average 20.94 remains the best among bowlers with more than 200 wickets. Only Dale Steyn and Waqar Younis in the 200-plus club boast a strike rate better than Marshall’s 46.7.

The great fast bowler put on the Caribbean maroon in the 1992 World Cup, but finished with just two wickets in five matches. He continued for Hampshire for two more seasons. Even in the county games, on the dullest, drabbest of days, he ran in as committedly as ever, sending the quivering batsmen scurrying for cover throughout the long English summers.

Memories

There is a famous story about Ray East and David Acfield, two Essex spinners, and tail-enders terrified of the thought of facing Marshall. They used to wait by his car and offer to carry his bags to the dressing room. When the fast bowler asked why, they replied: ”Well, Mr Marshall, we thought you might consider a couple of half volleys and if they’re are nice and straight we promise to miss them!”

Marshall became the coach of West Indies in 1996. During the 1999 World Cup the world was aghast when it was discovered that the great fast bowler was afflicted with colon cancer. As the cricketing community turned speechless, Marshall gave up coaching and fought valiantly. In the end, he could not defy that cruellest of bowlers. The man who had been feared by batsmen the world over was pitiably wasted and shrivelled by the time death breached his final defence.

The news of his demise at the age of 41 sent the world into shock, and tributes flowed in from far and wide. His memory was recalled with fondness tinged with fear and respect that he had invoked all through his career

Cricket matches are now played in his name in various parts of the world. The road leading to the entrance of Rose Bowl, Hampshire’s home ground, is now known as the Marshall Drive.

However, the most apt tribute to his memory is perhaps the Malcolm Marshall Memorial Trophy, awarded to the leading wicket-taker in each series between England and West Indies. Fitting enough for someone who relished these encounters, who capturedas many 127 wickets in these contests at 19.18.