Alan Melville, born May 19, 1910, had one of the most curious careers. He led in all but one of the Tests he played in, overcame incredible injuries, and scored four Test hundreds in consecutive innings with an eight-year interlude in between. Arunabha Sengupta recalls the most graceful batsman of his generation.

Injury-prone

By all reason and rationality, Alan Melville should not have ever made it to the crease in big cricket.

Before arriving at Oxford from the Cape Province, South Africa, he had been involved in a car crash that had left him with three fractured vertebrae. His back never quite recovered, and since that fateful accident he seldom got by a full day without periods of excruciating pain.

While at Oxford, he developed severe problems with his knee. And then, as captain of the University side in 1932, he broke his collar bone in a game against Free Foresters by colliding with his batting partner Pieter van der Bijl.

Melville’s hands were also permanently bruised because of the curious way he held his bat, and had to have special gloves made for him with extra padding.

Yet, he did graduate to top level, scoring 78 and 103 in that famous timeless Test at Durban in 1939, before the Second World War brought a halt to International cricket.

During The War, his affair with misadventures continued. While training with the South African forces, he

suffered a severe fall, and that restarted all the pain and problems associated with his old back injury. For almost a year he creaked along, wearing a prescribed steel jacket, every movement carried out gingerly, with caution and metallic clangs.

But, when cricket resumed after the atrocities, he was back as the South African captain, scoring 189 and 104 not out at Nottingham, and 117 at Lord’s, completing hundreds in four consecutive innings with a gap of eight years in between.

Perhaps it was the tryst with injuries that made him immune to the most brutal of tactics seen in cricket. At Hove in late August 1933, while batting for Sussex against the West Indians, Melville, captain of the side, had walked out at number three after Ted Bowley had been hit. Herman Griffith and Manny Martindale were bowling leg theory — and although the wicket was placid, the balls rose sharply and made for the body.

Six foot two and frail, Melville stood tall and hooked happily. Not one bouncer was spared in what was perhaps the last demonstration of Bodyline. And when the bowlers pitched up they were driven. Half a century later, the ones who had seen the hundred he scored that day still remembered it with fascination. Throughout his career, he seldom left the short ball alone.

Grace and elegance

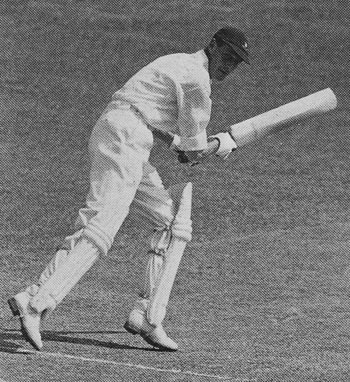

Melville was a sublime timer of the ball and, as a batsman, one of the most graceful to watch. His technique was almost flawless, executed with clinical perfection. He drove with élan, cut with elegance and his hooks were lissom and lithe. Off the legs, his strokes came off with delectable poise. He was good anywhere in the field and could be counted upon to pick up some useful wickets with his leg-breaks — which he later gave up for equally effective off-spin and occasional swingers.

Melville started out as a schoolboy cricketer of great promise and made it to the Natal side at 18. On his debut, he captured 5 for 71 against Transvaal with his leg-spin. In his second game, against Border, he hit 123 — showcasing his splendid technique and timing.

After discussions between South African selectors and Melville’s father, it was decided that the young man should make his way to Oxford, and his international career could be postponed for a few seasons. After being delayed by the car smash incident, he reached England in the autumn of 1929, and played for the University from the summer of 1930.

His first game was against the Kent attack of Frank Woolley and Tich Freeman, and he hit an attractive 78. And in the next match against Yorkshire, he scored 118 before being bowled by Maurice Leyland.

His University career was followed by some successful seasons with Sussex till 1935. During this period he led the side with a refreshing amount of experimentation and sense of adventure. He was only briefly hampered by an appendix operation at the end of 1934.

At the end of the 1935 season, Melville returned to South Africa and joined the Johannesburg Stock Exchange. Soon, in 1936-37, he was leading Transvaal to Currie Cup triumph — sharing the championship with Natal.

Test call up

When England visited in 1938-39, Melville was appointed captain of the side on Test debut and walked out to toss with Wally Hammond. His career at the highest level started with a duck, as he hit one back to Hedley Verity. In the second Test, he was injured while fielding and came in at No. 9 to score 23.

It was in the fourth Test that he finally got going, promoting himself to open the innings and scoring a pleasant 67. And in the timeless Test, he opened in the first innings to score 78 and moved down the order to No. 6 in the second and brought up his first Test hundred.

The injury during the War did lead to speculation that his playing days were over. But by 1947, he was back in the fray, leading the South African side to England. The centuries in both innings at Nottingham followed by the hundred at Lord’s made him the first batsman to score four consecutive hundreds against England in Tests. At Trent Bridge, his added 319 with Dudley Nourse in exactly four hours, then a world record.

According to Wisden, during the 189 at Trent Bridge, “he was never over-affected by his responsibility and he made many graceful strokes of perfect timing.” In the second innings, he was troubled by a pulled thigh muscle and limped painfully. However, injuries and pain never bothered this man and he scored an unbeaten 104, becoming the first South African batsman to hit a hundred in each innings.

But, in spite of his fourth hundred on the trot, South Africa were defeated at Lord’s and continued to lose in Old Trafford and Headingley. Melville, weakened, losing weight with fatigue and not helped by the post-war food rationing, was worn out. His form fell away after a 59 in the second innings of the third Test. It soon turned into a long disappointing tour, but Melville at least had the satisfaction of scoring 114 not out against his old county at Hove. He was named a Wisden Cricketer of 1948, and at the end of the tour announced his retirement from First-Class cricket.

Yet, when the Englishmen under George Mann visited in late 1948 visited South Africa, Melville was coaxed out of retirement. He hit 92 for Transvaal against the tourists and was invited to play in the first Test. However, characteristically, he had injured himself, this time his wrist bearing the continuous fury of fortune. So he missed the thriller at Durban, but played in the third Test at Cape Town. Dudley Nourse was the skipper and this was the one and only Test Melville played without leading the side. He opened the innings with Owen Wynne and was out to Roly Jenkins in both the innings after useful knocks of 15 and 24. He did not play for South Africa again.

Melville’s 11 Tests brought him 894 runs at 52.58 with those 4 hundreds in consecutive innings to go with 3 half-centuries. He never bowled in a Test match, but captured 139 wickets in First-Class cricket at an average of just under 30.

For many years Melville served as the selector of the South African cricket team. The man who fought his way through potentially fatal injuries through his playing career managed to live a full life before passing away at the Kruger National Park in April 1983.