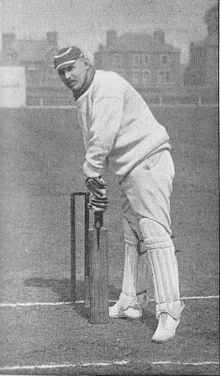

Arthur Shrewsbury, born April 11, 1856, was the premier professional batsman of his generation and, from the mid-1880s to the mid-1890s perhaps the best wielder of the willow in the world. Arunabha Sengupta looks back at the life and career of the man who was the first to score 1,000 runs in Test cricket, was a promoter of cricket tours, ran a thriving sports goods store and, later, took his own life.

Give Me Arthur

Did WG Grace really say those famed words: “Give me Arthur?”

As is the case of so many stories about Grace, we can never unravel the authentic from the apocrypha. It was in the 1920s that this statement first appeared in print, in an essay in The Cricketer Magazine by ‘A Country Vicar’ — real name Rev RL Hodgson. When Hodgson’s book Cricket Memories was published in 1930, this sentence made its way into immortality. In this second version, it was Grace’s answer to the query about his preferred partner to open the England innings.

This was of course picked up by those writers best described by the curious oxymoron — romantic historians. Neville Cardus and GD Martineau both used the phrase prolifically. It went down to mean that the great WG, when he took himself out of the equation, considered Arthur Shrewsbury as the greatest batsman of England.

Grace might have indeed said it. Or the statement might have been wrongly attributed to him. As in the case of legends, the exact origin of the comment does not really bother us. The essence of the sentiment remains unquestionable. From the mid-1880s, for over a decade, Shrewsbury was the best batsman of England, as also perhaps the entire cricket playing world. And that remains true even if we take the bearded forefather of batsmanship into account.

As in any saga of greatness, Shrewsbury’s brilliance is borne out by the numbers. In 1885 he topped the batting averages in England for the first time. He remained there till 1892, topping in every year other than 1888, which he did not play, and 1889 when he missed half the season. Apart from Grace, only Wally Hammond has had such prolonged dominance over the English First-Class scene across such a long period.

Yet, there were many other aspects of Shrewsbury’s career and life that defined an extraordinary man.

Relentless Zeal

According to biographer Peter Wynne-Thomas, “Arthur possessed the gift of patience and that, allied to his innate ability, produced the first of the great modern professional batsmen. Shrewsbury, it seems to me, must have realised as a teenager that he had the necessary gifts to be a good batsman and by sheer unremitting practice in the nets and in the local matches, set about developing the talent until he became the most complete batsman in England, if not the world. Before Shrewsbury came on the scene, batsmen, whether professional or amateur, allowed their natural aptitude to determine the standard of their cricket. Shrewsbury was not satisfied to let nature take its course. He developed batsmanship in the same way that modern athletes have used the science of training in the recent Olympics.”

Indeed, the relentless drive for perfection of Shrewsbury is almost without parallel. A plain hard-backed pocket notebook has passed on as one of his heirlooms. It was his diary maintained through a year and four months. The entries include details of Shrewsbury’s days spent at the indoor nets at Trent Bridge. The descriptions read as follows:

“18 December

Self bowled by A Attewell when not looking.

W Marshall bowled by self if bails had been on, but stumped same ball.

W Marshall clean bowled by Gunn.

Self clean bowled Henson.

Present: A Shrewsbury, Henson, Marshall, J Gunn, A Attewell

Noddy was present but did not play.

Dark day, light very bad.”

Of course one can understand a young cricketer keeping detailed notes of indoor practice in the winter. However, the date of the entry was December 18, 1900. The diary was maintained from December 1900 to March 1902. By then Shrewsbury was in his mid-40s, with 25 years of First-Class cricket behind him. All his contemporaries had long left the game. However, he was still one of the very best batsmen of England.

In 1902, at the age of 46, he topped the season’s batting average, pipping two batsmen whose names read Victor Trumper and KS Ranjitsinhji.

In the 1880s and 1890s, the verdict was almost unanimous. According to Charles Pardon, editor ofWisden: “Arthur Shrewsbury may without the least reservation be described as the greatest professional batsman of the day.” The other major cricketing reference of the day was not far behind. CW Alcock, editor of Lilywhite Annual, announced, “Arthur Shrewsbury stands out in bold relief among the cricketers of today as the professional batsman par excellence.”

Sitting in our times, we can transliterate ‘professional’ to the current meaning of the word and thereby succeed in making the sentences more accurate. Shrewsbury was indeed one of a kind, the greatest of his era and one of the best ever.

However, cricket was only a part of his active life. Teaming up with fellow Nottinghamshire professional, the great bowler Alfred Shaw, he set up a thriving sports goods manufacturing business. Shaw and Shrewsbury produced cricket bats, tennis rackets, boxing gloves, football and had contracts with firms across England and Australia. Besides, the same Shaw and Shrewsbury duo was responsible for several cricket tours to Australia, in that period when most of the visits were privately organised.

Shrewsbury not only managed the business of the tours, he was also the captain of England in seven Tests, the last professional cricketer to lead the country before Len Hutton was appointed in 1952. He also managed the first English Rugby Union football tour to Australia, the reason why he was away from England and did not play in the 1888 summer. Besides, the tours were utilised to generate contacts and business partners in the sports goods market.

And this complex character, in spite of all his sporting success and flourishing business, met a tragic end by his own hands.

The young Shrewsbury

Arthur Shrewsbury was born on April 11, 1856, at the family home in Kyle Street, New Lenton. He was the youngest among four brothers, and also had three elder sisters. When he was eight, the family moved to a terraced house in Wellington Square, Nottingham. His father William Shrewsbury was employed as draughtsman-designer in the lace firm of JT Hovey in the city.

The interest in cricket seems to have stemmed from grandfather Joseph Shrewsbury, who played for the Beeston team in the 1820s. Some of the maternal uncles of the Shrewsbury boys, with the family name Wragg, also seem to have played for Lenton. At least, the surname Wragg figures prominently in the Lenton team records of the 1840s.

As a result, all four Shrewsbury brothers were keen on the game. Apart from Arthur, Joseph and Edward played actively at school, while William made it to the Nottinghamshire county team and played a handful of First-Class matches.

It was in May 1867 that Arthur Shrewsbury’s name made it into the newspaper for the first time for cricketing reasons. He played alongside brother William for People’s College against High Pavement School.

At the turn of the new decade, the Shrewsburys started living in Queens Hotel, Nottingham. It was to be the home of Shrewsbury for 32 years.

William and Arthur both became members of the local cricket club, Meadow Imperial. Even in 1871, Shrewsbury topped the batting averages of the club. The next year, he joined the biggest local club of the day, Nottingham Commercial.

However, his first foray into the Trent Bridge County ground was during an important game which may seem strange as we look back from the current day. It was a match between Lace and Hosiery, played in June 1872 — a testimony to the key industry of Nottingham during that era. Shrewsbury, an apprentice draughtsman in the lace trade, was part of the Lace team. There were six county cricketers who featured in the game. However, the match was dominated by the 16-year-old Shrewsbury who scored 44 out of a total of 89.

By this time, Shrewsbury was playing plenty of cricket for the clubs. Commercial and Lace aside, he also turned out for Meadow Imperial and Castle-Gate. William was also active in the cricketing scene. When the Robin Hood Rifles team played a few matches, the scoreboard suddenly got enriched with the name of Privateer Shrewsbury.

In 1873, Shrewsbury was accepted in the Notts Colts team and the Nottingham Journal observed that he was the most promising player. That winter, brothers Arthur, William and Edward also played for the Meadow Imperial Football Club.

In 1874, Shrewsbury had a bad attack of rheumatic fever and it kept him away from cricket. It was probably this illness that made him prone to hypochondria throughout his career. There is a theory that it was the subsequent fear of terrible disease that led him to take his life later on.

First-Class cricketer

On a trip to North America in the late 1880s, a sports store called ‘Shaw and Shrewsbury’ was setup by Arthur Shrewsbury and his friend, Alfred Shaw

However, when he recovered and came back to the game in 1875, he made his First-Class debut. For the game against Derbyshire at Whitsuntide, four of the regulars were engaged in the North versus South game at Lord’s. Shrewsbury was drafted into the side, alongside fellow debutants wicketkeeper Alfred Anthony, and his former schoolmate from People’s College and later opening partner William Scotton. Shrewsbury batted at No 3 and made 17 and 10. The very same year, William also made his debut for the Notts. An old 1875 photograph of the county side shows the two clean shaven brothers flanking a hirsute squad of typical cricketers of the day.

By the summer of 1876, Shrewsbury had a contract with Notts County Cricket Club. He scored 59 against Marylebone Cricket Club (MCC) and followed it up with 118 against Yorkshire, sharing an opening partnership of 183 with Richard Daft. These knocks got him included in the Players side for the traditional fixture against the Gentlemen, and he finished the season with 65 not out against Surrey. The young man was already a force to reckon with.

Shrewsbury was not part of the England team under James Lilywhite that toured Australia in 1876-77 and played the first ever Test match. However, the tour was important for his subsequent career — it forged a strong friendship between his two business associates in the next decade, Lilywhite and Alfred Shaw.

When the next summer started, Shrewsbury made 119 at The Oval for the Players of the North against Gentlemen of the South.

If the scores of Shrewsbury were not spectacular during the late 1870s, another aspect of his character was soon making its presence felt. He was one of the first professional cricketers to stand up for his rights.

When Notts secretary Captain Henry Holden, the Chief Constable of Nottinghamshire, asked him to apologise for batting at the nets for some minutes more than the allotted time, Shrewsbury refused to apologise and was left out for the games against Middlesex and Lancashire. From a very early age, Shrewsbury was intensely aware that the public paid to watch him bat, and he was entitled to respect both in public and in the Notts Committee. After the suspension, when Holden patched things up by driving him personally to Trent Bridge for the next match against Yorkshire, Shrewsbury responded like a true professional by hitting a flawless 60.

In September 1879, Shrewsbury went on a tour to North America with a team led by Richard Daft. The voyage was terrible for the young batsman, with seasickness dogging him throughout. The tour also did not get him much success either, apart from a 66 in an odds match against the 22 of Canada. However, foreign travel broadens the mind. The commercial possibility of such tours was soon making an impression on Shrewsbury.

It was also probably during this trip that Shrewsbury and Shaw talked at length about the possibilities of setting up a sports store. Thus in 1880 was set up ‘The Midland Cricket, Lawn Tennis, Football and General Athletic Sports Depot’. In 1884 it was shortened to a simpler ‘Shaw and Shrewsbury’, much to the relief of the business associates corresponding by post.

The years 1880 and 1881 saw Shrewsbury the proud professional taking the stage yet again. In 1880 Shaw and he led a showdown with Captain Holden regarding payments for the Notts match against the visiting Australians. When a mutual agreement was reached, Shrewsbury batted out of his skin to help the county side beat the visitors by one wicket in a thrilling match. He was undefeated at the end and was chaired from the ground, borne on the shoulders of teammates Fred Morley and Mordecai Sherwin.

In 1881, Shrewsbury and Shaw led the strike of the Nottinghamshire professional players over an early season fixture with Yorkshire. This meant just three First-Class matches for the season. Hence, while they enjoyed the break, Shrewsbury, Shaw and Lilywhite put their heads together to arrange a World Tour — covering North America, Australia and New Zealand.

Afflicted with bronchitis, Shrewsbury missed the American of the tour with. But, with the doctors voicing their approval of the Australian climate, he sailed directly to Australia via Suez.

Perhaps the best game of the tour was against Victoria, when the Englishmen followed on 105 behind and then lost four wickets for 73. Shrewsbury scored an unbeaten 80 on a difficult wicket and the visitors managed a thrilling win.

In the first Test match at Melbourne, Shrewsbury made his debut and scored 11 and 16. He did not do anything special in the second Test as well, but in the third match at Sydney he top scored in both innings with 82 and 47. However, although he did not blaze the turf of Australia with his bat, the matches at Sydney and Melbourne ensured a profit of £700 for each of the three promoters.

The premier batsman

The next few years saw Shrewsbury slowly climb up the ladder to emerge as the best batsman of England.

In 1882 he hit 207 against Surrey in the August Bank Holiday encounter, adding a record 289 for the second wicket with Billy Barnes. However, he did not cross fifty again in the season. He made up for it during the following year. The summer of 1883 saw the county games played on dry, fast wickets. Shrewsbury passed 1000 runs in the season for the first time and Nottinghamshire won the top place in the championships.

In 1884, Shrewsbury and Scotton established themselves as a prolific partnership at the top of the order. The highlight of their association was the 119 run partnership against Sussex at Hove. In the same innings, Shrewsbury and Gunn added 266 for the fifth wicket, notching up a new world record. Shrewsbury went on to bat for six and a half hours and piled 209. That summer he played all three Tests against the visiting Australians, and excelled in his familiar role as a limpet on a sticky wicket, scoring 43 out of 95 all out at Old Trafford.

In 1884-85, the trio of Shrewsbury, Shaw and Lilywhite arranged their second tour to Australia. This time, Shrewsbury went as the captain of the side.

As skipper, he opened the innings for England for the first time in the first Test at Adelaide. He was not overly successful the first time, but in the second Test at Melbourne he hit 72 in the first innings. After winning the first two Tests, England lost a thriller at Sydney by six runs. And in the fourth Test, a murderous innings by George Bonnor clinched the match for the hosts.

With the series tied at 2-2, Shrewsbury scored a superlative 105 not out in the fifth Test helping England to a series winning innings victory. This was his maiden Test hundred and he could not have chosen the occasion with more precision. The leading Australian cricket writer Felix observed, “His play throughout was a treat to look at, and that neat and effective stroke of his between square-leg and mid-on is worth copying. He made a large number of his 105 in this spot. His defence was splendid, his cutting clean and telling, his timing could not well be excelled, and his care and judgment in dealing with enticing balls to the off formed a lesson which young cricketers, and indeed some old ones, could study and profit. During his long stay at the wickets, Shrewsbury never once lost his patience.”

England won the series 3-2, but due to the boycott of several matches by Billy Murdoch and his allies, the promoters could make only £150 from the tour. In the tours that followed, Shrewsbury continued to have strained relations with the Melbourne Cricket Club.

Now started the glory years of Shrewsbury. In 1885, he scored 1130 runs at 56.50, with four hundreds, batting almost eight hours to score 224 not out against Middlesex. The next best in the averages was Walter Read with 44.76. He was to remain the best bat in England for several years. It may be argued that WG Grace was past his prime by now and had been at the top of his game for 14 successive summers from 1868. However, it is fair to say that Shrewsbury was the best in England in spite of the presence of the Grand Old Man.

As if to prove the point, Shrewsbury carried his bat against Gloucestershire the following season, scoring 227 not out against WG Grace and his men, adding 261 for the second wicket with Gunn. That summer of 1886 also saw three Test matches against Australia. Shrewsbury played a hand in each of the three victorious Tests, but the best was reserved for the second match at Lord’s.

On a rain affected wicket against a bowling attack including Fred Spofforth, Joey Palmer, Tom Garrett and George Giffen, Shrewsbury batted seven hours and was the last out for 164. The editorial note in Cricket observed, “Arthur Shrewsbury’s magnificent innings this week is eminently gratifying to those who believe in the survival of the fittest. Shrewsbury has been for the last two years undoubtedly the best professional batsman in the Country, and therefore his brilliant achievement in the great contest of the season, and against the Australian bowling, cannot fail to be particularly satisfactory to all who value the maintenance of our reputation on the cricket field.”

Shrewsbury scored 1,404 runs that summer and once again Nottinghamshire retained the title.

The Nottinghamshire professional led the team to Australia once again in 1886-87, winning the two low scoring Tests. He also scored 236 for the Anglo-Australian combined Non-Smokers against the Smokers in a match played at Melbourne, adding 311 with William Gunn. Financially, though, the tour was a failure.

The year 1887 was the crowning glory of this great batsman. He scored 1653 runs with eight hundreds at 78.71. It was the best ever average in a English season till then, beating WG Grace’s 78.25 set in 1871. In this particular summer, Grace was the second best in England with an average of 54.26. The gap between Shrewsbury and the next was really striking by now. During the season he enjoyed a sequence that ran 119, 152, 81, 130 and 111, and finally he finished the season with his highest First-Class score of 267 against Middlesex.

Cricket and Football Ventures

Shrewsbury toured Australia again in 1887-88. This time, however, it was a total disaster from the financial point of view.

The Melbourne Club was financing their own rival England team led by Walter Read and did not play their main cricketers against Shrewsbury’s side. The Victoria team contained only four front-line cricketers, and lost by an innings and 456 runs. Shrewsbury got 232 in the match, the first Englishman to score a double hundred in Australia.

The two English teams on tour combined to play a Test against the hosts at Sydney. England were led by Walter Read and won a low scoring game. Shrewsbury characteristically top-scored with 44.

On the tour, Shrewsbury scored 721 runs, 500 more than the next man. His average, too, was in the 60s. However, the numbers associated with the monetary losses were even more imposing. To try and recover some financial ground, Shrewsbury stayed back in Australia and managed an English rugby team.

The team, although not thoroughly representative, was a strong one. It was led by RL Seddon of Lancashire and Swinton. But, in a tragic accident, Seddon drowned while sculling on the river Hunter at Maitland. The captaincy was assumed by AE Stoddart, Shrewsbury’s fellow cricketer, and, later on, another suicide victim. The football team played 34 matches in Australia and 19 in New Zealand. However, the tour added to the losses, ending in a £800 deficit to add to the £2400 lost incurred on cricket.

The last years

Back home, Shrewsbury continued to score mountains of runs in the English seasons, and was chosen a Wisden Cricketer of 1890 — in the second year after the inception of the award. To perhaps celebrate the occasion, he hammered 267 against Sussex, equalling his best score and sharing a stand of 398 with Gunn — a second wicket record for the Notts that stands till this day.

He failed in the Tests against Australia, but Lord Sheffield offered him a place in the side for the 1891-92 tour of Australia. Shrewsbury declined, opting to stay back and manage his business, specifically because Shaw was travelling as manager of the team. However, his lordship picked his brains for the financial estimates of the tour and Shrewsbury sent him detailed calculations. He also cautioned the peer that all such figures would go for a toss if amateurs were included in the team. “I was told when in Australia that the expense of each amateur member of Lord Harris’s team was more than double of any one of the professionals …. Should Dr WG Grace go out, I should imagine, looking at the matter in a purely pecuniary point of view, that his presence would make at the very least £1,500 or £2,000 difference in the takings. It is probable it would exceed this amount.”

In the end Shaw informed Shrewsbury that the costs were much in excess of the estimates. The batsman retorted, “I didn’t know that Lord Sheffield had to pay for Grace’s wife and family expenses in Australia.”

That year, Shrewsbury coached at Edgbaston, and among his wards was Dick Lilley, later wicketkeeper-batsman of Warwickshire and England. Lilley later recalled the excellence of Shrewsbury as coach, as well as his insistence on travelling back to Nottingham each night. He hated to sleep anywhere but in his bed at the Queen’s Hotel. This gives us some vital insight into Shrewsbury’s character as well.

In 1892, Shrewsbury scored the tenth and final double century of his career against Middlesex. He scored four more hundreds that season and carried the bat for 151 for the Players against the Gentlemen.

The following year, 1893, saw him engage in another huge partnership with Gunn, 274 against Sussex at Hove. And after Tom Richardson’s pace had unsettled him against Surrey, and the pace had suggested that he was getting too old to play fast bowling, he responded with 148 against Arthur Mold of Lancashire.

When Australia visited that season, Shrewsbury scored 106 at Lord’s against Charlie Turner. Wisden reported: “Shrewsbury’s batting was marked by extreme patience, unfailing judgment, and a mastery over the difficulties of the ground, of which probably no other batsman would have been capable.” It was during this innings that Shrewsbury became the first Test cricketer to score 1000 runs. He added 81 in the second innings for good measure. He followed this up 66 at The Oval and ended his final Test series with 284 runs at an average of 71.00.

Shrewsbury missed the 1894 season because of health problems, but when he came back in 1895 he was once again on top of the country averages. And in 1896, he passed 1000 runs again, scoring two more hundreds He continued to make runs, egging on his ageing body with relentless practice. In he added 391 for the first wicket with young Arthur Jones, a county record that stood for 101 years.

And at the age of 46, Shrewsbury topped the season’s batting averages again in 1902, scoring four hundreds, including two in the same match. According to Wisden: “His batting was marked by all its old qualities, and except that he is, perhaps, less at home on a really sticky wicket than he used to be, there is little or no change to be noticed in his play. He was as patient and watchful as ever, and once or twice when runs had to be made in a hurry he surprised everybody by the freedom and vigour of his hitting.”

The Nottinghamshire Committee raised donations of £177 14s for the veteran in recognition of his batting performance.

That was the last season that he played. He finished with 26,505 runs from 498 matches at 36.65 with 59 hundreds. In 23 Tests, he scored 1277 runs at 35.47 with three hundreds. At the time of his final Test, no one had more runs or a better average in the short history of Test cricket.

The style …

EHD Sewell, who knew Shrewsbury during the last few years of his life, observed: “Little by little, this little man playing a quite different kind of cricket to any of the other Big Noises of his time, perfected his own chosen method: never heeding anything in the shape of advice or an adviser, until he became a kind of legend.” This ‘method’ was Shrewsbury’s celebrated back-play. While most of the batsmen of the 1870s and 1880s scored off the front foot, Shrewsbury concentrated on playing back, keenly following the ball till the last moment. This allowed him to master the very poor wickets still prevalent in county grounds. According to old Surrey cricketer William Caffyn, “Shrwesbury has always been the master of the grand secret of playing a totally different game when on a hard wicket to when on a soft and sticky one.” This ability, according to Caffyn, was the hallmark of a really great batsman.

Never very well built, Shrewsbury confessed that he did not quite hit the ball, but steered or stroked it to different directions. The bat seemed to be an extension of his body. His play was unconstrained and graceful. According to Wynne-Thomas, “Every swing and motion of the bat proclaimed a polished expositor of the fine art of cricket.”

There was a perception that he was a slow batsman, mainly due to his unwillingness to launch into big hits. However, as CB Fry pointed out, “Arthur has been very quiet, and a little monotonous, but somehow or other has scored almost as fast as other batsmen. Is not Arthur Shrewsbury the slowest scorer in England? Wrong: he scores just as fast as any other batsman who is not a professed hitter… he does not waste time and energy in banging ball after ball into fieldsmen’s hands. He waits and scores — waits and scores. Shrewsbury makes no fuss, and you think it is slow. This is a delusion. Runs are coming much at the same pace either way. If you go into the matter you will find it so.”

One of the few adverse comments about Shrewsbury’s batting was his use of pads as a second line of defence. Rait Kerr, in his book The Laws of Cricket, stated: “As we have seen the improvement in pitches have enabled Arthur Shrewsbury to develop a new gospel of defensive batsmanship … From about 1885, the technique involved an increasing use of pads, which in a year or two was causing the deepest concern in the cricket world and as a result the reform of the lbw Law became the question of the hour.”

… and the complex man

Shrewsbury the man was a complex character. That he was almost impossible to dislodge at the wicket underlined the intensity of his nature. He did take risks away from the game, as in his Shaw and Shrewsbury business and the Australian tour ventures. However, he was an accumulator by instinct.

His stubbornness at the wicket made him very similar to another later day professional, Geoff Boycott. There was one other similarity between the two batsmen — extended bachelorhood. He enjoyed a long relationship with Gertrude Scott, his girlfriend. The two ‘kept company’ for several years and one newspaper report also spoke of Scott as his fiancée. But they never got married.

According to his contemporaries, Shrewsbury was shy and retiring. As soon as a game was over, he was keen to return home. Even his fellow professionals claimed he did not mix freely with them. He was acutely sensitive of his baldness, which spread while he was still a young man. He was never seen without a hat. On the field he wore a cricket cap, and immediately on the completion of the day’s play, he would change it for a hat — preferably with no one noticing the sleight of hand. He quite matched the peculiarity of Clarrie Grimmett in this regard.

George Lyttleton, in a letter to writer and critic James Agate in 1944, disclosed, “Do you know a queer fact about Shrewsbury? No one saw him naked.” Agate’s retort was curt, “It hadn’t occurred to me that anybody would want to see Shrewsbury naked.”

Yet, in spite of his shy diffidence, at the age of 22 he was standing up for his rights as a professional cricketer against the bellicose Captain Holden. He was the leader of the strikes among Nottinghamshire professionals. And he had enough enterprise to flourish in his business, dealing with clients regularly, without any training, running Shaw and Shrewsbury almost single-handedly because Shaw stayed far away from the store.

The business letters show him to have been uncompromising and blunt. There is little evidence of a sense of humour, but plenty of hypochondria. One of his letters, dated 1900, proclaim, “Am pleased to say my health, as far as I know, is all right.” A few weeks after this letter was posted he declined to play in a mid-April match for fear of catching a cold or something worse.

There is no doubt that he trained religiously to keep himself fit and at his best as he grew older, but by 1899 the selectors had decided that both Grace and he were too old for the England side. The decision had more to do with tardy fielding than the batting. In his heydays, Shrewsbury had been a decent fielder, on some occasions taking catches while diving full length. However, by this time he had slowed down considerably. As England and Australia played at Trent Bridge, it was the first ever Test match at Shrewsbury’s home ground, and he had been left out of it. He watched the game alone and dismal, sitting in solitude under George Parr’s tree.

Another denting blow was the change of management at the Queen’s Hotel. In 1902, after 32 years, Shrewsbury was compelled to move out by the new landlord. He shifted into the house of his widowed sister at Trent Boulevard, and was hugely successful in the 1902 cricket season. But, soon after the end of the cricket for the year, he was stricken by sharp pain around his kidneys.

Doctors were consulted, but nothing untoward could be found. He spent some time in a nursing home in London, and then moved to the house of Amelia Love, another of his sisters, staying at The Limes, Station Road, in the village of Gelding. By 1903, he had missed the winter nets and was not really sanguine about playing county cricket that summer.

By his own hands

On May 12, 1903, Shrewsbury went into Nottingham and purchased a revolver at Jackson’s in Church Gate. He returned after a week, saying he could not fire the gun. It was discovered that he had bought bullets of the wrong calibre. The correct bullets were supplied. On the evening of May 19, he went up to his bedroom, asking his girlfriend Gertrude Scott to make him some cocoa.

While preparing the beverage, the lady heard a strange noise upstairs. When she called out asking whether everything was okay, Shrewsbury responded, “Nothing.” He had actually shot himself on the left side of the chest, and was still unsure about the result. Fearing that he had failed in his attempt, he placed the pistol to his right temple and pulled the trigger. Death was instantaneous.

On the morning of May 20, the news of the death was telegrammed to the Notts team. There was a game on against Sussex at Hove, the scene of so many of Shrewsbury’s triumphs. As a mark of respect the match was abandoned. The funeral took place two days after the death, and he was laid to rest at the Gelding cemetery. Among those present were William Gunn, Alfred Shaw, Wilfred Flowers, Mordecai Sherwin and other Notts cricketers and some from other counties as well. Shrewsbury’s 80-year-old father and three brothers were the principal mourners.

At the inquest, Gertrude Scott disclosed that on the afternoon before his death, Shrewsbury had said, “I shall be in the churchyard before many more days are up.” He had been convinced that he was suffering from some incurable disease. Wisden mentioned that it was a combination of this fear and an unhinged mind that had led him to the act.

Four years later, Alfred Shaw died of natural causes. He was buried in the Gelding cemetery as well. However, contrary to the urban legend, the distance between the graves of Shaw and Shrewsbury is not 22 yards but a few yards more. Some say it was to allow for Shaw’s bowling run up, and others offer the reason that it was because the relationship between the two had not been the best during the final years.

The Shaw and Shrewsbury firm supplied cricket bats around the world for 70 years since its inception. In1939, after the outbreak of the Second World War, it was closed down and the assets were bought by Grays of Cambridge.

For years, the cricketing world suffered from the absence of a biography of this great Nottinghamshire and England batsman. There were a couple of obscure pamphlets and a work by WF Grundy published in 1907 with the title, Memento of Arthur Shrewsbury and Alfred Shaw, Cricketers — the last mentioned a collection of obituary notices and tributes. This glaring gap was filled by Peter Wynne-Thomas, archivist at Trent Bridge and Secretary of the Association of Cricket Statisticians, who wrote the long awaited story of Shrewsbury’s life. It was published it in 1985 and was titled — what else, but — Give Me Arthur.