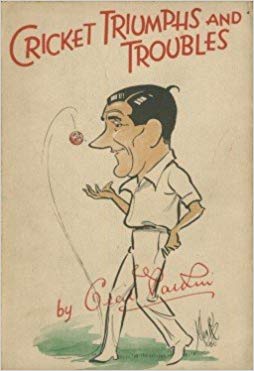

Cecil Parkin, born February 18, 1886, was a bowler with an unlimited bag of tricks who could send down every kind of delivery. Arunabha Sengupta remembers the conjurer whose career was tragically cut short due to some ill-advised column in the press.

The course of genius never did run smooth. And thus was charted the tale of Cecil Parkin.

He was a true conjurer. His bag of tricks as a bowler was bottomless. He is generally jotted down in player profiles as an off-break bowler, probably because that is the closest approximation to what he did most often. He ran in at formidable pace in his early years, and it remained more than medium as time went on adding layers of age to his waistline. He could bowl all varieties of balls, several his own inventions, and often attempted to send down his entire repertoire during the course of a single over.

Between deliveries he would keep the crowd enthralled. He was always juggling the ball, palming it under the nose of the umpire, hiding it in his pocket. He kicked it up with his boots and caught it with nonchalance, a gimmick many a kid tried to copy. Often beating the bat with mysterious manoeuvres that left the batsmen looking embarrassed and the crowd laughing their hearts out, he followed it up with a word for his colleagues and the opposition. He was the bowler the crowds came to watch.

When back in the pavilion, he delighted his professional colleagues with jokes, tales and virtuoso feats with a deck of cards.

He was an entertainer to the core, a jester who was also one of the best bowlers in England. According to RC Robertson-Glasgow, “He enjoyed fantasy, experiment and laughter. He loved cricket from top-to-toe, and he expected some fun in return.”

And sad is the jester whose eyes lose the glimmer of fun. This ebullient man saw his England career peter out in a complicated saga of misfortune, and did not have the heart to carry on playing in the county game.

Like many a northerner, Parkin had no time for diplomatic niceties. Often the columns he wrote for the press during his playing days had the traditionalist in Lord Hawke frothing at the mouth.

But, even if such liberties were excused, his ultimate castigating criticism of England captain Arthur Gilligan was way too much for the establishment to tolerate. “I feel unwanted,” he declared and moved away from Lancashire CCC. He had promised himself seven full county seasons, but had to do with just four.

A self-taught bowler

Parkin was born at Egglescliffe, where his father worked in the railways. By the time the family moved to the idyllic Norton village to the north of Teesside, Parkin senior had been appointed the station master. The hissing locomotives captured the boy’s imagination, but at the same-time there was a greater attraction. From the window of his room, he could gaze at the Norton-on-Tees cricket ground.

Even as a twelve year old, Parkin was included in the team of serious Norton cricketers based on his enthusiasm alone. He did not bowl, batted at No 11, but chased every ball in the outfield like a hare. As he raced about, he was watched from the boundary bench by Charlie Townsend.

At 16, he was an apprentice pattern-maker. And at the same age, he was overjoyed at getting a call from North Ormesby of the North Yorkshire and South Durham League.

His father said he was too young ‘for any of that nonsense.’ Young Parkin did not relish the objection, but he was confident he would be called again. He practised hard at Norton club, working on his batting.

And at 18, he passed a successful trial with Ossett as a batsman. He was asked if he could bowl. He had no idea, and so he said, “Aye, and take a few wickets for you.” His instruction in the art of bowling had been watching Townsend from a distance. In any case, he ran in from wherever his fancy took him, bowled quickish, and captured 116 wickets for Ossett that summer.

According to Parkin, he was really fast. The great Yorkshire professional George Hirst, and coach Harry Haley, had come to take a look at him. Supposedly, on witnessing his speed, both Hirst and Haley decided against putting on the pads and facing him. The story is most probably a figment of Parkin’s rich imagination. Hirst, after all, would score 2,385 runs and pick up 208 wickets that summer, and it is difficult to imagine him refusing to face a rookie bowler. However, the duo did recommend Parkin for a county game.

A few yards off Yorkshire border

Parkin played only one game for Yorkshire. It was against Gloucestershire at Headingley in July 1906. In a rain interrupted match, he took two for 23 from eight overs. Hirst and Wilfred Rhodes watched him with evaluating eyes as Schofield Haigh shouted encouragement.

ACCORDING TO PARKIN, HE WAS REALLY FAST. THE GREAT YORKSHIRE PROFESSIONAL HIRST, AND COACH HARRY HALEY, HAD COME TO TAKE A LOOK AT HIM. SUPPOSEDLY, ON WITNESSING HIS SPEED, BOTH HIRST AND HALEY DECIDED AGAINST PUTTING ON THE PADS AND FACING HIM

However, there was the enquiry kicked off by that President of Yorkshire, Lord Hawke. It was revealed that Parkin had been born a few yards on the other side of the Yorkshire border, in Durham. Hawke, whose birth certificate betrayed native allegiance to Lincolnshire, was a fanatic about these details. Parkin came to know he could not play for the county again. His Second XI captain bid him goodbye, handing him a recommendation that said that Parkin was a “born cricketer, a very good man to have on your side, a pleasant cheerful fellow.”

Yes, Parkin was cheerful. For him cricket was fun. He decided that fun was for spinners. He had looked at many a fast bowler and had found them grim and grumpy. Hence he turned his hand to the vagaries of spin and trained assiduously.

Following the footsteps of the great Sydney Barnes, whom he watched and admired, Parkin started playing club cricket. He spent three years in Staffordshire, playing for Tunstall. He used his many hours of spare time to perfect his spinners, turning them from off to leg and leg to off. He was entirely self-taught. Helping him perfect his spinners would be his dear and faithful wife.

She stood bat in hand, stopping the balls, often beaten by the turn and struck painfully on the thigh or arm. But, the good lady stuck to her task, and by induction so did Parkin. The art of spin was perfected.

However, on the playing field, he stuck to medium pace. Parkin soon started playing for Church, and picked up more than 100 wickets in every season but one up to 1915. In 1914, he missed 7 matches due to injury and finished with 91.

Lancashire calls

There were two matches played against the Lancashire County club. He took six wickets in each. However, he was rejected after being considered too thin. He was over six foot tall, but weighed under nine stone. It was assumed he would be wanting in stamina. Parkin bristled at this reason for rejection and continued to take wickets in the league.

And finally, during a match against Leicestershire in Liverpool in 1914, Lancashire found themselves short of players. An SOS was sent to Church to release Parkin. The bowler was 28 by then. He was on his way to recovery from a broken ankle. But he did not hesitate to play.

The Aigburth pitch was heavily saturated with rain. Breaking the ball both ways at a brisk pace over medium, Parkin bowled 51 overs in the match, taking 14 for 99. Cecil Wood, comically foxed by a quick turner, knocked all three stumps with his bat in a fit of temper. It was a story Parkin would recount all his life.

He played in 6 matches that season, missing the weekend encounters because of the League. His haul of wickets was 34, and he ended up leading the Lancashire averages. And then there was the War.

Parkin spent the First World War as a fuel overseer in Oswaldtwistle. On Saturdays he played for Undercliffe in the Bradford League. The side also featured South African cricketer Charlie Llewellyn and the Nottinghamshire stalwart, George Gunn.

Test cricket

When cricket restarted, Parkin was held in the highest of regard. Rex Pogson observed in The County Cricket Series that between the wars he was probably inferior only to Maurice Tate as a fast-medium bowler. “If he had been content to be one of the best fast-medium bowlers of his day he might have been more successful than he was, but he would not have been Parkin.”

After the War, Parkin was signed by Rochdale in the Central Lancashire League. Apart from a weekly salary, he was promised a £100 benefit and £20 backhander for signing. It was quite unheard of in those days.

In June 1919, he was released by the club to play the Whitsun game against Yorkshire at Old Trafford. With matches limited to two day duration, Parkin won the game with seven minutes to spare. His figures were 6 for 88 and 8 for 52. A succession of Yorkshiremen surveyed their disturbed woodwork, or watched helplessly as their offerings were snapped up by one of the three close-in fielders on the leg side. “Hey Ciss, what you been doin’ to theet ball, lad?” some asked. “Don’t blame ball, son. Ee, it was you, not ball,” Parkin responded.

When he went down to play against Gentlemen for the Players at Lord’s and The Oval, the papers announced, “Parkin arrives in town.”

It was the 1920 fixture at The Oval which proved pivotal. The Gentlemen, batting first on a good wicket, were all out for 184. Parkin claimed 9 wickets, 6 of them bowled. AW Carr was fooled by a slower ball while Percy Fender was done in by a lightning quick yorker. He also played 5 matches for Lancashire that season, picking up 39 wickets.

The performances earned him a trip to Australia. On that ill-fated tour of 1920-21, Parkin joined the party of John Douglas and played for England for the first time. He did not exactly do great things Down Under. The great Australian batting line up, with Warwick Armstrong, Charlie Macartney, Herbie Collins, Warren Bardsley, Charles Kelleway and others may have intimidated him. His 16 wickets came at 42 apiece. However, there was enough excitement.

At Adelaide, Jack Hobbs hit a hundred and Parkins took 5 for 60. During the lunch interval, a messenger came to the dressing room announcing that the State Governor would like to see the great batsman. When Hobbs returned, he was beaming. He had been presented with a diamond scarf pin.

Parkins was not amused. “The batsman always gets the reward. What about the poor bowler?”

The message was somehow passed to the State Governor. Soon the messenger arrived again, this time asking for Parkin. The thrilled bowler was out of the door before the message was delivered in full. The military band played a few stirring bars from an overture as he approached. Parkin rehearsed an impromptu speech of acceptance. But, the only thing the Governor said was, “ell done, Parkin.” There was no diamond scarf pin.

“Nowt,” exclaimed the furious bowler when he got back to the dressing room. “I’m telling you I got nowt.”

Jack Hobbs nodded, “Bad luck Ciss, but you did choose to be a bowler, not a batsman.”

An elderly lady in the stands was more generous. She gave Parkin a basket of fruit. The apples were pinched by his teammates, and probably one of them was shied from the boundary line instead of the ball by Patsy Hendren.

Returning to England, Parkin was at the top of his form, taking wickets by the bushel in the league and the few county matches he played. The spinning fingers now worked more furiously, adding guile and skill to his deliveries. When Armstrong’s men arrived he played in all the Tests but in Nottingham. The 16 wickets in the series came at 26.25, including 5 for 38 at Manchester. That match also saw him sent in to open batting in the second innings, thus achieving the distinction of opening the bowling and batting in the same Test. His only regret remained that none of the nine Tests against the Australians ended in a win.

The explosive column

In 1922, Parkin left Rochdale and concentrated on county cricket for Lancashire. His haul of wickets was 172 at 16.50. The next year, he took 209 wickets in all, 176 of them for his county. Tate was the only other bowler in the country to pass 200 wickets, beating him to the landmark by two hours.

Against Glamorgan, he took 15 for 95 at Blackpool. When the Welshmen came over to Liverpool, he took 10 more, including 5 without conceding a run. His figures for that innings read 8-5-6-6.

By this time, however, he had also been ruffling a few feathers. He wrote an often ghosted column for Empire News and his views were not quite as tempered as a discerning professional’s should have been. He queried pointedly, “Why not Herbert Sutcliffe, why not Jack Hobbs?” And the establishment shuddered. Parkin had asked the tabooed question — why couldn’t a professional lead England? Lord Hawke was on the verge of apoplexy. In a long speech at the next annual meeting of Yorkshire County Club, His Lordship rebutted the arguments, ending with the infamous words, “Pray God no professional will ever captain England.”

Parkin was unapologetic. “No one has been more content to play under amateur captains. But amateur skippers should be capable of holding their places on their merits as players. I still say that if such men were not forthcoming, England should choose a professional captain. I was surprised Lord Hawke adopted the attitude he did.”

That storm blew over, but another did not. A day after the anniversary of Parkin’s wedding, on June 14, 1924, England met South Africa at Edgbaston. It was the debut of Sutcliffe, Tate and Percy Chapman. It was the first time Hobbs and Sutcliffe started an innings for England, adding 136. The home team scored 438.

In response, South Africa were all out for 30. Captain Gilligan and Tate bowled unchanged. The skipper finished with 6.3-4-7-6. Tate with 6-1-12-4.

Following on, the tourists batted again. They fared much better this time around. Gilligan and Tate again took nine wickets between them, but the final score was 390.

Parkin, in the middle of a tremendous season, at the top of national averages, was brought on almost as an afterthought. He bowled 16 overs without success, conceding 38 runs. Later he confessed that the wicket was hard while he preferred softer pitches.

But on that day he was furious. He was being ignored by Gilligan. Several people, some of them in the pavilion, were laughing at him. After the match, Parkin and 12th man Ernie Tyldesley booked a taxi to go to the station. As they got in the cab, Gilligan approached and shook hands with Parkin. “Sorry you haven’t bowled much today Ciss,” the captain said. “I hope you’ll get some sticky wickets soon.”

They parted on good terms. But a few days later there was an explosion in the press.

In the sports pages of Empire News a headline announced, “Cecil Parkin refuses to play for England again.”

The article, written under Parkin’s name, read: “On the last morning of the Test match there were 105 minutes of play. With Catterrall hitting so finely, it was necessary for the England captain to make bowling changes. During those changes I was standing all the time at mid-off, wondering what in earth I had done to be overlooked. I can say I never felt so humiliated in the whole course of my cricketing career. Nothing like it has ever happened to me in First-Class cricket … I can take the rough with the smooth but I am not going to stand being treated as I was on Tuesday. I feel that I shouldn’t be fair to myself if I accepted an invitation to play in any further Test match. Not that I expect to receive one.”

The cricketing establishment was shocked. And so, it is claimed, was Parkin. Later he disclosed that a cable had reached him from the newspaper office asking for his column. Being rushed, he had asked a Lancashire pressman to send an article on his behalf. He had not reviewed the piece.

Whatever be the case, Parkin never played for England again. His letter of apology to Gilligan was accepted with a fine, kind gesture, but the England selectors were not prepared to consider him anymore. This sort of sensational material was not something that the game’s hierarchy relished reading on a leisurely Sunday morning.

There are reports that not only was Gilligan wise in keeping him away from bowling on a hard wicket, but Parkin was not fit enough to roll his arm over. In his autobiography, EJ ‘Tiger’ Smith wrote: “Parkin had an injury in his arm and back, and the Aston Villa trainer was summoned to massage him.” Parkin never mentioned the injury. Neither did he ever disclose the name of the ghost writer who penned the damning article.

Last days

Parkin lost the appetite for infectious joy that had been the source of sustenance for his game. He faded away from the county circuit. The great Australian Ted McDonald had joined Lancashire and had taken over the mantle of the star attraction. Parkin moved away from the county scene.

His 10 Tests had got him 32 wickets at 35.25 apiece. In First-Class matches, his tally was 1048 at 17.58.

In 1927, Parkin joined Blackpool, opened a hotel and played as an amateur. Blackpool won the Ribblesdale League, and Parkin scalped 138 wickets. He went on to East Lancashire as a pro at Blackburn before moving to Tonge in the Bolton League. He was a Levenshulme professional in 1935 when gout intervened, effectively ending his cricket.

In his later days, Parkin ran pubs and regaled customers with cricketing tales. He put on weight, nearly seventeen stone by the time he played his last for Tonge. By then, he bowled leg-breaks and googly. His son Reg Parkin was an all-rounder who played 20 matches for Lancashire.

Cecil Parkin passed away at Manchester at the age of 57. He had been afflicted with throat cancer. Hirst, Rhodes and Harry Makepeace attended his funeral at Manchester Crematorium and the ashes were scattered over the wicket at Old Trafford.

Neville Cardus reported that Parkin’s wife had laid a red rose on each end of the wicket. But then, Cardus, Lancashire and romanticism is a combination that allows for little verifiable fact.

However, the master writer was decidedly more accurate when he described Parkin on the cricket field: “Who indeed was Cecil Parkin? He was one of the greatest right hand off-breakers I have seen anywhere … On a turning pitch he was unplayable. I used to watch him from behind the bowler’s arm. On his day I used to imagine that he was attacking any great player I had ever known — Ranjitsinhji, George Gunn, Fry, Trumper, Macartney. And I could not think of any sort of science or skill by means of which they could have survived against Parkin.”