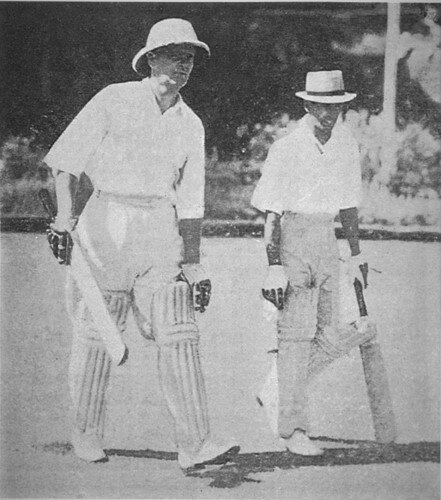

Conrad Powell Johnstone. Archival image

by Pradip Dhole

Roots

It seems that the origin of the name Madras is shrouded in a conflict of theories. Shreekumar Varma, in his article Madras in Words, postulates, among others, two interesting theories, one based on historical fact, and the other out of the great Indian epics.

One story involves Vekatappa Naik, also known as Naik Venkatadiri, a rather whimsical man of means, who, in Aug/1639, had granted the ownership of the small coastal village, absolutely free of cost, to the British agent Francis Day for the purpose of constructing what would later come to be known as Fort St. George, a veritable bastion for the British presence in the south of colonial India. It seems that the only favour that Naik had sought was that the British establish a town on the land and that the town be named after his honourable father, Chennappa Naik

The postulate continues that the British had subsequently named the new town Chennapattnam ("Pattnam" or "pattinam" means "town" in Tamil). At a later date, the name had been shortened to Chennai. The local people had not been very amused at the development, particularly with the influx of the British into their very own back yard, as it were, and had begun calling the eccentric benefactor the Mad Rasa, or the mad king

The other reference is to the great Indian epic, the Mahabharata, where there is mention of a queen of King Pandu named Madri, supposedly born and brought up in the south of India, the region then being known as Madra-raj or Madra-desh. The inference hinted at is that the above-named queen may have been the inspiration behind the name of the region, although the connection appears to be somewhat teleological and tenuous.

The truth of the matter may never emerge from the distant pages of history with any degree of authenticity or conviction. Suffice it to mention, then, that the capital city of the Madras Presidency, as established by the British, came to be documented as Madras. But history has an interesting habit of updating recorded facts, and it was on July 17 1996, that Mr. M. Karunanidhi, one of the grand old men of Tamil Nadu politics who have very rightly passed into the Valhalla of Indian politics, and the then Chief Minister of the state, made the announcement in the State Assembly that the state capital Madras would henceforth be officially known by the name Chennai in all languages, thus putting an official stamp on the nomenclature of the city

Whatever be the legend associated with the origin of the moniker, it is an undeniable fact that cricket had begun to establish its presence in Madras following the arrival of the Union Jack, the story being true all over the world, and in all the countries that the British had thought fit to colonise. Initially restricted to only the military personnel, the charm of the game had soon also held even the Imperial civilians in its thrall. As the game had gained a firm foothold in southern India, various clubs were formed, primarily by the British for the benefit of the expatriate population.

The vanguard of the local cricket enthusiasts, led by stalwarts like Buchi Babu Naidu, of hallowed memory, soon followed suit, and by the turn of the 19th century, cricket had been firmly anchored in southern India. One of the defining events in the development of cricket among the local population of Madras had been the establishment of the Madras United Cricket Club, later known as the Madras United Club by Buchi Babu in 1888.

Madras soon became a busy hub of local club cricket, surprisingly well organised for the times, and perhaps the best structured in the country, competing in various tournaments for a variety of shields and trophies, with legendary teams from the likes of the Mylapore Recreation Club, Triplicane Cricket Club, Madras Cricket Club, Alwarpet Cricket Club, Jolly Rovers Cricket Club, the cricket club associated with the State Bank of India, among others, adding a local flavour to the tenor of Madras cricket.

The young Johnstone

Meanwhile, while all the busy cricketing activity in connection with the gradual evolution of cricket in southern India was taking place in the Madras Presidency, a rather more commonplace event was underway almost halfway across the world, in Sydenham, a south-eastern borough of London County, bordering on Kent. A male child was being brought into the world in the household of William Johnstone, a “gentleman of independent means”, and his wife Katherine, on 19 Aug/1895. Christened Conrad Powell, the child was more popularly known as “Con” Johnstone.

Learning his three R’s at Hartford House School, Con Johnstone received his formal schooling at Rugby from 1912 to 1913. Cricket bloomed in the young Johnstone’s life while he was at Rugby, the schoolboy gradually developing into a forceful left-handed batsman, and a right arm medium-paced bowler of genuine merit. In all, he played 6 second class games for Rugby, captaining the school cricket team in his second year, and also playing in the racquets pairs.

Playing for the Public Schools against the MCC at Lord’s in Aug/1913, Johnstone had a solid 50 in the 1st innings. He had 3 “Minor” games for the Kent Second XI in the Minor Counties Championship in July/1914 before embarking on the next step up in the education ladder, at Pembroke College, under Cambridge University, from late July/1914 as a promising 19-year old all-round sportsman

The Great War

The outbreak of World War I put his education, and his cricket career, on temporary hold for the duration of hostilities. Johnstone volunteered his services for the War in Aug/1914. The SUPPLEMENT TO THE LONDON GAZETTE, 26 NOVEMBER, 1914, shows the following entry: “Conrad Powell Johnstone, 3rd Battalion, Highland Light Infantry. Dated 25th September, 1914.” His military career stretched to 1919, with service mainly in France with the 17th Battalion of the Lancashire Fusiliers. During the War, he suffered a bullet injury in May/1915 that broke two ribs and perforated a lung. He later also took a bullet in the neck.

In Oct/1917, he was wounded again, this time by a shell explosion. After a period of recuperation, he was deemed to be fit for Home Service and spent the rest of the War as an instructor with the 6th Officer Cadet Battalion in Oxford till the end of the global conflict, finally putting in his service papers in May/1919.

Con Johnstone thought it fit to go back to Cambridge in 1919 with his War gratuity to study for a Law degree. He was able to graduate in 1920, having had the benefit of being credited with four terms of study on the strength of his War record. While at Cambridge, he pursued his two great sporting loves of cricket and golf. Johnstone was an immediate success in the first of the Cambridge University Trial games, playing for the Perambulators against the Etceteras in a second-class game from 15 May/1919. Opening the batting in both innings, he had scores of 84 and 17, and had bowling figures of 4/46 in the 1st innings. In the second Trial game from 10 May/1920, and playing for a Cambridge XI against a XVI of Cambridge University Next, Johnstone scored 101 and 11.

Post War

Johnstone made his first class debut playing for Cambridge University against the Australian Imperial Forces at Fenner’s from 21 May/1919. The undergrads lost the match by an innings and 239 runs, with debutant Johnstone scoring 23 and 12. The match was dominated by centuries from the bats of visiting skipper Charles Kelleway (168) and “Nip” Pellew (105*), and the bowling of Jack Gregory (6/65 in the 1st innings) and Cyril Docker (5/41 in the 2nd innings).

He did fairly well in his first match against the traditional rivals, Oxford University, at Lord’s from 7 Jul/1919, although Oxford won the match by 45 runs. Johnstone had a 1st innings score of 78, sharing a 1st wicket stand of 116 with ‘keeper George Wood (62), who would later play 3 Test matches for England. Con Johnstone passed the landmark of 500 first class runs during this match.

He played 20 first class matches for Cambridge in his two years as an undergraduate, scoring 1082 runs at 33.81, with a highest of 106 (against the Army, in his second match for Cambridge), and 6 fifties. He held 22 catches for his alma mater. His 8 wickets came at 54.25. He earned his cricket Blue, adding a Blue for golf, captaining the golf team in a victory against Oxford in 1920.

Johnstone’s county debut came in his first year at Cambridge when he turned out for Kent against Hampshire at the Neville Ground, Tunbridge Wells (later to be the venue of a majestic 175* by Indian skipper Kapil Dev against Zimbabwe in the Cricket World Cup of 1983, when the game seemed to be slipping out of India’s hands), from 18 July/1919. This game was also Johnstone’s first class debut for Kent, along with wicketkeeper George Wood, who was also making his Kent debut. In a drawn game, Johnstone opened the batting in his only innings, scoring a modest 23.

Having graduated from Cambridge, and armed with his Law degree, Con Johnstone, like many other young and ambitious men of his generation, decided to throw in his lot with the other British expatriates in far off India in the hope of making a name for himself, and, perhaps, also a fortune. It is reported that he had arrived on the shores of southern India in late 1920 and had first sought a position in a liquor manufacturing concern.

His cricket profile shows a gap in his career from the last week of Aug/1920, when he had played for Kent against Middlesex at Lord’s, and early June/1925, when he is seen to have played for the Free Foresters against his old university at Fenner’s. Considering that he had registered a pair in the game, it may be said that the long lay-off may have had deleterious effects on his cricketing skills. It is possible that during this time Johnstone had concentrated on making a career for himself.

Con Johnstone and his bride in 1925

Kitty and her sons

While he may not have been very satisfied with his performances on the cricket field around this time, Con Johnstone was to have a very rewarding experience. He was smitten by the charms of a young lady from Wallasey by the name of Kitty Read Birchall, born in 1901. They were married at Wallasey in 1925, and raised two sons, Antony Conrad, popularly known as Tony, born in Aug/1926, and David Powell, born in 1930. Incidentally, both the sons were born in erstwhile Madras. The narrator is indebted to Lucie Unitt (nee Johnstone), grand-daughter of Con Johnstone, and daughter of the elder son Tony, for the details of the Johnstone family that she had helped the narrator with through personal communication. She has also very graciously sent the wedding photograph and has identified the other photographs.

Biographic notes on the career of Johnstone indicate that he had spent the summer of 1925 in England, honing his cricketing skills once again, and trying to pick up the threads of his cricket career. Turning out for Kent in 12 first class matches in the season and one game for the Free Foresters as mentioned above, he scored 524 runs at 23.81, with a highest of 102 against Gloucestershire. He was back in India over the 1925/26 winter, this time in the employ of Burmah Shell, a petroleum giant in south-east Asia of the times, and was stationed in Madras.

Kitty in her later years

Indian Winters

He was caught up in the first class cricket ambience of Madras almost immediately, turning out for the Europeans in the Madras Presidency match against a team named India at Chepauk, Madras, from 13 Jan/1926, and played over the popular Pongal festival of Madras. In what was to be his first ever first class match in India, Johnstone scored 135 in the 1st innings sharing a 7th wicket stand of 166 runs with Bob Carrick (107). His Kent interlude in 1925 was beginning to pay dividends. The Europeans won the match by 66 runs. He was to continue representing the Europeans in the same Pongal fixture till he left Indian shores in 1948.

One of the interesting facets of the match between the Europeans of the East and Arthur Gilligan’s MCC team at Eden Gardens from 26 Dec/1926 was the presence of one of the all-time legends of English cricket, Wilfred Rhodes himself, this time in the long white coat. Johnstone was in the thick of things, top scoring with 35 in the 1st innings, although the MCC won the match by an innings and 55 runs.

In his 28 years in India, Con Johnstone played 20 times for the Europeans, scoring 1257 runs in his forceful left-handed style, usually batting in the upper order, at an average of 35.91, his only century being the 135 that he had scored in his very first-class match in India, as stated above. He added 8 fifties to his tally and held 30 catches, usually close to the wicket. His right-arm medium-paced bowling for the same team netted him 59 wickets at a creditable average of 21.74 with best figures of 6/65 against India in the Pongal Madras Presidency match of Jan/1927, this particular performance being the first of his 2 five-wicket hauls for the Europeans.

Johnstone’s reputation gradually grew to iconic proportions, both with Burmah Shell and in Madras first class cricket, till he became one of the acknowledged pillars of the local team. Apart from his contributions with the bat and ball and in the field, and his uncanny leadership and organisational skills, another major influence that Johnstone had on local cricket in Madras involved his association with Burmah Shell.

He made it his mission to look around the profusion of club cricket being played in Madras at the time and to spot budding talent. On the strength of his reputation at Burmah Shell, Johnstone began to gradually add several young cricketers of promising talent to the workforce of the company, so that the youngsters could concentrate on furthering their cricketing skills without the worry of making a living. One of his protégés was Morappakam Josyam Gopalan, more popularly known as MJ Gopalan.

The slim, bright-eyed youngster, barely having graduated from Kellet High School in Triplicane, where his family had settled after relocating to Madras from Chingleput, and born in a relatively poor Iyengar family of Brahmins, having several noted astrologers in their ranks, was spotted rather early by Johnstone, by then the local Manager of Burmah Shell.

Although Gopalan had initially joined the ranks of the Madras Police, Johnstone ensured that MJ, as he was later to be called in Madras cricket circles, was soon under the banner of Burmah Shell. Stories are told of the young recruit of the company cycling from one petrol pump of the Company to another in the mornings, his duty being to measure the level of petroleum in the tanks and to make a note in his register before proceeding to the next. MJ Gopalan was to later play a stellar role in a path-breaking first class match of India.

In the summer of 1929, Johnstone was back in England and playing 8 matches for Kent against various opponents, and 1 for the MCC against Oxford University. The winter of the same year, however, found him back in India and participating vigorously in the Pongal encounter with India.

In the chronological course of events, it is, of course, common knowledge that the chequered history of Test cricket had been set in motion at the Melbourne Cricket Ground with a confrontation between representative teams from Australia and England from the Ides of March of 1877, the match enjoying the status of being the first ever Test match played. The third entrant into this brotherhood turned out to be South Africa when they first locked horns with a touring England team at Port Elizabeth on 12 Mar/1889.

The 20th century was well on its way when a conglomerate of cricketers from the Caribbean Islands, under the banner and style of West Indies, played England at Lord’s from 23 Jun/1928, becoming the 4th entrant into the exclusive club of Test playing nations. It was again at Lord’s, on 25 Jun/1932, that India achieved the honour of becoming the 5th member of the Test playing club, playing only 1 Test match in that particular series.

The arrival of an MCC side in the winter of 1933/34 under the controversial Douglas Jardine, of Bodyline infamy, paved the way for India’s second Test match, this time played on home soil at the Bombay Gymkhana Ground, from 15 Dec/1933. The match turned to be the first of three on the Indian leg of the tour, the others being played at erstwhile Calcutta and Madras. England won the first and third by handsome margins, whilst the second was drawn.

In addition to the Tests, the MCC played first class matches against regional teams. The game against Madras was played at Chepauk from 3 Feb/1934. Madras, led by wicketkeeper Humphrey Ward, went down by an innings and 352 runs, the large margin being ensured by centuries from opener Fred Bakewell (158) and Yorkshireman Arthur Mitchell (162). “Father” Marriott (5/43 in the 2nd innings, including a hat-trick) did his bit, with 3 more wickets in the 1st innings. Among the Madras players, only opener Johnstone stood out, top scoring in both innings with 46 (out of 106 all out) and 69 (out of 145 all out), going past the landmark of 3,500 first class runs in the game.

Although Johnstone had had some experience of captaining a first class team in the past, spinning the coin for Cambridge University, Kent, the Europeans, the MCC, and one game for Madras, all between 1920 and 1933, he was to achieve iconic status at Chepauk in this context on 4 Nov/1934.

In the meantime, cricket in India was gradually coming of age, helped in its evolution by the presence of the British military, expatriate British nationals and, especially in an around erstwhile Bombay, the Parsee community, who took to the game rather early. Passing successively through the phases of the Bombay and Madras Presidency matches, followed by tournaments competed for by teams based on religious affiliation in the form of the Bombay Triangular, Quadrangular, and later, the Pentangular tournaments, when a team of assorted religious followers named the Rest joined the fray, first-class cricket was gradually forming its own niche in the sporting history of India.

Ranji Trophy

It was a meeting held in Shimla in July/1934 that changed the profile of Indian first class cricket in one fell swoop, as it were. The top brass of the Board of Control for Cricket in India (BCCI), formed in Dec/1928, decided that, instead of allowing first-class cricket in India to be divided along religious lines, it would be far better to organise a National Championship of Cricket based on regional affiliation along the line of the County Championship. The basic format of the tournament was worked out, and the Maharajah of Patiala, Bhupinder Singh, claimed the privilege of donating the rolling trophy, to be named after the first Indian to play Test cricket, the Jamsaheb of Nawanagar, His Highness, Kumar Ranjitsinhji.

It had reportedly rained heavily on the evening of 3 Nov/1934 in Madras, casting doubts in the minds of local cricket aficionados about the feasibility of the historic match beginning at the scheduled time on the morrow, and the pitch had still been damp from early morning drizzles at Chepauk when Major Mark Teversham, almost 40 years of age and born in what is now Myanmar, captain of the Mysore side, playing his only first class match, and Con Johnstone, the Englishman born at Sydenham, England, and now captain of Madras, went out for the first ever toss of coin in the history of Ranji Trophy cricket. Winning the toss, Johnstone, the home skipper, with vast experience of local conditions, opted to field first. Naturally, all 22 players were making their respective Ranji Trophy debuts in the game.

There were five white men in the Mysore team, skipper and wicketkeeper Teversham himself, opener McCosh, and playing the first of his 2 first class games, as was the other opener, N Curtis, Cedric Buttenshaw, born in Nova Scotia, Halifax, and playing his only first-class game. The other white man in the team was the 29-year old Renshaw Nailer, born in Madras, who had played for Madras before joining the Mysore ranks. Nailer was a more distinguished player, and was to finally aggregate 1411 runs from his 33 first-class games. There were contemporary media reports of his off-drive being reminiscent of the great Wally Hammond’s.

It was 11:00 AM on 4 Nov/1934, when the Mysore openers, Curtis and McCosh, strode out to open the batting. Curtis faced the first ever ball in Ranji Trophy history, bowled by Johnstone’s protégé, MJ Gopalan, a quickish in-swinger, to go by contemporary media reports. It may be noted here that Gopalan was the only player on either side with previous experience of Test cricket, having played in the Test against England at Calcutta in Jan/1934. Bowling the first over from the other end was the legendary slow left arm orthodox bowler and hard-hitting left hand batsman, AG Ram Singh.

It turned out to be a massacre of the innocents. Ram Singh, bowling unchanged through the innings, had figures of 6/19 from his 13.2 overs. First change bowler, skipper Johnstone had figures of 4/10 from his right arm medium paced variations. The innings lasted only 27.2 overs, and there were five ducks recorded in the innings. The shining lights of the Mysore batting turned out to be opener Curtis (15) and Nailer (14) in an all-out total of 48, the first double-digit team score in the National Championship. Home ‘keeper SVT Chari effected 3 stumpings, and Cotar Ramaswamy, who was to become India’s second double International with his proficiency at lawn tennis, held 4 catches.

The batting performance of the home team was not much better, however, and they were dismissed for 130 in 43 overs. There were three men in the 20s: NN Swarna (22), Ramaswamy (26), and Gopalan (23). The wrecker in chief for Mysore was MG Vijayasarathi, 5th in the bowling sequence (6/23 from his 8 overs from his right arm medium paced off-breaks) who later went on to become a highly respected International umpire, and Treasurer, Vice-President, and President of the Karnataka State Cricket Association (KSCA). To the delight of trivia hunters, MG Vijayasarathi had once umpired in a first-class game in India along with his son, MV Nagendra (in a Ranji Trophy match between Andhra and Mysore at Bangalore in the 1960/61 season, becoming the 4th father-and-son pair to umpire a first-class match together in history).

The Mysore openers were back at the crease in the third session of play on the first day of the match. The story, alas, was no different for the Mysore side in their 2nd innings. The innings folded up for 59 in 30.3 overs, with only three men in double figures: T Murari (11), skipper Teversham (11), and Safi Darash, later to become a noted cricket commentator (10). Once again, Ram Singh proved to be the principal thorn in the side for the visitors, with figures of 5/16 from his 14.3 overs, once again bowling through the innings. Gopalan (3/20) and skipper Johnstone (2/10) added to the misery of the Mysore team.

The humiliation of the visiting team had been completed in only 100.5 overs, the scheduled three-day game being over in one day, with Madras emerging winners by an innings and 23 runs, the first instance of a Ranji Trophy match being completed in one day (the other being the Saurashtra v Baroda match at Rajkot on 5 Dec/1959). It must be stated, however, that the latter match mentioned was not played out to a conclusion, Baroda winning on a concession, following the demise of Maharajshree Duleep Singh, many of the participating players in the match being related to the deceased.

Several records were set in the game: Con Johnstone became the skipper to win the first Ranji Trophy match, Ram Singh (6/19 and 5/16) became the first to capture 10 or more wickets in the same Ranji Trophy game, and BR Nagaraja Rao, a quick bowler of some repute in Mysore cricket circles, bagging the first Ranji Trophy “pair.”

The chronicler is indebted to statistician C Keshavamurthy for many of the details of the historic encounter narrated above, and to statistician SK Gurunathan for recording the proceedings of the match in his book Twelve Years of Ranji Trophy. It may be mentioned that SK Gurunathan had later become the first Honorary Official Statistician of to the Board of Control for Cricket in India (BCCI). Gratitude is also due to Jayanth Kodkani of the TNN agency, particularly for the inputs on the five Englishmen who had represented Mysore in the match.

The story of the first ever Ranji Trophy match would not be complete without its denouement at Bangalore railway station on the morning of 5 Nov/1934. Contemporary media reports had spoken of a relatively chilly and overcast Bangalore morning with an eager group of local cricket enthusiasts gathered on the platform awaiting the arrival of the train in excited anticipation of the English newspapers bearing news of the pioneering Ranji Trophy match that had begun the day before at Madras. Those were the days preceding the advent of live running commentary over the radio.

As the train had pulled in, bunches of newspapers had been thrown onto the platform for later distribution. Even as the eager throng were in the process of gathering around the newspapers hoping to catch a glimpse of the headlines, they were stupefied to see dejected members of Mysore cricket team alighting on the platform from the train, looking shame-faced, and avoiding eye contact with the gathering. It was only then that the sad realisation of the inaugural Ranji Trophy match being concluded in only one day with disastrous results for the Mysore team dawned on the disappointed fans.

Conrad Powell Johnstone (on left), going out to open the innings for Madras in a Ranji Trophy match with V.N. Madhava Rao. The solar topee and fiddling with his left leg-guard as he went out to bat were characteristic of him.

The man and his milestones

Between the seasons of 1926/27 and 1944/45, Con Johnstone played 20 matches for Madras, scoring 1134 runs at 30.64, with a highest score of 94 and 9 fifties. He held 28 catches for his adopted home team. He also captured 24 wickets for them at 27.04, with best figures of 6/28 against Bengal in the Ranji Trophy Semi-Final at Chepauk in Feb/1936. Johnstone also shone with the bat in that Semi-Final, with scores of 93 and 36, allowing Madras to win the game by 91 runs.

A man of many endearing foibles, Johnstone was known to be extremely nervous when in the 90s, and he never reached a century for Madras. This agitation while in the nineties was not restricted to his personal batting. There are reports of his becoming increasingly apprehensive when any team-mate was to be seen nearing any landmark, be it a 50 or a century, in any match. It is said that he always carried a large towel in his bag, and would be found rummaging frantically for it as any team-mate approached the landmark. He would then wrap the towel around his waist, over his trousers, in the local mundu style, and wait at the top of the pavilion steps until the landmark was reached. He would then welcome the batsman back after dismissal, or at an interval of play, still with his towel around his waist like a fetish of some sort.

As good a player as he was, he was known to have been a very nervous starter at the beginning of any innings. NS Ramaswamy reports: “For a fine innings from him, everything about him, not excluding the sightscreen, should be perfect, but do not great artists need a fine canvas to paint their best picture? On such a day, Johnstone would take arms against the most formidable bowling combination and score a fifty or a hundred in a nonchalant manner. But the slightest hitch anywhere affects his batting to such a degree that he would leave his wicket to a ball which he would normally send for a six or four. His batting is characterised by the spirit of adventure and he revels when his team has to score over 200 runs in about 90 minutes.”

A remarkable feature of his cricket was his slip fielding almost throughout his career. In a match against the visiting Australian Services team touring India and Ceylon in 1945/46, at the conclusion of World War II, Con Johnstone was captain of a South Zone team against the visitors at Chepauk in early Dec/1945. He was 50 years old at the time. Opening the batting for his team, Johnstone was bowled by Keith Miller, visiting skipper for the game, for 18 in the 1st innings.

During the visitors’ 2nd innings, Johnstone held slip catches for three consecutive dismissals, the victims being Jack Pettiford, skipper Miller, and Ross Stanford. Miller himself had been the first to acknowledge that it was “the best catch that ever dismissed me.” In the words of Lindsay Hassett, the official captain of the touring team, but not playing in that particular game, “his (Johnstone’s) slip fielding is astonishing. The catches with which he dismissed Pettiford and Miller would have done credit to a JM Gregory or a Wally Hammond.”

According to the veteran cricket journalist KS Narasimhan, “His (Johnstone’s) greatest contribution was cementing European-Indian relations, which threatened to break up due to the snobbishness of a few overzealous MCC (Madras Cricket Club) members, more so after the control of the game was taken away from the Club and went to the new democratic Madras Cricket Association.”

Part of the folk-lore of Madras cricket revolves around the oft-repeated scene of Johnstone in earnest conversation with legendary groundsman Munuswamy after the draw of stumps at Chepauk on any given day, working out the finer details of the exact actions to be taken to give every blade of grass the best possible care on their mutually beloved cricket ground. It was in the fitness of things that the MCC Pavilion at Chepauk was renamed the CP Johnstone Pavilion in 1997.

Con Johnstone had been one of the principals involved in the setting up of the Board of Control for Cricket in India when the regulatory body had come into being in 1928. In the succeeding years, Johnstone held several influential and responsible posts in public life and in cricket, becoming the President of the Madras Cricket Club in 1947, the Chairman of the Madras Chamber of Commerce, chairing the Madras Club, and the Indian Roads and Transport Development Association with great distinction.

He finally returned to England in 1948 and was elected to the Kent County Cricket Committee, becoming the President in 1966. Never losing his interest in Indian cricket, he stayed in contact through the Indian tours to England. There is a famous story related by TM Srinivasan in connection with the historic England-India Test match played at The Oval in late Aug/1971, a match that India had won by 4 wickets, thanks to a brilliant exhibition of bowling by BS Chandrasekhar (6/38) in the England 2nd innings.

One of the abiding images of the Test had been the brilliant and blinding catch taken at gully by Srinivas Venkataraghavan off the bowling of Chandrasekhar to dismiss Brian Luckhurst for 33 in the England 2nd innings, leaving the home team at 7/72. It may be recalled that England’s 2nd innings tally had amounted to 101 all out, leaving India a victory target of 173 runs.

It is said that when the victorious Indian team, led by Ajit Wadekar, was returning to the pavilion, an elderly Englishman, tall and broad-shouldered, had met Venkataraghavan with a smile and a compliment as the Indian off-spinner had been about to enter the pavilion. “With a name like that,” the gentleman had remarked, “you must be form Madras!” The gentleman in question was Conrad Powell Johnstone.

It was on the rest day of the Lord’s Test of the 1974 series between England and India that the legendary Con Johnstone’s mortal innings ended on 23 June/1974 at Eastry, just over two miles away from Sandwich, Kent, where Johnstone had spent the evening of his life. In the words of his son Tony, “Bringing people together and making friends through a shared love of cricket was his fulfilment.”