Frank Chester, born January 20, 1895, was a promising cricketer when his career was derailed by the loss of an arm. However, he became the most respected of umpires. Pradip Dhole looks back at the life and career of this extraordinary character.

“Infallibility, it seems, and nothing else, is good enough. Even Len Hutton or Alec Bedser is permitted an occasional lapse from grace. But umpires, never. It prompts the paradoxical thought that the Perfect Umpire, assuming that such a one ever existed, has probably never been heard of by the world at large. He made the mistake, in Irish parlance, of never making a mistake. Of all the umpires of modern times no one has figured more largely, both in print and popular esteem, than Frank Chester. It is safe to assume, then, that he has made his mistakes. But, if so, they have been remarkably few, and have served to accentuate, not minimise, his virtues. If anything, he is the exception that proves the rule. His good points claim more attention than his bad ones.”

- Vivian Jenkins, in Thirty Years as an Umpire, his tribute to Frank Chester in the 1954 edition of Wisden

Arthur William, in his An Etymological Dictionary of Family and Christian Names, published in London in 1857, says that the family name of Chester is derived “From the city of Chester, the capital of Cheshire, England, founded by the Romans. The name is derived from the Latin Castrum; Saxon, ceaster, a fortified place, a city, a castle or camp, it being a Roman station where the twentieth legion was quartered. "

The budding cricketer

This is the story of a descendant of an ancient English family whose name had been annotated as Cestre in the Domesday Book of 1086. The earliest family member noted in the Pipe Rolls was one Richard de Cestre, in the notification for the year 1200. As seen above, history tells us that the family hails originally from Cheshire, later spreading to other parts of England. Over a period of time, the family adopted the more simplified name of Chester.

Founded on 1 May, 1864 as one of the oldest organised cricket clubs of Hertfordshire, Bushey Cricket Club will be celebrating 155 years of existence this year. The club had been founded on extensive grounds that had also boasted a medieval Manor, thought to have been built in 1231. The original timber pavilion at the Moatfield ground at Bushey had reportedly been burnt down by German incendiary bombs during the War. Subsequent to the damage caused by the conflagration, all 22 players from both teams had to become accustomed, perforce, to sharing a small pre-cast concrete garage as a changing room, devoid of the luxuries of electricity, heating, an independent water source, or even a toilet. All that has changed now, of course, and life is much more comfortable for the modern-day cricketers of the venerable club.

A young boy from a local Bushey family, born on 20 Jan, 1895 (there is some ambiguity on this issue as his birth year has also been reported by some authorities as being 1896), was to play a prominent role in some of the legends that surround the ancient cricket establishment. Frank Chester, born in Bushey, and already a prodigiously gifted left-handed all-rounder, joined the club as a mere 12-year old in 1907, the season in which the “googly quartet” from South Africa were wreaking havoc with the cream of English batting. In the following year, aged 13, he topped the club batting averages. In 1909, when Chester was about 14 years old, it was Alec Hearne of Kent and England, who had recommended that he try to qualify for Worcestershire. Chester played for the 2nd XI in 1910 and 1911, enhancing his skills all the time.

The following is an excerpt from a 1951 speech by Mr. Robin Nicholls, President of the Bushey Cricket Club, then in his first year of Presidency of the Club: “Quite the best-known personality who was a member of the Club was Frank Chester, a world-renowned Umpire. Frank started his cricketing career at the age of 12 with the club. Sometime during that year, he scored a century against a very strong M.C.C. side. So impressed were they that they had a collection for him and presented him with £8, a considerable sum in those days equivalent today to something over £250 by today’s standards. By the age of 16 he had signed up for Worcestershire and one year later he had scored three centuries. Wisden at that time confidently predicted that the young Chester would play for England in the near future.”

Unfortunately, the scorecards from this early phase of the cricketing career of Frank Chester have, very regretfully, not been passed down to us, a great loss to cricket historians and aficionados. However, all his contemporary players and coeval media reports are unanimous on the issue that Frank Chester had been a very promising left-hand batsman and a slow left-arm orthodox bowler of great promise, and known to also produce the occasional chinaman to confuse opposing batsmen.

The first available documentation of Chester’s cricket career is a scorecard from a 2-day second-class game between a Worcestershire 2nd XI and a Warwickshire 2nd XI played at New Road Worcester, from 1 Aug/1910. In his 16th year at the time, Chester is seen to have scored 3 and 2, and to have picked up 1 wicket in the Warwickshire only innings. The dominant feature in the Warwickshire victory by an innings and 119 runs was a stand-out performance of 200 by Jack Parsons, later to play 355 matches for Warwickshire.

Chester as a young cricketer

Popular myth has Frank Chester making his first-class debut with Worcestershire as a professional cricketer at the tender age of 16 years and about 6 months. If we consider the standard archives, however, we find that he had, in fact, already celebrated his 17th birthday (assuming that he had been born in January, 1895) when he first turned out for Worcestershire against the visiting South Africans at New Road, Worcester, from 23 May, 1912, the year of the Triangular Tournament. Batting at # 11 in both innings, he was the last man dismissed in a 1st innings total of 50 all out in the 40th over, being stumped off Pegler for a duck. He remained undefeated on 10 in a 2nd innings total of 206 all out. His performance with the ball amounted to 12-0-53-0. Riding a century by opening batsman Gerald Hartigan (103), the South Africans won the match rather easily by an innings and 42 runs.

Chester played 15 matches in his debut year, scoring 146 runs with a highest of 27*, and an average of 9.73. His bowling feats were more rewarding in the same season as he captured 21 wickets at 26.71, with best figures of 4/52 against Kent at Catford in July. His performances, both with bat and ball, were to improve substantially in the following season.

Against Somerset at New Road from 26 June, 1913, facing a 1st innings total of 383 all out, powered by a double century (257* in 235 minutes) by Len Braund, and coming to the crease at the fall of the 6th wicket at the total of 107, young Chester, barely in his 18th year, held the innings together with a collected 115 (in less than 3 hours), his maiden first-class century. Worcestershire reached a respectable 344 all out and won the match by 8 wickets.

It is said that Chester’s performances in 1913 had impressed one and all, including Dr WG Grace, the Champion, and that Chester had been summoned to meet the great man, who had been fulsome in his congratulations, particularly on Chester’s century (148*) against Middlesex at Lord’s in end-August. Wisden described him as the “youngest professional regularly engaged in first-class cricket ... Very few players in the history of cricket have shown such form at the age of seventeen and a half. Playing with a beautifully straight bat, he depended to a large extent on his watchfulness in defence. Increased hitting power will naturally come with time. He bowls with a high, easy action and, commanding an accurate length, can get plenty of spin on the ball. Having begun so well, Chester should continue to improve and it seems only reasonable to expect that when he has filled out and gained more strength, he will be an England cricketer.”

Phil Tufnell, in his book Tuffer’s Cricket Hall of Fame, remarks: “he (Chester) became the youngest English batsman to score a century in the County Championship…” Simon Wilde echoes a similar opinion in England: The Biography: The Story of English Cricket: “No one had scored a championship hundred at a younger age, and he added three more centuries before turning 20…” The County President, Lord Cobham, had this rather startling statement to make: “Probably no cricketer of 18 had shown such promise since the days of WG Grace.”

In an article appearing in The Telegraph in 2014 on promising cricketers whose careers were cut short by World War I, Scyld Berry writes: “….was Frank Chester, of Worcestershire – so promising indeed that he could be called the most talented teenaged professional that county cricket had seen to that point, bearing in mind that W G Grace was an amateur in name, if not spirit. By the time the war broke out, Chester had scored four first-class centuries – a couple of them brilliant, notably a match-winning one against Middlesex at Lord’s – and taken 81 wickets with his off-breaks, and he was not yet 20.”

The tragedy

An event occurring in Sarajevo on 28 June, 1914 was about the change the dynamics of the political scenario in Europe with disastrous results. A Yugoslav nationalist, the Bosnian Serb Gavrilo Princip assassinated the heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, precipitating the July Crisis in Europe. The situation deteriorated by the day culminating in the polarisation of the major European powers into two coalitions: a Triple Entente, comprising France, Russia, and Britain, and the Triple Alliance of Germany, Austro-Hungary, and Italy. By 2 August/1914, war had been declared in the European theatre. The smouldering disquiet was out in the open now and a Pandora’s box of misery was about to be unleashed on the global populace.

It was with the backdrop of the above sombre situation on the Continent that the match between Worcestershire, playing on their home ground, New Road, and Derbyshire, began from 29 Aug, 1914. This time, the home team was being led by someone other than a Foster, and William Taylor won the toss for Worcestershire, opting for first strike. The 3rd home wicket fell at 73, and Chester, at # 4, was joined in the middle by Maurice Foster of the famous Worcestershire brotherhood. The 4th wicket realised 121 runs, the backbone of the innings, and was terminated by the dismissal of Chester (run out for 43). Maurice Foster played the defining hand of the innings, compiling 158 runs in under 2 hours, with 27 fours, and 1 six. The total reached 311 all out in 68 overs, the runs coming at the rate of 4.57 runs per over.

Derbyshire were dismissed for a 1st innings total of 206, conceding a lead of 105 runs to the home team. Two Foster brothers, Geoffrey (32), and Maurice again (52, the only fifty of the innings) helped to push the total up to 130 all out, setting Derbyshire a winning total of 236 runs. The visitors reached the target easily enough, winning the match by 5 wickets. All-rounder Sam Cadman (119*) was there at the end to savour the victory. Frank Chester would have been unaware of it at the time, but this was to be the last first-class match of his brief career.

In his 55 matches between 1912 and 1914, Chester scored 1773 runs at 23.95, with a highest of 178* against Essex earlier in Aug/1914, reaching his 1000 runs for the season, and the landmark of 1500 first-class runs with this knock, and hitting JWHT Douglas for four sixes in one over. He had 4 centuries and 4 fifties, and held 25 catches. He also had 81 wickets with his mixed bag of left-arm offerings. His best figures were 6/43 against Hampshire at Southampton in Jul/1913, Chester also scoring 128* in the 1st innings of the same match. At the end of his career, Chester had a strike rate of 63.49, and an economy rate of 2.98.

With the European situation becoming graver with each passing hour, the venerable Dr WG Grace wrote a letter to the English cricket establishment that was published in The Sportsman of 27 Aug, 1914. Part of it read as follows: “I think the time has arrived when the county cricket season should be closed, for it is not fitting at a time like this that able-bodied men should be playing cricket by day and pleasure-seekers look on. I should like to see all first-class cricketers of suitable age set a good example and come to the help of their country without delay in its hour of need."

The last pre-war County Championship match was played between Sussex and Yorkshire at Hove from 31 Aug/1914, the match ending on 2 September. Two other scheduled championship matches, Sussex v Surrey at Hove from 3 Sep/1914, and Surrey v Leicestershire at The Oval from 7 Sep/1914, were abandoned because of the onset of World War I. The war came closer to English households when Britain declared war on the Austro-Hungarian Empire on 13 Aug/1914. In the opinion of Martin Williamson: “In all, 210 first-class cricketers are believed to have joined up, of whom 34 were killed. However, the obituary sections of Wisden between 1915 and 1919 contained the names of hundreds of players and officials of all standards who had died.”

One young English first-class cricketer who answered the call of duty in 1914 was the 20-year old Frank Chester, rubbing shoulders, as it were, with thousands of the cream of the youth from both camps, as cricket suddenly became an issue of much lesser importance in the larger scheme of things. He volunteered for service in the Royal Field Artillery, joining war service at Lewes in a brigade under the command of Major Frederick Allsopp, the skipper of the Worcestershire 2nd XI, under whom Chester had played in 1911.

He saw action during the Second Battle of Loos from 25 Sep/1915, beginning with a continuous 96-hour artillery barrage on German positions. This was followed by the release of 150 tons of poison gas from 5,500 cylinders. Chester later moved on to Salonika, Greece, where a massive multinational Allied Force, numbering some 500,000 men, under the French General Maurice Sarrail, was preparing for an offensive. By March/1917, Chester was part of the British Salonika Force under General George Milne.

It was in July, 1917, that Chester, engaged in guarding an ammunition dump, suffered shrapnel injuries to his right upper limb during an attack by enemy aircraft. Under the primitive living conditions faced by the soldiers from both camps, and given the paucity of requisite medical equipment at hand in the war zone, Chester’s wound began to fester. About 3 days after he had incurred the injury, and following a series of failed operative attempts to save his limb, gangrene began to set in, and the right forearm had to be amputated below the elbow, putting a full-stop on any cricket that he may have planned for after the war. He was honourably discharge from the army in August/1918. Phil Tufnell quotes him as remarking in his later years: “Summertime, cricket being played again, and I, a professional with no right arm!”

The loss of his right forearm at the age of 22 and a half years was a crushing blow to the future hopes of the young man, but there was an element of resilience in the mind of the descendant of a proud family whose motto had always been Vincit qui patitur, which translates freely to “He conquers who endures.” Coming to terms with the sad reality that he was now never going wear the coveted England cricket cap that had been so widely predicted for him before the onset of the war, Frank Chester chose an alternative option to remain very much a part of the game he loved.

Chester had reportedly tried his hand at playing cricket one-handed for a while, pushing the ones and twos, and taking catches with his left hand. Being a practical man, however, he soon realised that it would no longer be possible to play cricket at the highest level with his handicap. It was former England captain Sir Pelham Warner who encouraged Chester to take up umpiring as a vocation, saying: “Take it up seriously, Chester. One day, you’ll make a fine umpire”, prophetic words from the experienced cricketer.

The Umpire

Back in England, Chester qualified as a first-class umpire, and made his debut in the match between Essex and Somerset at Leyton from 13 May/1922. He was in his 28th year at the time. Commenting on Chester’s debut match as a first-class umpire, Vivian Jenkins writes: “… young Chester was called on to give decisions against both captains, Johnny Douglas and John Daniell, and did his duty according to his lights. Douglas LBW, Daniell stumped (off the first ball he faced). ‘You’ll be signing your death warrant if you go on like that’, he was warned by his venerable colleague (Harry Butt), but Chester has gone on giving out captains ever since, reports to Lord’s notwithstanding. Chester’s integrity is perhaps more notable when it is remembered that Johnny Douglas won the Middleweight Boxing Gold Medal at the 1908 London Olympics and 6-foot-7-inch, 16-and-a-half stone John Daniell played rugby union for England.”

There is a small anecdote of human interest attached to this debut match of Chester as a first-class umpire. It seems that before he had reported for umpiring duty in the match, he had picked up six small pebbles from his mother’s garden at Bushey to use for counting the balls delivered in the over. Legend has it that he was to use the same six pebbles for the same purpose for the entire duration of his umpiring career.

Chester’s obituary, published in the 1957 edition of Wisden, contains the following observation: “…. at the end of the 1955 season he retired, terminating a career in which he officiated in over 1,000 first-class fixtures, including 48 Test matches (the bold letters have been inserted by the chronicler).” In fact, there are other sources that claim that he had been the first man to officiate in 1,000 or more first-class matches. While it is very possible that many of the scorecards of his earlier matches as umpire may have been damaged, destroyed or otherwise lost to posterity, The Association of Cricket Statisticians and Historians places him at the head of the list of the highest number of first-class matches as umpire with the figure of 774 matches against his name, followed by Tom Spencer of Kent, with the figure of 701. Chester’s total includes 531 County Championship games and 48 Test matches (the most in his time). He is also known to have officiated in 18 “Miscellaneous” games and 2 Army matches.

Over a period of time, Frank Cheater became a highly respected and iconic figure on the cricket field, tallish but spare of build, and with a slight forward stoop. Scyld Berry was to remark in 2014 that: “He was the first to crouch low over the stumps, a fashion which has gone out of favour but for which there is much to be said: if you don’t have television cameras and the Decision Review System, it has to be a better position from which to judge the height of an lbw appeal than standing tall.” Chester’s preference for a dark trilby hat in addition to the long white coat while officiating usually identified him on the field. Having lost a large part of his right arm, his artificial right limb, encased in a dark leather glove, became another of Chester’s identifying features.

In their compilation called All in a Day’s Cricket: An Anthology of Outstanding Cricket Writing, the editors, Brian Levison and Christopher Martin-Jenkins, include an extract from the autobiography of an Essex opening batsman named Thomas Carter “Dickie” Dodds. The extract reads, in part: “Frank stood in my first county game. I sensed his appraising eye on me, as it was on all new players. He was rather like a connoisseur of wine, savouring a new vintage. ‘Who’s this feller?’ he would ask an old player. I am told he would always try and give encouragement to a beginner. At any rate, I seemed to pass his inspecting eye in that first match, and he said some kind words.”

Chester made his Test debut two years after he began his first-class career as an official. The occasion was the 2nd Test against the visiting South Africans, and the venue was Lord’s, the headquarters of cricket, the date being 28 June/1924. In his debut Test, Chester was partnered by former England Test cricketer, HI “Sailor” Young. The match notes indicate that the scorers for the Test had been one Caldicott, and one Rippon. At the age of about 29 years and 6 months, Chester was the youngest ever Englishman to umpire a Test match, his outward appearance often belying his skill, judgement and acumen.

This was to be the first step in a 31-year journey that was to end at Headingley on 26 July, 1955, the opposing teams again being England and South Africa. Keeping in mind the fact that the number of Test matches played during this period of cricket history was much less than at present, it is quite amazing that Chester’s Test career as an official was to encompass 48 Test matches, a record number for the times. The record was first overtaken by the English umpire Harold “Dickie” Bird, who ended his career in 1996 after having officiated in 66 Tests.

A few incidents

In an article appearing in the Watford Observer in late Oct, 2014, David Crozier cites an interesting observation made by one Mr Barry Darsley of Buckinghamshire: “Frank travelled around the cricket grounds on a specially adapted motorbike.” When contacted, Frank Chester’s granddaughter, Jane Read, though immensely intrigued by the information, denied any knowledge of this mode of Chester’s transport.

Here is an incident reported in a brochure of the Essex County Cricket Club about an interesting situation arising in a championship match between Essex and Somerset in June, 1926, the first championship game ever played at Chelmsford, at a time when Chester was still a relative newcomer to umpiring. John Daniell won the toss for Somerset and opted for first strike, but the visitors laboured to a total of 208 all out in the 97th over. Middle-order batsman Jack MacBryan held the innings together with a score of 80. Essex replied with an even more laborious 178 all out from 102 overs, with “Farmer” White picking up 5/57 from his 44 overs. The Somerset 2nd innings total amounted to 107 all out, leaving the home team a winning target of 138 runs.

The 5th Essex wicket fell at 60 before Stan Nicholls (23) and wicketkeeper John Freeman (37) put on 54 valuable runs for the 6th wicket in 45 minutes. The 6th and 7th wickets then both fell at the total of 114. Essex now needed 24 runs to win the game with 3 more wickets in hand. The 8th wicket fell at 133, with 5 more runs still needed for a win. Skipper Percy Perrin (15*) and Laurie Eastman (0), levelled the score with one minute of play left till scheduled stumps. At this point, Eastman was bowled by Jim Bridges (5/33). Last man Gerald Ridley ran out onto the pitch to score the winning run.

Before Ridley could reach his batting position, however, Frank Chester looked at the clock and calmly removed the bails, leaving the scores level. At the conclusion of the match, it was the opinion of the umpires, Chester and Jimmy Stone, that, as per the laws in force at the time, Somerset would be deemed winners on a 1st innings lead. The 50-year old Percy Perrin, standing in for Essex skipper JWHT Douglas in this game, and on the point of returning to the pavilion, was not amused, and the matter was referred to the MCC for a ruling. After much thought and discussion, the MCC authorities were of the considered opinion that the match should be deemed to have ended in a tie and that the 5 points were to be shared between the two teams. Consequently, this match produced the first ever tie in the history of the Essex County Cricket club, the new venue making its championship debut in spectacular fashion.

Here is an extract from the match report appearing in The Times of 19 June, 1926: “At Chelmsford yesterday, there was an intensely exciting finish to the match. The home side with a full innings to play had been set 138 runs to win. They had scored 137 of these when Eastman, attempting to run a single was caught. Half a minute then remained for play but as Ridley, the last man, ran to the crease, the bails were removed by the umpires and Mr. Perrin, the Essex captain walked in. Thus, the match was drawn with Somerset securing points for a lead on first innings. Before the players left the field, John Daniell, the Somerset captain was apparently calling Mr. Perrin back but the game was not continued. Instructions issued by the MCC state: ‘If a wicket falls within two minutes of “time”, the umpires should call “time” unless the incoming batsman claims his right to bat for the time remaining.’”

Throughout history, cricket has always been an evolving entity, a “work in progress”, as it were, and the laws of the game have been part of the evolutionary process. A cricket blog written by a very well-informed aficionado of the game going by the enigmatic name of An Occasional Cricket Statistician brings to light an interesting fact regarding changes in the laws of the game. In April/1929, the Advisory County Cricket Council (ACCC) mooted three experimental changes in the extant laws of the game:

· That the size of the wicket be increased by an inch, both in height, and in width.

· That the use of the heavy roller be restricted to 7 minutes instead of the customary 10 minutes.

· That a new law, tentatively called the Snick LBW law, be introduced.

The citation of the Snick Law was strange, to say the least, the import being that a batsman would be declared out LBW if struck by the ball on the pads in line with the stumps, if, in the opinion of the umpire, the ball would have gone on to hit the stumps, even if he had deflected it by bat or hand first. The ACCC then sent a questionnaire to players and umpires at the end of the 1929 season asking for their feedback and opinion regarding the sustainability of the 3 new alterations to the existing laws.

There was uniform agreement with the first two issues, the bowlers being most vociferous in their endorsement of the new statutes. There was some division of opinion about the “Snick LBW” law. The response from the bowling fraternity was surprisingly lukewarm in this regard. Discussion on the issue raised one important point: as per the wording of the new Law, a batsman would have to be declared out LBW even if he were to play the ball down from the full face of the bat, and the ball were to subsequently roll on to hit the pad or foot, and would then have gone on to hit the stumps. This was the contentious issue for most cricket experts of the day.

In his comments in The Umpire’s Point of View in the 1933 edition of Wisden, Frank Chester stuck his head out with the opinion: “the experimental rule regarding LBW and ‘the snick’ has been a very good one, and I think it has come to stay (the bold letters have been inserted by the chronicler)”. For once, Chester’s opinion proved not to be as definitive as his on-field decisions, and the business of the “Snick LBW” died a natural death soon after the publication of the 1933 edition of Wisden.

Frank Chester’s first experience of the pragmatic flavour of Australian cricket in the capacity of an umpire (he had played for Worcestershire against Syd Gregory’s 1912 Australians) was in the second first-class match of the Australian tour of England in 1926 under Herbie “Horseshoe” Collins, in the game between Essex and the visitors at Leyton in the first week of May. After the first day’s play was totally washed out, the Australians scored 532/8 against a hapless Essex attack on the second day, even though skipper Collins was dismissed for a duck before the scoreboard had begun to move. A rollicking 2nd wicket stand of 270 runs between the scholarly schoolmaster Bill Woodfull (201) and the one-drop man Charles Macartney (148) set the tone of the rout of the home bowlers. The truncated game was drawn when the third day was also affected by the weather.

The weather seemed to be following Chester when his first Test involving the Australians, the 1st Test at Trent Bridge was all but rained off, there being no play on the 2nd and 3rd days of the scheduled 3-day Test, and very little cricket being played on the first day. The other Test that Chester officiated in happened to be the 5th Test at the Oval which England won by 289 runs. For England, the elite performers were the openers, Jack Hobbs (37 and 100), and Herbert Sutcliffe (76 and 161). A young quick bowler, Harold Larwood of Nottinghamshire, made his second appearance for England in this match. The match turned out to be a bit of a watershed for both countries with several players playing their final Test matches. The list included the veteran English wicketkeeper Herbert Strudwick, and the Australians Warren Bardsley, Charles “the Governor-General” Macartney, Tommy Andrews, skipper Herbie Collins, Arthur Richardson, and the enigmatic leg-spin and googly bowler Arthur Mailey.

Marks of Genius

With time, an aura began to grow around the quality of Chester’s umpiring. Once, when asked whether there had ever been any doubt whatsoever in his mind about any one of his numerous decisions on the field, Frank Chester is reported to have responded with: “Doubt? When I'm umpiring, there's never any doubt." Jim Swanton, the highly acclaimed cricket correspondent, once described Chester as being “as nearly infallible as a man could be in his profession.”

In an article about umpire “Dickie” Bird in the 1997 edition of Wisden, former England and Glamorgan captain Tony Lewis made the following observations about the past umpiring great, Frank Chester: “In Frank Chester's day, umpires were seen but rarely heard. They had been brought up as players on ground staffs in counties captained by amateurs but heavily influenced by the senior professional. There was hierarchy and discipline, and so the control they exerted as umpires was by the odd word to the captain or senior pro - and perhaps only a whisper: ‘Have a word with your fast bowler. He's pushing his luck with that appealing’. Chester virtually created the modern profession of umpiring by his serious approach to the smallest detail.”

There is a story from the 1930s, apocryphal perhaps, of a Surrey batsman hitting the ball with tremendous force straight at Chester crouching low over the bails in his characteristic posture. The force of the blow did not allow Chester to evade the ball entirely, and it hit the artificial right limb, knocking it off completely from its moorings, and sent it flying to strike the sight-screen. Chester was forced to dash after it, and having retrieved the errant limb, to leave the field to have it reinstated. It is reported that a county member had offered Chester a brandy in the pavilion, an offering that he had gladly accepted and savoured before returning to the field.

Chester was fond of remarking that the stump of his artificial right arm often acted as a barometer on the field, and when it ached, he could be sure of the prospect of rain in the air. The story got around after a while and there would be polite enquiries from anxious players when there would be rain in the offing: “Is the arm aching today, Frank?”

The Australians were the visitors in the summer of 1930, and Chester met them for the first time at Southampton on the last day of May in the match against Hampshire. There had been much talk in the press about the two young guns that the Australians were about to unleash on England on the tour, both right-handed upper order batsmen. Archie Jackson of NSW was still in his 20th year, and Don Bradman, also of NSW, and about whom the experienced Surrey skipper Percy Fender had expressed serious reservations about his succeeding as a batsman in England, was just a year older.

Well, the scheduled 3-day game ended of the 2nd day with the visitors winning by an innings and 8 runs. Bradman quickly dispelled any doubts about his adaptability to English conditions by scoring 191 at the top of the order, though Jackson, not enjoying the best of health in the damp weather of England, was dismissed for a duck in his only innings (even so, Jackson was to go past the 1000-run mark during the course of the tour). The game changer, however, proved to be the wily leg-spin and googly bowler Clarrie Grimmett, in his 39th year, with figures of 7/39 and 7/56.

In all, Chester was to officiate in 6 matches involving the Australians in the summer, 2 of these being Test matches. Blessed by fine weather throughout, the 2nd Test at Lord’s turned out to be a high-scoring affair with Duleepsinhji (173) achieving his highest Test score in the England 1st innings of 425 all out, with 405 of the runs coming on the first day of the 4-day Test. Not to be outdone, Australia replied with a 1st wicket stand of 162 between skipper Bill Woodfull (155) and Bill Ponsford (81). This was followed by Bradman’s famous 254, by his own estimation, his best ever batting performance. Alan Kippax contributed 83 in an Australian 1st innings total of 729/6 declared. Although English skipper, the stylish left-handed Percy Chapman scored a beautiful century (121) in the 2nd innings, it was not enough to prevent Australia from winning the Test by 7 wickets.

Following an age-old tradition, there was rain at Old Trafford during the 4th Test, and the match ended in a draw. By the end of the tour, Chester had seen enough of the new-look Australians, and had begun to form a mutual feeling of admiration and respect with regard to Bradman. In his famous book The Art of Cricket, Sir Donald Bradman begins his chapter on Umpires with the following words: “For those wonderful chaps who perform this thankless task, I have the most profound admiration. Not for them any financial reward. Not for them the honour and glory, but what a storm breaks around their heads if they give wrong decisions.”

In Chester’s opinion, the three basic assets for a successful career as a cricket umpire are these: keen hearing, good eyesight, and a very thorough knowledge of the Laws of the game. Above all, the umpire is obliged to bear the dictum of impartiality like a banner at all times. In Chester’s own words, “You never umpire for this team or that. You just umpire.”

In Farewell to Cricket, first published in 1950, Sir Don goes on record with the statement: “Without hesitation, I rank Frank Chester as the greatest umpire under whom I played.” He elaborates as follows: “In my four seasons’ cricket in England, he stood for a large percentage of the matches and seldom made a mistake. On the other hand, he gave some really wonderful and intricate decisions. Not only was his judgement sound, but Chester exercised a measure of control over the game which I think was desirable.”

In later years, Richie Benaud, the modern-day sage of cricket, was to echo Bradman’s opinion on Frank Chester’s umpiring skills.

The Mercury (Hobart) of 30 July, 1938 carried a feature under the heading Bradman Qualifies As An Umpire, as part of the Bradman Life Story. In the article, Bradman, speaking in the first person, makes a special mention of an incident from a match played between an England XI and the 1934 Australians at Folkestone in the first week of September, remarking that it had been one of the finest umpiring decisions he had ever seen by Chester.

“Bill O’Reilly was bowling to BH Valentine, the Kent player. Valentine played at a ball pitched on the off stump. There was a distinct click, and as Bertie Oldfield took the ball behind the wicket, he, and all our fieldsmen near the stumps, including myself, shouted ‘How’s that?’ To our astonishment, Chester, calm and deliberate, stood motionless for a second or two, peering down the wicket. Then, slowly raising a finger, he said, ‘Out…..lbw.’ Valentine said afterwards that the ball had just flicked his pads, not his bat, and that he was perfectly satisfied that he was in front.” Sir Donald concludes the story with: “Even the usually infallible ‘Wisden’ was deceived. To this day, it is recorded in the scores of the match – ‘Valentine c Oldfield b O’Reilly.’” The scorecard of the match in CricketArchive validates Sir Don’s observation.

There is another umpiring decision by Chester that has earned the plaudits of Sir Don, and the great man has made special mention of it in his Farewell to Cricket. The incident related to the 1st Test at Trent Bridge on the 1938 tour. The records show Bradman as having been dismissed in his side's 1st innings, for 51, c Ames b Sinfield. “The ball turned from the off, very faintly touched the inside edge of the bat, then hit my pad, went over the stumps and was caught by Ames whilst all this was happening amidst a jumble of feet, pads and bat. I slightly over-balanced, and Ames whipped off the bails for a possible stumping. There was an instant appeal to the square-leg umpire who gave me not out, whereupon Ames appealed to Chester at the bowler's end, and very calmly, as though it was obvious to all, Chester simply said 'Out, caught,' and turned his back on the scene. It was one of those remarkable pieces of judgment upon which I base my opinion that Chester was the greatest of all umpires."

There is an interesting snippet about Frank Chester to be found in a brochure of the 458 Squadron, Royal Australian Air Force under the heading Cricket on Gibraltar during World War II, as follows: “On the lighter side, a few cricket matches occupied some recreation time on Gibraltar. The Army, Navy, South African Air Force and civilians already had teams and the Army more than one. A notable Test cricket umpire Frank Chester happened to be there in the British Mechanical and Engineers Army, who has been highly regarded in Don Bradman's Farewell to Cricket and the umpire Dickie Bird autobiography, umpired all matches.”

Attitude and Aussies

By 1948, Chester was unsympathetic with what he deemed “excessive and belligerent” appealing from the Australians in the field, and even when standing at square-leg, often made his displeasure felt by hand gestures to the bowler’s end umpire when he felt that the Australians were over-stepping the bounds of civility. He began to respond with a pronounced pseudo-Australian drawl of “Naht out!” The Australians were not happy with these traits of Chester. Simon Wilde quotes Chester as saying: “I thought (they) went too far with their appealing, which they often accompanied by excited leaping and gesticulating… Apart from being distasteful to the home players, as well as to the cricket-loving public, this sort of behaviour made umpiring a somewhat nerve-wracking business…. An exaggerated chorus of appeals can spoil the game, as well as bring upon an umpire the hostility of the crowd.”

Somehow, the chemistry between Chester and the Australians was never very good, despite the adulation of Sir Don. As reported by the Daily Mail of 15 March, 1950, Frank Chester chose to drop a bombshell at a gathering of the Derby Cricket Association on the evening of 14 March, as follows: “I never enjoyed one match in the Australian tour of 1948, and I don’t think any other umpire did. The Test match at Manchester was too bad for words. Even when our batsmen never attempted to play the ball, the Australians all shouted – even the captain from cover-point.”

Although England skipper Norman Yardley declined to make any comment on Chester’s tirade against the Australians, English umpire Claud Neville Woolley thought it fit to support Chester’s statement in the London press. The Australian Manager on the 1948 tour, Mr Keith Johnson, commented in Sydney that he was not aware of Chester’s views, and that he had not heard any questions raised about the Australians’ on-field or off-field deportment on the tour.

Australian cricket columnist Ray Robinson, who had covered the 1948 tour of England for the Australian press, introduced a new twist to the tale by bringing left-arm Australian fast bowler Ernie Toshack into the frame. It seems that Toshack was in the habit of shouting ‘Owizee!’ when appealing. Not familiar with the term, Chester had reportedly left his position once to consult skipper Bradman about this unfamiliar mode of appealing. It seems that Chester had then informed Bradman that if the bowler wanted his appeal to be officially recognised, he should use the standard form of “How’s that!” while appealing. Robinson’s final comment on the issue had been: “Surely Chester does not suggest bowlers should be robbed of their democratic right to ask whether they have got the batsman out?”

Obstructing the field and other issues

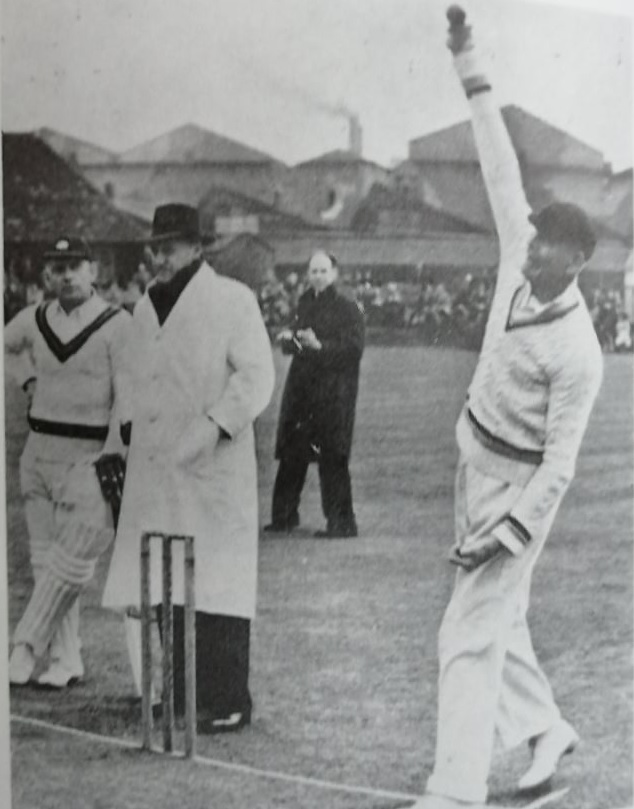

Frank Chester officiates at Stafford in 1953. It is the testimonial match of SF Barnes, 80, who is still active as a bowler. The batsman at the non-striker’s end is Cyril Washbrook

Around this time (1948), Chester began to feel the first footfalls of the demon that was to be the bane of his later years and would be instrumental in clouding over the incisive judgement that one had come to associate with umpire Frank Chester. The peptic ulcer problem began insidiously, perhaps as a result of the constant pressure that a first-class umpire is always subjected to during the course of his career. There being no definitive treatment of the condition in those days except rest and a modified diet, both impractical for a peripatetic cricket umpire during the summer season, the problem gradually became a constant source of discomfort and mental unrest for Chester. Events of the 1951 South African tour of England did not help the cause.

The 1951 season brought the South Africans to England on 20 Apr, 1951, and with them, some controversy. There were to be several health-related problems confronting the tourists on the tour, led by Dudley Nourse, and Hugh Tayfield had to be flown in to join the 15-man party as cover for Athol Rowan. Vice-captain Eric Rowan earned the ire of tour Manager Syd Pegler when he squatted on the pitch in retaliation to vociferous barracking from the crowd triggered by the slow batting of the South Africans. There was talk of sending Eric Rowan home about half-way through the tour, and on arriving back in South Africa at the end of the English tour, the errant vice-captain was informed through a letter that he would not be selected for the forthcoming Australia tour.

There was an unusual incident in the 5th Test match of the series at the Oval from 16 Aug/1951. The protagonist of the interesting slice of Test history was England opening batsman Len Hutton and the incident occurred in the England 2nd innings. Let us take up the story from Haresh Pandya in his tribute to South African wicketkeeper Russell Endean, making his debut in the Test mentioned above, and appearing in The Guardian in July/2003:

“Chasing a modest target of 163 runs, the home team were going steadily, with the two Yorkshire openers, Len Hutton and Frank Lowson, taking no undue risk. But with the score at 53, off-spinner Athol Rowan pitched a ball just outside the leg stump. Hutton, then on 27, snicked it on to his pad, from where it rose over his shoulder. He instinctively knocked the ball aside with his bat as it was falling. Endean, the wicketkeeper, was thus thwarted in catching the ball. An appeal was made, and after a pause the bowler's end umpire Dai Davies gave Hutton out, with the approval of the square-leg umpire, Frank Chester. It was some time before the spectators realised what had happened, and Chester had to go over to the scorers to inform them of the ‘obstructing the field’ dismissal, the only one of its kind in Tests.”

The South African touring party included a blonde 1.88-metre tall 22-year old right-arm fast bowler named Cuan Neil McCarthy. McCarthy had first exploded on the touring MCC team in their game against Natal on their 1948/49 South Africa tour. Wisden had noted at the time that: “On the opening day Nourse gave a severe test to 19-year-old McCarthy, whose pace was the main reason for the early uneasiness of MCC batting.” The youngster had acquitted himself well on that occasion, opening the bowling and capturing 5/110. McCarthy had made his debut when he was selected for the 1st Test at Kingsmead, Durban, from 16 Dec, 1948.

Commenting on his bowling, John Arlott had remarked at the time: “his involuntary variations of pace and direction denied the batsmen comfort, whilst his faster ball, slung in with a low arm, left them little time for deliberation about their stroke.” Martin Chandler feels that while these comments by Arlott had not been a definite indication of unfair bowling, the young tearaway seemed to have definite areas of concern regarding his bowling.

Chester’s first experience of McCarthy on his England tour of 1951 was in the game against the MCC at Lord’s, from 19 May/1951. The umpires for the game were Chester and Frank Lee, both ex-players, and experienced officials. Given McCarthy’s past reputation, both umpires had a long and hard look at his bowling action over the duration of the game, but made no call.

Let us now take up the story from the tour book, Noursemen in England, by South African columnist Cyril Medworth: “The test for McCarthy was safely passed and everyone breathed a sigh of relief. Frank Chester might not have been wholly satisfied, but he gave McCarthy the benefit of the doubt and other umpires did likewise thereafter….Every now and again, perhaps once in five overs, when he really lets one fly that falls a shade short, I fancy the elbow is not absolutely straight. It is more discernible when he is tired and is trying to keep a fiery pace…”

Martin Chandler’s assessment of the situation was: “Chester was less than happy with McCarthy. He told the South Africans then that he intended to call McCarthy and took some persuading not to. Quite what happened is unclear, and there are at least three versions. The first is that Eric Rowan, standing in as skipper for an injured Nourse, challenged Chester that if he did so he would stop the game and call Pelham Warner out on to the field and ask him to define a throw. A slightly less combative account is that Rowan proffered some friendly advice, pointing out that Chester himself as well as other umpires had not previously called McCarthy, and that perhaps he should think twice before risking a furore. The third version is that a discussion with Warner did take place and that ‘Plum’ the appeaser begged Chester not to rock the boat.”

In the book It’s Not Cricket, Simon Rae recalls some comment made by Norman Preston, editor of the 1952 edition of Wisden on the issue of Chester and the bowling action of McCarthy, as follows: “Frank Chester was standing at square leg and looking askance at McCarthy. Clearly unhappy at what he saw, he refrained from calling him, and after lunch, ‘rarely looked that way again.’ Some time later, I asked him the reason and he told me that he had gone without his lunch in order to find out whether he would receive official support if he no-balled McCarthy for throwing. He spoke to two leading members of the MCC Committee and could get no satisfaction. They were not prepared to say that MCC would uphold the umpires. In other words, Chester was given the impression that, if he adopted the attitude which he knew was right according to the Laws, there was no guarantee that he would remain on the panel of Test umpires. Naturally, Chester was not prepared to make a financial sacrifice in the interests of cricket, and McCarthy continued unchecked in Test matches.”

This sort of comment, coming from a person with acquaintances in high places and with an easy rapport with the hierarchy of English cricket, was very disheartening for Chester and did his ulcer no good. He gradually became a disgruntled and fractious individual, the attitude further complicating his medical condition. At this stage of his career, Frank Chester was clearly not at peace with himself.

The Association of Cricket Umpires was formed in England at the Kings Head Hotel at Mitcham, Surrey, in 1953. Elaborating on the issue, Tom E Smith, the Honorary General Secretary of the Association, wrote: “The Association has the blessing of the parent body, the M.C.C., The Club Cricket Conference, the National Association of Cricket Clubs, and other controlling bodies. From that start there are now over 200 names on the books. From all over the country the membership ranges through First Class County umpires, Minor County, M.C.C., C.C.C., the Leagues, the three Services and Club, to potential and trainee umpires.”

Tom E Smith emphasised the fact that the aim of the Association was “to improve the standard of umpiring.” It was decided that Members would be elected as Associates “on the understanding that they are willing to study and work to take the examination in theory and oral for ‘Full status’.” The Association made it clear that: “These examinations are difficult and the standard is high. Perfect answers to theoretical questions do not necessarily make a perfect umpire. His interpretation of the laws on the field must finally count.”

A brochure of the Association published in 1954 said: “The Training Committee consisting of senior umpires, all experienced in teaching and coaching, has prepared training schedules with a standard system of training and grading. The first examinations were held in London in January, and the examiners were Frank Chester and K. McCanlis, the county umpires. It is difficult to imagine anyone better qualified for the job.” Former England skipper Douglas Jardine became the first President of the Association, with Frank Chester, HM Garland Wells, K McCanlis, and John Arlott were named as vice-Presidents.

The return of the Aussies

The simmering undercurrent of intolerance between Chester and the Australians came to the fore during the 1953 Australian tour of England, in the Coronation Year of HM Queen Elizabeth II, then aged 25 years. The 17-member party was led by Lindsay Hassett, and contained two other 1948 tourists in Arthur Morris and Neil Harvey. Having disembarked from the Orcades at Southampton on 13 April/1953, the tourists played 33 first-class matches on the tour, including 5 Test matches, winning 16 of them, 11 of them by an innings. There were several disturbing issues concerning Chester’s equation with the Australians during the summer.

The 4th Test of the 1953 series, played at Headingley from 23 July, produced two of the worst ever decisions that Chester was to be guilty of in hi career. Bruce Maurice, writing in the Sunday Times Sports section on 21 Feb, 1999, cites an incident from the England 1st innings: “Reg Simpson hit Ray Lindwall past mid-on, and Hassett chased it in the direction of the Member's Stand. Miller who was at mid-off ran to the wicket to take the return. Hassett picked it up, and as he was about to turn and return, Miller turned around and saw Simpson just starting for his third run, Hassett sent in a perfect return, right over the bails. In the meantime, Lindwall was shouting, ‘You've got him Keith, you've got him.’ Miller collected the ball, removed the bails when he turned around Simpson was still coming home. The fielders thought the appeal was only a formality. But Chester seemed to have some trouble with his balance. Finally, he looked up and mumbled ‘Not Out.’ The Aussies were dumbfounded.

“They just could not believe it and made four more appeals. But all four appeals fell on deaf ears. They could not believe that Chester could allow Simpson to carry on batting and Miller in utter disgust dashed the ball on the ground.” It seems that even Chester had been unhappy with his own decision on this occasion, and had explained to Miller rather sheepishly that he had not been able to get into a proper position to make the decision. Chester’s explanation confounded the Australians completely because the batsmen had been running for the 3rd run at the time. Simpson was finally caught behind by Gil Langley off the bowling of Ray Lindwall for 15.

Chester’s second blunder followed in the England 2nd innings and involved Denis Compton: “Denis Compton had to retire with an injured hand when his score was on 61. On the following day Bailey and Laker held on for some time before Laker was out for 48. Compton returned and as soon as he came in, he snicked a ball from Ray Lindwall and was caught by Graeme Hole at 2nd slip. It was a clean straightforward catch. Of course, if Compton knew he was out, he would certainly have walked. Because cheating was one thing that was never in Compton's book. But he stayed because when he pushed forward, he did not know where the ball had gone.

“The Australians then appealed to Frank Lee. But Lee said he could not give a decision as Lindwall had obstructed his view when following through. So he consulted Chester at square leg. Chester no doubt could have seen it was a clean catch. But first he looked at Miller, then at Hole and said, ‘Not Out’. The blood rushed from Hole's face and he turned a deathly white.” It did not make much of a difference to Compton’s score, of course, because he was out to Lindwall, LBW for 61.

At the end of the Test, although Hassett had the grace to appear on the balcony and the Australians joined the England players in a post-match drink, according to Mark Peel in Playing The Game?: Cricket’s Tarnished Ideals From Bodyline to the Present, the Australians felt cheated. In Compton’s opinion: “It wasn’t cricket. The Aussies were furious. Their anger was justified.”

Lindsay Hassett took up the issue with the MCC, stating that Chester’s umpiring in the 4th Test had favoured both Simpson and Compton and that Chester had failed to intervene when Trevor Bailey had deliberately bowled down the leg-side with a packed on-side field when the Australians had been trying to chase down the winning target of 177 runs on the last day of the Test. Hassett made it clear that the Australians would not be happy with Chester being appointed for the last Test of the series at The Oval, after the first 4 Tests of the series had been drawn.

After lengthy deliberations, Chester was made to stand down from the deciding last Test, the official reason given to the press being his failing health. It is, of course, on record that England won the last Test by 8 wickets to take the series 1-0, and to finally bring home the Ashes after a gap of 19 years, having surrendered the coveted urn to the 1934 Australians 1-2, with 2 draws. Remarking on Chester being stood down, Wilde remarks: “It was a significant rebuke for English umpiring, which had to this point been regarded, at least in England, as the best in the world.”

South Africa’s 1955 tour of England was their 11th official Test tour and their 8th to England. It was made memorable by being the first on which the South Africans had flown out, the journey taking 26 hours to Heathrow, and with 7 stops en route. Historically, this was the first Test series ever played in England in which each Test had produced a definite result.

Final days

Chester’s Test umpiring career ended after he officiated in the 2nd and the 4th Test matches between England and the visiting South Africans of 1955, and he ended his career with 48 Test matches to his credit, a record number at the time, and a tribute to his abilities and his judgement. His last first-class match, his 774th, also followed later in the same season when he officiated in a match between an England XI and a Commonwealth XI at Hastings from 3 Sep, 1955, the England XI winning the game by 56 runs.

Frank Chester passed away at his home town of Bushey on 8 April/1957 respected by all his fellow-countrymen and was laid to rest in the grounds of St. James’ and St. Paul’s Church, Bushey, Hertfordshire. The “almost infallible” official had finally been declared out by the Celestial Umpire. Tributes poured in from prominent figures of the cricketing world, and Wisden published some of them, as follows:

· Mr. R. Aird, Secretary of M.C.C.: He was an inspiration to other umpires. He seemed to have a flair for the job and did the right thing by instinct. He was outstanding among umpires for a very long time.

· Sir John Hobbs: I played against him in his brief career and am sure he would have been a great England all-rounder. As an umpire, he was right on top. I class him with that great Australian, Bob Crockett.

· F. S. Lee, the Test match umpire: Frank was unquestionably the greatest umpire I have known. His decisions were fearless, whether the batsman to be given out was captain or not. There is a great deal for which umpires have to thank him.