Frank Worrell, born 1 August 1924, was a most delightful batsman to watch and became immortal as the first black man to lead West Indies in a full series. Arunabha Sengupta recalls the life and career of the man who formed a third of the Three Ws of West Indian cricket and left the world tragically at the young age of 42.

He never struck the ball, with gentle caresses he persuaded it to go where he willed. He never called the shots, yet a group of extraordinary talents followed the beam of his wisdom and became the best team in the world within five years. He lost a series in Australia as captain, but half a million fans lined the streets of Melbourne to bid his team farewell. He did not live beyond 42, but he remains immortal in the hearts of his cricket fans and the greater world beyond the game.

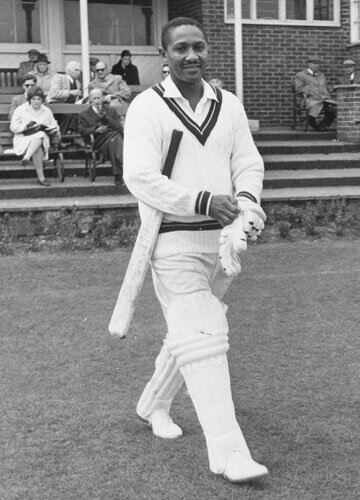

Frank Worrell at the crease was all grace, class and elegance. Off the field he was charming, dignified and tranquil. He was the first black man to lead West Indies in a full series and on tour, and the first-ever cricketer to be honoured with a memorial service at the Westminster Abbey.

Worrell was a legend in the newly-formed independent island of Barbados. His cricket was an expression of poetry, a gushing fountain of joy through the late 1940s and most of 1950s. And then he tarried, spending a couple years to complete his education, perfecting the mould of his personality in becoming the ideal ambassador of his people. And finally he continued his career to his cricketing middle-age, his numbers falling prey to the effects of time, but secure in the goal of proving to the world that a black man could indeed lead the country. He did more than that. He forged the team into an unprecedented West Indian whole without chinks and fissures between the coteries of Jamaica, Barbados, Guyana and Trinidad. He became the most successful captain of West Indies before Clive Lloyd and Viv Richards rode the four pronged pace machine to better his deeds. And forever he remained a statesman for Barbados, for West Indies and for cricket. The year after he played his final Test match, Frank Worrell was knighted for his services to the game.

Yet, for all the immense acts in the world of cricket and the associated bigger stage, it should never be concluded that cricket to him was a matter of grave seriousness. Few cricketers have ever viewed the game with an attitude as detached as Worrell. For him, it was always a game to be enjoyed. He seldom read sports columns, opinions and reports in the media. And no cricketer was blessed with his unique ability to nod off at every possible moment — opportune or not. When West Indies collapsed during that famous Lord’s Test of 1963, a Caribbean cricketer was waylaid by a journalist wanting to know whether Worrell was worried. He was informed that the captain was busy catching a few winks.

Under him the West Indian team remained a happy, fun-loving side, summarised in his own words as: “A bunch of comedians.”

The school cricketer

It is almost miraculous that an island 31 km in length and 23 km in width should produce three such magnificent cricketers born within 17 months and one mile of each other, delivered by the same mid-wife. Worrell, the oldest, was born in 1924 in Bank Hall, St Michael. Everton Weekes followed in February 1925, and Clyde Walcott in January 1926.

The ‘Three Ws’ of the West Indian cricket team attending a cocktail party at the West Indian Club, London, the day after their arrival in Britain, April 15, 1957. From left: Frank Worrell, Everton Weekes and Clyde Walcott. Sonny Ramadhin can also be seen behind, between Weekes and Walcott © Getty Images

Walcott was the only one to hail from a well-established middle-class family. Worrell was less fortunate by birth and Weekes lesser still.

Worrell was born to working-class parents who later moved to the United States and left him under the care of his grandmother. His father spent most of his days in the seas and the young lad seldom saw him. But, the resulting remittances that arrived in envelopes from the land of opportunities helped the young Worrell to get admitted to the Combermere School as a 12-year-old after attending Roebuck Street Boys’ for the first few years.

Frank Worrell’s batting photo appeared in a commemorative stamp issued by Barbados to mark the occasion of the 300th anniversary of the Combermere School.

One of the masters at Combermere was Derek Sealy, a former Test cricketer. It was under his tutelage that both Worrell and Walcott flowered after joining the school together in 1937. Walcott soon built a fearsome reputation as a hitter of the ball, while Worrell made it to the Combermere first XI as a left-arm spinner.

Worrell was never coached seriously, nor did he undergo arduous practice. But, he did model his technique on Sealy. And from the very beginning he adhered to one guiding principle — a mistake made in one innings would never be repeated in his career.

Yet, it was as a bowler that he made his first mark. He took seven for 18 against Harrison College at the tender age of 14. But there were qualified men to spot his batting talent. Another teacher at Combermere was Owen Alexander Pilgrim, an excellent medium-fast bowler for Barbados. Sealy and Pilgrim urged Worrell to focus more sharply on his batting. Although he was initially relegated to the tail-end, Worrell soon flourished with the bat as well. By the time he left Combermere as a 19-year-old, he was the foremost left-arm spinner in the island. But, alongside, he had also developed into a fantastic strokeplayer. He was still in school when he made it to the Barbados side and played for them in the Goodwill matches played during the Second World War.

It was the hand of fate which prompted him to become a leading batsman of the world. In 1943, in one of the Goodwill matches against Trinidad, Barbados lost a wicket towards the close of the day. Worrell was sent in as night watchman at No 4 and carried his bat to score 64. When Barbados played Trinidad again, he was sent in early and struck the ball with style and flair to score 188 and 68. The promotion in the order became permanent.

The following season Trinidad suffered even more. John Goddard hammered 218 and Worrell piled up 308 to share an unbroken partnership of 502, then a world record for the third wicket. And two years later, with Walcott for company, Worrell proved the scourge of the Trinidad attack again. Walcott slaughtered the bowlers for 314 and Worrell hit a delectable 255 as they put on 574 unbeaten runs for the fourth wicket, yet another world record. The very next year Vijay Hazare and Gul Mahomed went past it by adding 577 for Baroda against Holkar, but Worrell for long remained the only batsman to be involved in two separate 500 run partnerships. In 2012-13, this feat was also performed by Ravindra Jadeja.

In Barbados, Worrell played club cricket for Empire, always sparkling and regularly successful. On one occasion, he defeated the Police side singlehandedly, scoring 201 and taking 11 for 78. In 1947, he moved to Jamaica and continued his saga of success for his adopted island. However, the Bajans never quite forgave him for his supposed ‘betrayal’.

The Three Ws

By the time England arrived in the West Indies in early 1948 under an ageing Gubby Allen, Worrell was all set to make his debut. Walcott and Weekes made theirs in the first Test at Bridgetown, and Worrell had to wait for the second match at Trinidad. He batted at number four, between Weekes and Walcott in the order, and hit 97 with nine fours and a six before being caught at the wicket off Ken Cranston. But, he did not have to wait long for his hundred. In the following Test he amassed 131 and ended the series with 294 runs at 147.00.

Test cricket was a rare affair for the West Indians in the late 40s. Worrell filled up the time with astute accumulation of experience. A season was spent as a professional with Radcliffe, the Central Lancashire League club, ending with a record tally of 1,501 runs and 66 wickets. By now, he was using the English conditions thoroughly, having switched his style to incisive left arm fast-medium. In 1949-50, he toured India with the Commonwealth team, amassing 223 at Kanpur, scoring 684 runs at 97.71 in the unofficial ‘Tests’.

It was during the 1950 tour of England that the story of Worrell, Walcott and Weekes became the stuff of legends and the trio were christened ‘The Three Ws’. At Lord’s, Walcott slammed 168 not out as Sonny Ramadhin and Alf Valentine bowled West Indies to their first-ever victory in England. And at Nottingham, Worrell hit 261 and Weekes 129 as the spinners performed their magic once again. Yet another hundred followed at The Oval. By scoring 539 in the series, at 89.83, he brought his career average at the end of seven Tests to 104.12. Called upon to bowl rather less with his growing stature as one of the best batsmen of the world, Worrell used his fast-medium style to capture some vital wickets at Nottingham. And against Yorkshire, he bowled leg-theory — of a rather more benign variety than the English team of the early 1930s, and tilted the scales in the favour of West Indies in a tense, close struggle.

And as soon as the series ended, he was back in India again with the Commonwealth team, this time as vice-captain.

The highs and lows

The supreme streak with the bat did not last forever. On the hard wickets of Australia, facing the fastest of balls from Ray Lindwall and Keith Miller, Worrell managed just one hundred in Melbourne and a six wicket haul at Adelaide in an otherwise unimpressive tour. And the Tests that followed down the years seldom recaptured those phenomenal phases of run making of his first two series.

But, there were plenty of memorable innings. He caressed a magnificent 237 against India at Kingston 1953, one of the two occasions all the Three Ws scored hundreds in the same innings. The next year he hit 167 against England in Trinidad, and the three repeated the feat of scoring hundreds together. At the end of the series against England in 1954, Worrell’s numbers stood at 2,135 runs from 23 Tests at 61.00 with seven hundreds. Weekes was ahead in terms of average and both Worrell and Weekes in terms of runs. But Worrell was without doubt the most delightful to watch among the three.

Weekes was the most compact of the troika, possessing the best technique. He mastered the bowlers thoroughly with his solid attractive stroke-play. Walcott was the most thrilling to watch, a mighty hitter with unlimited aggression who demoralised the best of attacks. No one could drive more powerfully, both off the front and back-foot. But among the three Walcott was an artist, a joy to behold when in full flow. He never played across the line, which meant he never hooked. But he evaded bouncers as serenely as he went about every other task on and off the field, without haste or any semblance of panic. And when he executed the late cut, his grace reached the level of the sublime.

While most of the many, many words on Worrell written by CLR James are rendered dubious by the obvious political agenda of that celebrated author, there is one description which does capture the batting of Worrell in a nutshell: “There was no memory of anyone scoring runs in every class of cricket with such grace and power.”

However, the 1954 series against England was the peak of his batting career, after which his numbers deteriorated steadily till the end of his Test career. It started when the Australians visited in 1955 and his elegant bat had a terrible time, a string of single digits marking an unimpressive sequence of innings. The West Indians were pulverised by Lindwall and Miller and only Walcott stood amongst the ruins to fight back.

When Worrell went back to his favourite fields of England in 1957, he started with 81 in the opening Test at Birmingham and followed it up with 191 not out at Nottingham. However, the bats and pads of Peter May and Colin Cowdrey turned the tables on the West Indian spin duo of Ramadhin and Valentine. And apart from the two knocks Worrell was not able to recapture the sparkle of supremacy of his earlier tour. England won comprehensively. However, at Headingley, Worrell did produce the best spell of bowling in his career, capturing seven for 70 in the English innings.

The unparalleled captain

Worrell stayed back in England after the tour, pursuing his degree in Economics at the University of Manchester. He played very little First Class cricket during the next couple of years, but the hiatus was important in the events that followed and the final analysis of his cricket career.

By this time, the Marxist cricket columnist CLR James, editor of The Nation and a major force behind the movement for the emancipation of the blacks, was already lobbying for Worrell as captain of West Indies. Gerry Alexander, the man at the helm, had done an admirable job, but the chorus for a black man at the helm was growing louder by the day.

When Worrell returned to cricket after his studies, he was older, wiser, even more dignified and by far the most experienced player in the side. Weekes and Walcott had retired after the 1957-58 series against Pakistan which had seen Garry Sobers emerge as the brilliant new batting star. Walcott did return for just a couple of Tests against England, but they were insignificant trickles at the end of a great tidal wave of a career.

England visited in early 1960. Alexander was still at the helm, but Worrell made his claims stronger by returning with a bang orchestrated by the gods of romantic comebacks. He batted almost 10 and a half hours in the first Test at Bridgetown to score 197 not out, adding 399 with Sobers. After that he did not quite recover from the exhaustions of this innings, managing just another fifty in the series. But his 320 runs at 64.00 were enough to spur his supporters on to frenzy. Moreover, England won the series, and as a result the axe finally fell on Alexander’s leadership.

Hence, on that historic tour of 1960-61, Frank Mortimer Maglinne Worrell led the West Indians to Australia to contest what has gone down as arguably the greatest series ever played. At 36, Worrell was past his best with the bat and the ball. But as a captain he was extraordinary.

The differences between the islands, the rivalries between the cricketers — Sobers and Rohan Kanhai in particular — were resolved and removed with infinite grace and an ever-present sense of humour. Before the series, the captains, Worrell and Richie Benaud, agreed on positive cricket and a spirit of sportsmanship. No half volley went unpunished, no bowler dragged his feet while returning to his bowling mark. When Sobers appeared to show his dissent after a decision, Worrell spoke to him with his mixture of charm and polite persuasion. From then on, every West Indian batsman walked as soon as the umpire’s finger went up. The contests that followed produced cricket at once colourful and riveting, adventurous and attacking. After the drab years of defensive batting, slow over rates, negative lines and onus on survival, these Test matches brought the crowd flocking back to the grounds.

The first match was the epochal Tied Test at Brisbane, making history in indelible marks in the annals of cricket. After a fluctuating last day, when the final over was bowled by Wes Hall, all four results were possible. As the fast bowler walked down to Worrell to ask his advice, Worrell, supremely calm in those volatile moments, reminded him, “Whatever you do Wes, don’t bowl a no ball. They won’t allow you back in West Indies.” A mixture of wisdom and humour in the heat of that nerve wracking moment. It was perhaps one the greatest man managing manoeuvres ever witnessed on the cricket field.

Worrell himself had a decent time with the bat, with five half centuries in the series, and some useful wickets at Adelaide. His captaincy remained attacking, shrewd, unrelenting — yet his manner never lost its charm. The tour ended 2-1 in favour of Australia, but Worrell and his men were given a farewell no touring side has ever received before or since.

A year later, Worrell led West Indies to a 5-0 win over India at home. The visiting batsmen had no answer to the express pace of Hall, the spin of Lance Gibbs and the variety of styles of Sobers. Worrell headed the batting averages with 332 runs at 83.00.

In the first 1960 Bridgetown Test, Frank Worrell (left) scored 197 not out and added 399 with Garry Sobers. The above photo shows Worrell and Sobers coming out to bat in the 3rd Test against England at Trent Bridge, Nottingham in July 1957 © Getty Images

The legend of the man gained another immortal dimension in the tour game against Barbados. Indian captain Nari Contractor was struck on the head by a Charlie Griffith snorter and fractured his skull in a near fatal injury. It was Worrell who was the first to donate blood, that went along to save the life of Contractor. Since then, ‘Frank Worrell Day’ is celebrated annually at the Eden Gardens in Kolkata, a day when hundreds of people turn up to donate blood. In 2009, such a drive was started in Trinidad as well, inaugurated by Contractor himself.

Worrell’s last triumph was the tour of England in 1963. It was another fantastic series and West Indies triumphed 3-1. He himself did not do much with either bat or ball. On the field he was distinctly slower, although he did run out Derek Shackleton in a curious race between two 39-year-olds during the last stages of that humdinger of a Test at Lord’s.

But his influence over the side as captain was once again remarkable. Yet again, at Lord’s, when Hall bowled another over with the game hanging on a knife’s edge, his advice was simple. Don’t bowl a no ball. Once again, the visitors proved extremely popular. George Duckworth believed that “no more popular side has ever toured in the old country”. The Lord Mayor of London summarised the team led by Worrell as: “A gale of change has blown through the hallowed halls of cricket.”

The final analysis

Worrell retired at the end of the England tour, with 3,860 runs at 49.48 with nine hundreds from 51 Tests. As a bowler, he captured 69 wickets at 38.72 with two five-wicket hauls. The numbers tapered off towards the end of his career, but he knew that he had a role to play as a leader of the West Indian team and his people. And he played it to perfection.

It is his record as captain that stands out as incredible. In his 15 tests at the helm, he won nine, lost three, drew two and tied one. He is still the third most successful skipper in the history of West Indian cricket.

The untimely death

On retirement, Worrell became Warden of Irvine Hall at the University of the West Indies, and was appointed to the Jamaican Senate by Sir Alexander Bustamante. He remained a vocal supporter for closer political union between the nations of the Caribbean. Some of his views were unpopular and criticised widely, but he stood by what he believed and accepted the barbs with his celebrated grace and dignity.

Worrell remained in contact with cricket as manager and selector. His successor as West Indian captain, Garry Sobers, wrote about Worrell’s political acumen when dealing with the vested interests of the different islands. Amidst all his composure and charm, Worrell remained a worldly-wise man who could be very calculating at balancing the pros and cons and making optimal decisions, playing hardened politicians at their game. Sobers, with his political naiveté, was both surprised and relieved by Worrell’s interventions.

Worrell managed the West Indian side during the 1964–65 visit by Australia, and accompanied the team to India in the winter of 1966–67. The tourists of 1964-65 did raise a lot of issues, and angry words flew about. Worrell absorbed all such problems with dignity and smoothed many feathers with astute and experienced hands. His diplomacy, like his batting, seldom countered force with force.

It was while in India that he was diagnosed with leukaemia. He passed away after a short battle with the inevitable in Jamaica, a month after his return from India.

The respect with which the man was held around the world was evident at the reactions to his death. Thousands mourned in the Caribbean islands, in Jamaica where he worked, in Barbados from where he hailed, and in the other islands where he was worshipped as a symbol of the people. Worrell had played a lot of cricket for Radcliffe in the Lancashire League. As early as 1964 a street near the cricket ground had been named Worrell Close. Now, the flag at the Radcliffe Town Hall was at half-mast on the day of his death

.

The Frank Worrell Trophy is fittingly awarded to the winner of the Test series between Australia and West Indies. The University of West Indies Ground at St. Augustine, Trinidad and Tobago, was later renamed Sir Frank Worrell Memorial Ground. And strangely for a cricketer, he has also lent his name to one of the two Halls of Residence at the University of the West Indies, Cave Hill Campus in Barbados. Since 1993, this University has hosted the annual Sir Frank Worrell Memorial Lecture.

Frank Worrell’s face has appeared on $2 stamps and $5 banknotes.

The man behind

While the backdrop of his story remains path-breaking and significant, there was something very human and touching about Worrell as well. Apart from dozing during the most exciting periods of matches, his other endearing flaw was a heavy dose of superstition. It was this strain that made him a tad apprehensive about being the 13th captain of West Indies.

During the 1951 tour of Australia, in the game against South Australia, he was out first ball, caught off Geoff Noblet. Determined to change his luck in the second innings, he shed all his old clothes and donned new ones, abandoning every stitch of clothing and gear tarnished by his golden duck. He walked out in his completely new outfit and was bowled by the same bowler off the very first ball. As he returned, crestfallen, the next batsman Clyde Walcott did not really raise his spirits as he asked with a laugh: “Why do I have to face a hat-trick every time I follow you?”

At that time, Worrell had a finely developed sense of humour that helped him tide over such situations. For the remaining one and a half decades of his life, he sustained this very vital characteristic. In the words of another West Indian cricketing knight Sir Learie Constantine, “He was a happy man, a good man and a great man. The really tragic thing about his death at the age of 42 was that it cut him off from life when he still had plenty to offer the islands he loved.”