Gundappa Viswanath, born February 12, 1949, was an artist with the willow and one of the greatest batsmen produced by India. Arunabha Sengupta looks back at the life and career of the man who remains one of the most loved players in the history of Indian cricket.

The finest innings

He walked in at 24 for two.

By now the little man was used to such situations. It had been the same story in the previous Test at Eden Gardens. Sudhir Naik had been caught off the very first ball of the match. Gundappa Viswanath had trotted out with the side reeling at 23 for two and had gone onto top score with 52. In the second essay, two wickets had gone down for 46 as India had tottered at a crucial juncture against Andy Roberts, Bernard Julien, Vanburn Holder and Lance Gibbs. Already 2-0 down in the series, another capitulation would have rendered the series lost and dead. In the burning situation of crisis, Viswanath had struck the ball with characteristic grace to score 139. India had emerged victorious by 85 runs in a thriller of a Test match.

There was indeed a sense of déjà vu, as he now emerged from the pavilion at Madras. The pitch was slow, but uneven. Roberts was making the bouncers fly at different levels, alternately threatening life and limb. At the other end, Julien had struck twice, removing Farokh Engineer and Eknath Solkar.

Before Viswanath could settle down, Anshuman Gaekwad and captain Mansur Ali Khan Pataudi left in identical ways. The variable bounce of Roberts pushed them on the backfoot and then two full deliveries thudded into their pads in front of the wicket. It was 41 for four. Ashok Mankad, not too comfortable against the quickest, now joined Viswanath at the crease.

Roberts now charged in, bowling full steam to Viswanath. The ball was just short of a length, climbing into the little man. The diminutive Karnataka batsman swivelled in a languid flow, the bat came through in a smooth horizontal arc. Seldom has the hook shot, a weapon of destruction, looked such a thing of beauty. The ball rocketed to the square leg fence. Viswanath ended with his right foot in air, the left pinned on the ground like the sharp end of a compass, the bat on its way to the follow through with the wrists rolled to perfection — a picture of artistry in the face of crisis that made its way to multiple papers the next day.

But, it was just a snapshot of the continuous flow of brilliance. The next ball was pitched up, and the magical wrists worked again. The timing was crisp, the arc of the bat scripting poetry in motion. The ball sped to the mid-wicket boundary. Roberts stopped in his tracks and followed the disappearing blob with a quizzical expression. He was taken off.

With both the opening bowlers having finished their initial burst, Ashok Mankad and Viswanath saw India to lunch with the score a still precarious 74 for four.

After the break, Roberts roared back. Mankad was dismissed without any addition to the score. An over later, Madan Lal had his stumps flattened. It was 76 for six, and the end loomed disconcertingly near. At this stage Viswanath was on 19, with all the indication of a sublime flower about to be left to wither without care and attendance.

But, Karsan Ghavri was a capable man in such situations. And Viswanath made his intentions clear by essaying an almost magical cover drive off Roberts. The crack sounded like a rifle shot.

A bemused Clive Lloyd now concentrated on the other end, using Roberts in short bursts. But, Viswanath continued in the same vein, bringing out that famed square cut, with every ounce of his little frame put into the stroke.

Forty one runs were put on for the seventh wicket before Roberts went past Ghavri’s bat and rattled the stumps. Three balls later, Erapalli Prasanna snicked him to the wicketkeeper. It was 117 for eight, with only Bishan Singh Bedi and Bhagwath Chandrasekhar to come. Viswanath was on 43.

Now, the Karnataka batsman proceeded to farm the strike. The malleable wrists worked the ball around to pinch singles. Bedi stood firm, and Viswanath caressed his way past 50, continuing his innings with sustained brilliance. Another 52 were added for the ninth wicket before Gibbs spun one past Bedi’s defence. Viswanath was on 77. Chandrasekhar, probably the worst batsman in the history of the game, joined the genius at the crease. Even he was inspired by the amazing act to produce a creditable feat of determination. Tea was taken at 175 for nine with Viswanath on 83.

After the interval, Chandrasekhar defended with pluck and fortune, cheered vociferously by the 50000 strong crowd for every ball he survived. Viswanath struck the ball at will, into gaps that seemed to open up for him. With silken grace he moved into the 90s. And with this little champion a stroke away from a masterly century, Roberts made one rear up to the leg-spinner. Chandrasekhar helplessly fended it with his bat in front of his face. The ball flew to Lloyd at gully. Roberts finished with seven for 64. The innings ended at 190. Viswanath remained unbeaten on 97. The next best score was 19.

As Viswanath walked back with an apologetic Chandrasekhar, the crowd rose as one to applaud the hero. Every soul who was lucky to be in the ground that day had been touched by a special brand of magic, one of the most beautiful chapters of Indian cricket, forged by the scorching fire of crisis.

Viswanath followed it up with a four hour effort of 46 in the second innings before the three great spinners bowled India to a historic win by exactly 100 runs. The effort in the first innings remains one of the greatest innings ever played by an Indian batsman.

Viswanath got 95 in the decider at Bombay, taking his tally of runs in the series to 568 at 63.11. But, the home side did not win. Lloyd struck 242 and Holder destroyed the Indian batting in the second innings to clinch the series 3-2.

The loved one

Gundappa Ranganath Viswanath remains one of the most loved of Indian cricketers. Be it the heady concoction of bewitchment and finesse in his stroke-play, or the simple amiability of his personality, he was the darling of the crowds during his playing days and has remained so ever since.

His career overlapped almost in its entirety with the other little great man of Indian batting —Sunil Gavaskar. They remained the closest of friends, even connected in the family tree with Viswanath marrying the sister of Gavaskar. Many an Indian innings was built on the foundation of these two maestros. And for many, including some serious writers of the game, Gavaskar remained true to his batting position — the head of the Indian team, while Viswanath became the heart that throbbed in the middle.

Gavaskar’s perfection led many an Indian cricket follower to look at his feats with something approaching suspicion. Indian cricketing history was unaccustomed to the trait of consistency. In all his success, there was a streak of ruthlessness about the man which was difficult to identify with. He was too correct, too straight, too perfect. He invoked respect, awe, and finally that niggling of that uneasiness that provokes fans to dig deep to unearth a flaw. Did he only score on good wickets? Did he fail when the situation got demanding? Was he too concerned about his records? Was he too commercially minded?

Viswanath was much closer to the hearts of the Indian public. They understood a man who was an obvious mix of phenomenal talent and palpable human weaknesses. He would carve the most lethal of bowling into artistic masterpieces of innings, and at the same time get out cheaply to curious dismissals and toothless adversaries. Viswanath’s artistry delighted the common man, whereas Gavaskar’s copybook approach held joy more for the connoisseurs of technique. And the former was known to be heroic in the face of disaster.

Conclusions were drawn, even respected journalists falling prey to the dictates of the heart and popular appeal. One such reputed pen wrote, “Gavaskar plays for himself, Viswanath plays for India.” This should not surprise anyone. We see such rather irresponsible, unqualified and statistically unverified statements across all media even today, with Gavaskar and Viswanath replaced by modern day icons.

This is not a place to discuss the pros and cons of this trait of the Indian cricket circles and the huge media space looming over it. The relevant message is that Viswanath had that sort of appeal. He was simply adored.

The first and last time I witnessed the master batsman live on the cricket ground was in a low key Wills Trophy Final at the Eden Gardens in 1987-88. Karnataka was playing the Board President’s XI in the title round and Viswanath was in his state team, scheduled to bat at his habitual number four.

By then, he had been out of the Indian team for half a decade. A couple of seasons earlier, his vow to return to the Test side with a gamut of runs had not quite come off. The once lithe form had been spreading too rapidly around the middle. Evidently he was playing his last match at the ground. A fair amount of spectators had assembled in the Club House to watch the last act of the wizard.

When Karnataka fielded, Viswanath remained in the ground as long as it was deemed necessary to keep a slip. As soon as the field spread he walked back, disappearing into the comfort of the pavilion. WV Raman and Shrikant Kalyani plundered the Karnataka bowlers to post 249 in 47 overs.

The maestro walked out to bat at 51 for two. There was a generous round of applause as he traced his way to the wicket. The sprinkling of elderly men, misty eyed in recollecting his heroics in the days of yore, had already spotted a kid sitting there, watching the match alongside their venerable selves. Hence I was subjected to many tales of his greatness, some of which later failed to fit into the stringent dimensions of facts when cruelly evaluated against the dry pages ofWisden. But, the immense popularity of the man, even years after his long omission from the Test side, was something special to behold.

He faced just one ball that day. Young Rashid Patel could be quick on occasions. The ball was short and slightly wide. Viswanath flirted with it, the bat almost horizontal. The ball took the inside edge and crashed into the stumps. There was a pause before he made his way back to the dressing room. The remarks ranged from the sad but affectionate “The same old Viswanath, dragging a wide ball to his stumps” to the diehard fan’s “Even when he is bowled he looks a treat at the wicket.” The Club House rose to applaud him as he walked out of this ground of his many heroics for the very last time. The hero had failed, but he still conjured fondness in the hearts. He was a hero of the people.

Too short to play?

Born in Bhadravati, Mysore, Viswanath’s family moved to Bangalore when he was just five. His interest in the game was pricked as he watched his brother Jagannath and neighbour S Krishna — both good club players.

Jagannath, a great fan of Australian cricket, used to wake him up early to listen to the Test match commentary from Down Under. Viswanath saw little of Neil Harvey, the great left-handed Aussie batsman. Nevertheless he grew up idolising the man by listening to his exploits.

At the Visweswarapuram Middle School and later Fort High School, Viswanath did his bit with the bat. However, short and thin, he never made it to state schools cricket. Hence, he plied his trade at the Spartan Sports Club in the third division of Mysore Cricket League. Watching from the sidelines was the experienced journalist KN Prabhu. He astutely observed that the carefree approach towards batting was based on a foundation of excellent technique.

Some good scores in the P Ramachandra Rao Memorial Trophy brought Viswanath in running for the state side. And heads turned with extreme rapidity when he made his Ranji Trophy debut in 1967.

Playing for Mysore against Andhra Pradesh at Vijaywada, Viswanath ended his first day in First-Class cricket unbeaten on 209. The next morning he took his score to 230 from five and a half hours with 33 fours and a five. It was a new record for the state, going past V Subramaya’s 213. It also bettered the highest score by a debutant in Ranji Trophy, beating George Abel’s 210 for Northern India against the Army in 1933-34.

His second First-Class century took a while in coming. Once again scored against Andhra Pradesh, it was essayed in 1969 and catapulted him into the Indian Board President’s XI against the visiting New Zealanders. Coming into bat at 28 for three, the young man added 99 with the veteran Chandu Borde and ended up scoring 68 in five hours and ten minutes. That very same day, he was added to the Indian team as the 15th member.

He did not make it to the final eleven, but he did not have to wait much longer. A month later, he made his debut at Kanpur against Bill Lawry’s Australians.

Duck and hundred on debut

His first foray on the wicket was hardly auspicious.

In the first innings, Alan Connolly gave him a torrid time. Two bumpers unsettled him and captain Mansur Ali Khan Pataudi at the other end could not really shield him from the seamer. The youngster, terribly ill at ease, spooned up a catch in Connolly’s next over for Ian Redpath to pounce on at short leg. As he sat crestfallen in the dressing room, his captain told him, “Relax, don’t worry, you’ll get a hundred in the second innings.”

On the fourth afternoon, the little fellow walked in again, at a critical juncture. Trailing by 28 in the first innings, India had reached 94 for two. Connolly looked threatening again, having already accounted for Farokh Engineer and Ajit Wadekar.

The large crowd at Kanpur braced itself for another second innings collapse, similar to the one witnessed in the first Test. But, the diminutive youngster stood tall on that day. Connolly’s burst was overcome, Graham McKenzie negotiated with confidence and then Viswanath started dazzling the ground. A couple of delectable drives on both sides of the wicket set the tone. It was all crisp timing, and the Green Park was enthralled — this was definitely something special in the making.

That day Viswanath played every stroke as if painting a precious masterpiece on green canvas. Even a defensive push was a sight for sore eyes. When he drove or flicked, he never hit the ball, but gently guided it on its way. It was while essaying the square-cut that every ounce of his little frame went into the wallop, sending the ball screaming through the crowded point area.

At the end of the day, India had reached 204 for five, with the debutant still there on 69.

The sports pages of the next morning were dominated by a penalty kick taken on a soccer field thousands of miles away. Against Vasco da Gama, the Brazilian genius Pele had scored his 1000th goal on November 19.

Yet, to a nation deprived of sporting stars, their own horizon looked brighter than ever. Viswanath had not only charted India’s route to safety, he had done so by batting beautifully. The Indian Express screamed “Hail Viswanath. He is the new star that has arrived to brighten our cricket horizon.”

November 20 was his and his alone. That morning, he moved to 96 with the same fluent elegance before suddenly going into a shell of scoreless-ness. For the next 20 minutes, only a couple of singles resulted from his bat. And finally, he drove Connolly hard and square through the packed offside field for a sparkling boundary to the roar of the crowd. The hundred had been reached in 282 minutes with as many as 19 boundaries.

He was also the first man to score a duck and a hundred on debut. Andrew Hudson and Mohammad Wasim have achieved this mixed feat since then.

Viswanath reached 137 in close to six hours with as many as 25 boundaries before Ashley Mallett trapped him leg before. As he returned to a standing ovation from a full house of delighted spectators, the score read 306 for seven and the last threat of defeat had been removed.

A hero had emerged who would bat his way through crisis again and again, every time the artist, producing glittering gems in the bleakest of circumstances.

Lt Col VR Mohan, an industrialist in Lucknow, announced the reward of three gold medals worth Rs.1000 each for Viswanath, Ashok Mankad and Paul Sheahan for their performances in the Kanpur match.

The period of fluctuations

Till that time, no Indian centurion on debut had ever added a second ton to his record. It looked quite inevitable that Viswanath would be the one to break the jinx. But it did take time in coming.

After two more fifties against the Australians in his debut series, Viswanath took a while to settle down as the permanent number four in the Indian line-up. In the triumphant West Indian tour that followed, Gavaskar emerged as the great new hope of Indian cricket. Suffering from a wrenched knee early on the tour, Viswanath went through a rather less successful time, scoring 135 runs at 27. Neither of them set the grounds of England ablaze when India won a historic series in the summer of 1971.

Back home in India, both Gavaskar and Viswanath contributed little as India won two of the first three Tests against Tony Lewis’s England in 1972.

However, while many feared that Viswanath was doomed to suffer the same fate as the other Indian centurions on debut, there were always glimpses of bristling talent beneath the failures. Finally he scored an unbeaten 75 at Kanpur helped to bat out time in the fourth Test against England. The following Test was at the Brabourne Stadium in Bombay. It was his 15th match and three years since his debut. Viswanath hit 113 to overcome the shadows of the past and quack numerology. In celebration, the huge Tony Greig picked him up and cradled him while singing a lullaby.

The best phase

Yet, it was the series against West Indies in 1974-75 which established Viswanath as the world-class batsman who could carry the team on his shoulders. Some phenomenal knocks followed in the next few years.

His 112 at Port of Spain did much to secure the famous victory after India had been set 404 to win. It was also the match in which he showed the new inclination to loft spinners over the infield.

He hit five delightful fifties in the closely contested 1977-78 series in Australia against the Packer depleted side led by Bobby Simpson. And in the disastrous series in Pakistan that followed, he started off creaming 145 against Imran Khan and Sarfraz Nawaz.

There were two hundreds against Alvin Kallicharran’s West Indians at Madras and Kanpur in 1979. The Madras knock was another superb innings on a fast, bouncy wicket which went a long way to ensure victory for the Indians.

After two rather disappointing voyages to England, he finally came good in 1979, with a century at Lord’s and three fifties to boot. The Lord’s hundred saw him add 210 with fellow centurion Dilip Vengsarkar and save the Test from an almost impossible situation.

Two more hundreds followed when Kim Hughes led another depleted Australian team to India in 1979-80. By the end of the victorious series against Australia, Viswanath had 4759 runs from 62 Tests at 47.11 with 11 centuries.

No one questioned the visual and aural delights associated with his sublime wrist-work and timing. However, the figures testified more than that. There had been the occasional failures, in England in 1974 and against the same team at home in 1976-77. But, by now he was one of the very best batsmen in the world. Indeed, he showed signs of maturing towards that elusive trait in Indian batsmen — consistency. Along with Gavaskar at the top and Vengsarkar at number three, the Indian line up looked set to become one of the best in the world.

A tale of two Tests of captaincy

The amazing success of the last few seasons had also made a few believe that Viswanath was ready for bigger and greater things. One among these believers was Gavaskar.

At this point of time, the master from Bombay almost ruled Indian cricket. As captain and legendary opener, he could run the team according to the dictates of his will. It was mainly his idea to step down from captaincy during the final Test against Pakistan in early 1980, and the Jubilee Test against England the very same year. Viswanath led India in those two Tests.

Sadly, it was not exactly a fruitful experiment. First of all, the amazing run of success had ended for Viswanath. After a 75 at Bangalore in the first Test against Pakistan, Viswanath had already started out on a two year, 14 Tests and 25 innings which would see only one 50-plus score. Yes, the substantial score during this period was the celebrated 114 at Melbourne against Dennis Lillee and Len Pascoe in another stupendous victory over Australia. But, what often passes unnoticed is that this classic innings was played during one of the worst phases for the master batsman.

Secondly, captaincy did not agree with him. Asif Iqbal’s fishy behaviour at the toss, followed by his sudden declaration while way behind on the first innings, was not really ideal for a man of Viswanath’s outlook towards the game. He followed his principles with conviction, calling Bob Taylor back during the Jubilee Test, after the wicketkeeper had been given out by the umpire. His inaugural Test as captain was drawn against Pakistan at Eden Gardens. The Jubilee Test was lost at Wankhede stadium, mainly due to Ian Botham’s brilliance and somewhat because of his own old world spirit of fairness. He seemed a much relaxed man when the sceptre was handed back to the worldly-wise Gavaskar.

Melbourne magic

Yet, he had somehow lost his touch with the bat. The subsequent series in Australia, against a home team strengthened by the return of the Packer stars, saw him struggle for runs.

And then came Melbourne. In the final Test, for four and a half hours the clock was turned back. As the rest of the batsmen fell to Lillee and Pascoe, Viswanath came in at a familiar 22 for two and stroked his way to a gem of a century. Syed Kirmani’s 25was the next highest score, and India totalled 237.

They trailed by 182 in the first innings, but snatched a historic win after setting a target of 143. Yet again, Viswanath had played a stellar role in extreme conditions.

However, during the New Zealand leg of the series, his problems returned with a vengeance. The tour saw him manage just 64 runs at 12.80.

The last days

It was not until the tedious home series against England of 1981-82 that he returned to form. In a monumental bore of a Test at Delhi, he hit 107. After struggling in the following Test at Calcutta, he hammered his career best score of 222 at Madras — adding 316 with Yashpal Sharma. Vishwanath ended the series with 74 at Kanpur. There were signs and symptoms that he was back at his very best.

In the tour to England that followed in the summer of 1982, he failed in the defeat at Lord’s but struck three half centuries in the two other Tests. The final innings of 75 not out at The Oval came out of a total of 111 for three, after two wickets had gone down for 18.

The two fifties at The Oval reassured everyone that the cricketing god was very much in heaven and the strokes still dazzled from the divinely gifted bat. However, the willow had just flattered to deceive.

The decline had started for a while and soon became increasingly prominent. He struggled in the two innings against the inexperienced bowling of Sri Lanka in the first ever Test match between the two countries. The resulting scores were nine and two.

The end however hastened in Pakistan. He looked all at sea against Imran and the other Pakistani bowlers. His discomfort was conspicuous in the second innings of the second Test at Karachi when he shouldered arms to a vicious Imran delivery that dipped back and uprooted his stumps for a duck. He became the 200th wicket for the iconic all-rounder.

By the final Test at Karachi, his form had forced the team management to push him down the order to number six. Ravi Shastri was promoted to open the innings and scored a century. In rather favourable conditions for batting, Viswanath struggled for an hour and forty minutes to score 10 before losing his stumps to Mudassar Nazar. It was painful to watch the once sublime batsman struggle in this way.

His fans were thankfully spared the agony. Viswanath was dropped from the side bound for West Indies and never made it back to the national team. He did enjoy a couple of good seasons in 1984-85 and 1985-86, but there was no place available for him in the crowded Indian middle order.

Viswanath’s career ended with 6080 runs from 91 Tests. His average, once in the late 40s, had come shooting down with great haste, but still finished at a respectable 41.93. He scored 14 hundreds, four in victories and the remaining 10 in stalemates. Both his aggregate and number of centuries stood second only to Sunil Gavaskar in the Indian batting charts until Dilip Vengsarkar went past them.

After retirement Viswanath remained very close to cricket. He served for a brief while as manager of the Indian team. He also acted as a match referee for the International Cricket Council (ICC) from 1999 to 2004. Later he became the chairman of the national selection committee. He has also been involved in cricket coaching at National Cricket Academy (NCA).

In 2009, Viswanath was awarded the Colonel CK Naidu Lifetime Achievement Award by the Board of Control for Cricket in India.

An attempt to measure the magic

How great a batsman was Viswanath?

At the risk of trying the impossibility of measuring art, let us attempt to understand how Viswanath’s career panned out down the years.

His stint at the wicket can be divided into four more or less distinct phases. The first period of establishing himself in the side saw his average fluctuate in the 30s before the superb series against West Indies in 1974-75. After that, for the next few seasons, he remained a brilliant batsman prone to sudden lapses of form. Sometimes the troughs could be inexplicable, as in the home series against England in 1976-77. From the Australian tour of 1977, Viswanath hit a purple patch and during a two-year period was one of the finest batsmen of the world. However, as witnessed from the series against Pakistan in 1979-80, he was no longer the commanding batsman he once was, and sparks of brilliance, as in the Melbourne match, came off only on rare occasions.

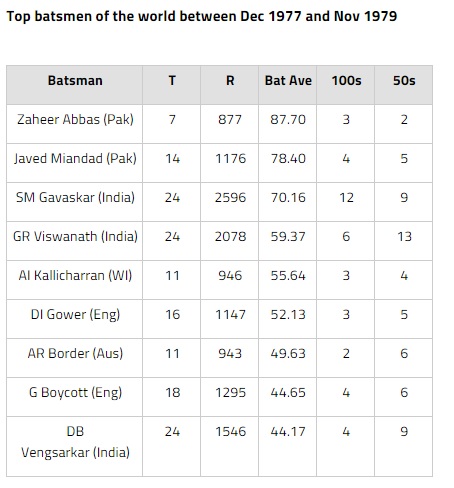

During the purple patch between December 1977 and November 1979, Viswanath was the second highest scorer in the world after Gavaskar. This was obviously helped by the enormous number of matches India played during this period. However, even if we look at the averages, he ends up fourth in the world. It was obviously a period when all the Packer stars were away from Test cricket. But, among those who played, Viswanath was indeed at the very best.

According to his own confession, Viswanath seldom focused on consistency. Hence, rather than eschewing risks, he sought creative expression of his talents. Batting to him was a much more fulfilling matter than the mundane business of run making. Hence, he did not manage to find a place in the same category as the run machines of the era — people such as Gavaskar, Viv Richards, Greg Chappell and Geoff Boycott.

It is a testimony to his immense talent that he still managed to be a world-class performer for much of his career — in spite of his rather mercurial approach.

When lined up against the greatest batsmen of India, his name is spoken in revered tones, often in throes of dreamy nostalgia. He seldom makes it into the All Time Indian XIs, but the consensus is that there will seldom be another batsman of his kind.

That Viswanath played several memorable innings in moments of crisis should be less surprising and more expected. Original and inventive, his style was prone to be sparked to great deeds by the flame of insurmountable challenges. Hence we see him amass the 97 at Madras, the 112 at Port-of-Spain, the 124 on that fast wicket of Chennai in 1978-79,the 113 at Lord’s and the 114 at Melbourne. He had the penchant to succeed when people collapsed all around him, to essay knocks that were invaluable in demanding circumstances. At the same time he often lost his wicket to careless strokes when the situation was markedly easier.

He did not play too many One Day Internationals (ODIs), and was not the ideal ODI batsman. He averaged just 19.95 in the 25 matches he played and crossed 50 just twice. However, even in this format, his highest score was a superb 75 against the lethal West Indian attack in the second Prudential World Cup — an innings in which none of his teammates scored more than 15.

He did not always turn defeats into victories. He did have his share of failures. But, he always remained the one batsman people loved to watch, for the pure, unadulterated joy it always provided. Viswanath was synonymous with artistry scripted with the willow. Whose every movement at the crease carried with it delicious elements of magic.

Years after his retirement, long after the day I had seen him play on to that Rashid Patel delivery, Viswanath was in my city as the manager of Karnataka. And there were a couple of my acquaintances, men belonging to a generation that had seen him in his heydays, making their way to the stadium much earlier than the scheduled start of the match. I heard them say that they did not care about the game. It was about watching Viswanath with the willow while he provided catching practice to his team. Even the sight of the man deliberately edging deliveries to a ring of stationed slip fielders was worth the journey.

Such was the lure of the man, a picture of grace in whatever he did at the crease.