Ian Meckiff, born January 6, 1935, was a left-arm fast bowler with a graceful run up followed by a suspect delivery. Arunabha Sengupta writes about the Victorian paceman whose career came to an abrupt end after being called for throwing in a Test match.

Thrown Out

Ian Meckiff lives on in our memories as the batsman with that desperate lunge for the crease in cricket’s most famous photograph. Garry Sobers and Rohan Kanhai are seen exulting near the striker’s end. Bowler Wes Hall is seen standing at silly mid-off, somehow having reached there in his follow-through. Lindsay Kline looks pensively over his shoulder as he dashes down the pitch. Only Frank Worrell stands serene and unruffled behind the stumps at the non-striker’s end.

We cannot see Joe Solomon in the frame, but it was his throw from square leg that hit the stumps from a nigh-impossible angle. It caught Meckiff short of his ground and completed the first ever Tied Test match in history.

Yet, some years later, when Meckiff named his autobiography Thrown Out, it was not that arrow-like return from Solomon that he was referring to. His connection with the throw went way beyond that — culminating in another Brisbane Test three years later.

In the late 1950s and early 1960s, men like Geoff Griffin, Peter Loader, Charlie Griffith, Jimmy Burke, Gordon Rorke and Tony Lock — to name a few — had combined into a formidable army of bowlers with suspect action. And, among them, Meckiff was singled out by fate to become the most unfortunate victim.

He had a beautiful leisurely run-up, somewhat reminiscent of Ted McDonald. But after the delightful approach, Meckiff’s actual delivery and follow through showed all the symptoms of a chucker. Ian Peebles, who observed him in the nets on the morning of a Test match, remarked “… his action exactly resembled a coach throwing the ball to a young batsman at the net.”

His delivery, appended with a pronounced drag, even led the diplomatic England skipper Peter May to confide to biographer Alan Hill, “Having a ball thrown at you from 18 yards blights the sunniest disposition.”

The unsuccessful young spinner

It is interesting to note that Meckiff actually started as an unorthodox left-arm spinner. Perhaps it also explains the early development of his pronounced and controversial wrist-whip.

As he grew up in Mentone, a suburb in the south-east of Melbourne, Meckiff attended the Mordialloc-Chelsea High, representing his school in athletics, swimming, cricket and football. Elder brother Don also excelled in all these sports, and younger sister Margaret played softball for the school. In due course of time, the two boys started turning out for the Mentone Cricket Club in the Federal District Cricket Association. As a spinner, Meckiff took 200 wickets for the club at an average of 4.50. At the age of 11, he was included in the Mentone Under-16 team.

At 15, Meckiff went for trial at Richmond. His jerky spin, however, left the club selection committee unimpressed. Hence, he switched to bowling quick when he began his district career in Victorian Premier Cricket playing for South Melbourne. In 1952-53, he became a member of the club’s first championship winning side.

As he progressed along the cricketing path, Ray Lindwall and Keith Miller were approaching the twilights of their blazing careers. Alan Davidson was still not a regular in the side. To fill in the urgent requirement for quick bowlers, Meckiff was advised to work on his speed.

At the same time, he remained as versatile a sportsman as in his schooldays. Along with his cricket, he played Australian Rules Football for Mentone in the Federal League, and was in the team that won the premiership in 1956. He also received offers to play in the Victorian Football League, at that time the top-tier competition. He declined so that he could pursue his cricket career.

Later, he also played golf in pennant competition and captained the Victoria Golf Club.

Into top league

Coming back to cricket, by the time he made his First-Class debut for Victoria in 1956-57, Meckiff was genuinely fast — if somewhat erratic. He ended with three for 45 in his first innings — with the special first scalp of the young Bobby Simpson for a duck.

The season saw Meckiff regularly among wickets and early next year he was selected in the Neil Harvey XI against the Ray Lindwall XI — an important fixture for probable Australian cricketers. In the first innings, Meckiff claimed Ken Mackay, Simpson, Norman O’Neill and Graeme Hole in his six for 75. He followed it up with a merry, bat swinging 47 as the number nine batsman. It was one of the very rare occasions that his bat prospered.

Towards the end of the Australian summer, the young fast bowler was taken on a non-Test your of New Zealand. He excelled in the match against Auckland, claiming nine wickets. In the final game against a representative New Zealand side, he finished with outstanding figures of four for 28 from 27.2 overs.

The South African tour of 1957-58 saw a major reconstruction of the Australian team. Miller had called it a day and Lindwall was not chosen. The superbly talented fast bowling all-rounder Ron Archer had his career curtailed due to injury. Meckiff was one of the men chosen as the new guard, becoming one of the four Australian cricketers to make their debut in the first Test at Johannesburg. The 22-year old Ian Craig led the side. Alan Davidson ran in from one end with the new ball, and Meckiff from the other — the unusual novelty of a pair of left-arm fast bowlers. Meckiff claimed five for 125 in the first innings and three for 52 in the second. The Test was a draw, but the rookie bowler impressed with his unsettling pace. He also had memorable moments with the bat, scoring a stubborn 11, helping Richie Benaud to reach his hundred.

However, the excellent start petered out to a disappointing end. In the second Test at Cape Town, he broke down early in the first innings and took no further part in the match. The misfortune caused him to miss the third Test at Durban as well. He came back to capture six first innings wickets against the combined team fielded by Orange Free State and Border and thereby got back to the Test side. However, he was not as impressive in the remaining Tests.

It was a mixed bag for the young bowler, but overall he was considered promising. However, some seeds of future problems were already sown. Umpire Bill Marais came forward a year later to disclose that he was prepared to call Meckiff and part-time spinner Jim Burke for throwing. It was rumoured that Craig got wind of the intentions and had Meckiff and Burke bowl from the other end.

The problems of 1958-59

The problems surfaced when England visited in 1958-59. According to some of the members of the tour, they came across throwers everywhere — from the state teams to the Test matches. Huw Turbervill, author of The Toughest Tour: The Ashes Away Series Since The War wrote: “Australian bowlers were … throwing the ball at the English batsmen at startling speed.” The chief offenders were Gordon Rorke, Meckiff, and the occasional spinner Jim Burke.

According to England batsman Tom Graveney, “Rorke was huge and he threw it at you. There were no crash helmets back then. All you had to do was stand there and fend it off…”

The grumbling started after Meckiff claimed four first innings wickets for Victoria. In a subsequent team meeting, all-rounder Trevor Bailey warned, “This man throws. I can assure you that if nothing is done he will win at least one Test match for Australia.”

However, May desisted the urge to complain. On the tour, the need for diplomacy was paramount. Besides, with Peter Loader and Tony Lock in the side, England were not really well placed to lodge a complaint about throwing.

The five wickets Meckiff captured in the first Test at Brisbane in the Australian win did not go down well with the Englishmen. Jim Laker later wrote in his controversial Over To Me. “I vividly remember batting in the Brisbane Test with Meckiff at one end and Burke at the other. ‘It’s like standing in the middle of a darts match,’ I told Neil Harvey. Neil doubled up. It was about that time that Meckiff had one of his wild spells. Norman O’Neill, from the boundary, sent a fine throw right on top of the stumps. ‘Put Norm on,’ yelled a wag in the crowd, ‘at least he can throw straight.”

When he captured six for 38 against England in the second Test at Melbourne, it raised several infuriated English voices. Journalist EM Wellings wrote, “He runs no faster than Hedley Verity, yet the balls leave his hand at express pace.” Alf Grover claimed he did not bowl a single legal delivery, adding that it was “ridiculous that a player with this action should be the agent of England’s destruction.”

Bailey fumed that he not only threw, but also dragged. “He managed to break the batting crease with his back foot which intimates that he got pretty close to you … Meckiff was the worst bowler ever to represent Australia.”

Later, captain Peter May also voiced: “Englishmen who fell to Meckiff’s speed and lift were hardly happy at being victims of deliveries that began with a bent arm and finished with a pronounced wrist-whip.”

Bailey even filmed Meckiff’s action and the movie was shown to Marylebone Cricket Club (MCC).

Meckiff on his part, maintained that he had a permanently bent elbow. In Thrown Out he writes, “Like most fast bowlers I get most of my pace from my wrist action. Being slightly double jointed in the shoulders … this gives me added strength and power. I have the support of the umpires in five countries.”

The attacks of the English press infuriated the Australians. Skipper Richie Benaud was furious. Former captain Ian Johnson slammed Lock and Loader for their actions. He also charged Brian Statham and Fred Trueman of producing jerky deliveries, claiming that both employed a ‘whip lash’ wrist movement at the point of delivery.

Meckiff suffered an injury in the third Test and was ruled out for the following game. When Ray Lindwall replaced him in the fourth Test, the legend remarked, “I’m the last of the straight-arm bowlers.” Meckiff and Lindwall bowled together in the fifth Test. The Victorian paceman headed the averages for the series, with 17 wickets at 17.17.

He, however, continued to have a torrid time. His parents were pestered by press and public, his wife was continually upset, and even his young son was named Wayne ‘Chucker’ at school. Once, while giving some tips to schoolboys, Meckiff had rolled his arm over, when a kid screamed, “No Ball.” The strain of the series became a bit too much to bear, and Meckiff had to seek medical advice.

The books that were published about the tour also had tell-tale titles. Jack Fingleton wrote Four Chukkas to Australia, while E. N. Wellings penned the mammoth The Ashes Thrown Away. Television programmes were arranged, where journalists like Wellings discussed the issue with the likes of Keith Miller and Sid Barnes.

The change of rule

While the cricket world discussed his action, Meckiff went on a rather ordinary tour of India and Pakistan. He captured seven wickets at Brabourne in the third Test. However, other than that, there were no major successes.

Off the field, a lot was taking place.

At the Imperial Cricket Conference meeting of 1960, Don Bradman was adamant. He was acting as a member of the Australian Cricket Board and also one of the selectors. The issue was so volatile that Bradman himself had been sent to England to attend the meeting instead of the normal British representative. And The Don refused to admit that he had picked bowlers with illegitimate action. Interestingly, the one who locked horns with him on this touchy issue was his old adversary of the 1930s, Gubby Allen.

As Allen remarked later, “He wouldn’t budge an inch and neither would I. He said Australia had no chuckers and I said that was rubbish … I had film of some of the worst offenders, but Don and the other Australians would not look at them. But deep in his heart he knew they had a problem …”

It was the way this problem was tackled that left a lot to be desired.

In the 1960 conference, the throwing law was changed to forbid the straightening of the arm at the instant of the ball’s delivery. However, the interpretation remained variable.

During the 1960-61 season, the Victorian bowler ran in as usual and was not called. He took part in two Tests of the great series against West Indies and, although not really successful with the ball, made himself immortal with his desperate scramble in the last ball of the Tied Test. After the series, he ran out of form and also had his share of recurrent injuries. As a result, Meckiff did not go to England for the 1961 Ashes tour.

The 1963-64 series was the first Australia played after the retirement of Alan Davidson. As a result, there was a giant void to be filled. And as the leading wicket-taker of the 1962-63 season, Meckiff was the man to step into the giant shoes. At the same time, the Australian Board of Control had issued a directive asking umpires to “get tough” in enforcing laws of cricket.

In the first two Sheffield Shield matches of the season, Meckiff took 11 wickets — most of them important ones. He was called as well — once in each match. And in spite of that he was selected for the first Test against South Africa at Brisbane.

The South Africans under Trevor Goddard were supposedly stunned by Meckiff’s selection. They believed his action was illegitimate. Across the world, the selection was met with hostility — especially in England. With the Ashes to be played for in the summer of 1964, the thorns came out and the press became vocal. In the News of the World, Colin Ingleby-Mackenzie wrote: “There is no room in cricket for throwers. Let us hope that…the Australian selectors realise this…otherwise the throwing war will be waged in earnest.”

At home, speculation was rife that the bowler was chosen so that he could be no-balled in a high profile Test match — thus improving Australia’s anti-throwing credentials. According to Keith Miller, the selection had “peppered this once drab-looking series into a curry hot-pot, with all the excitement and trimmings of an Alfred Hitchcock thriller”. The outspoken Bill O’Reilly observed inThe Sydney Morning Herald that Meckiff’s inclusion was “one of the most fantastic somersaults in cricket policies in our time.”

Miller also predicted that the umpires Col Egar and Lou Rowan would have sleepless nights. He added that he hoped that Meckiff was not being used as a scapegoat.

The predictions of Miller turned out to be eerily close to the mark, including the projected dilemma of the umpires. Egar was particularly flustered. Meckiff was a close friend. The duo had won a pairs lawn bowling competition just a few months earlier. However, the fast bowler and the umpire socialised freely at the pre-match function.

At Brisbane, Benaud won the toss and Australia batted. Brian Booth scored 169 and Peter Pollock picked up six wickets as the home side finished on 435. South Africa took strike just after lunch on the second day.

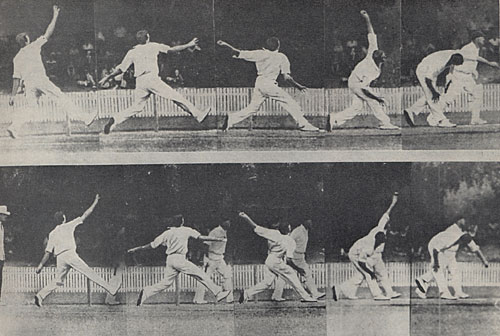

Graham McKenzie bowled the first over and conceded 13 runs. And then came the moment that had the entire cricket world at the edge of the seat. Meckiff started the second over from the Vulture Street End, bowling to Trevor Goddard. At the same time, South African manager Ken Viljoen set up a movie camera and started filming his action.

Egar had officiated in three Sheffield Shield matches and two Test matches featuring Meckiff and had never had any problem with his action. In fact, he had told his friend that there was no point in changing his action after the rules had been modified. He was one of the umpires who had stood in the Tied Test.

Now, standing at square-leg, Egar called the second, third, fifth and ninth deliveries as throws. After the third ball, captain Benaud ran up to Meckiff and spoke to him. After the fifth ball, a full toss struck for four, the bowler and captain spoke again. The same thing happened after the ninth ball. The next three balls were not called and the over was completed.

The rest of the 133.5 eight ball overs in the innings were shared by McKenzie, Alan Connolly, Tom Veivers, Benaud himself, Bobby Simpson and Norman O’Neill.

The crowd stood vociferously behind the bowler all through. Egar was heckled during the infamous over, and before the close of the second day’s play, chants of “We want Meckiff” grew louder. When play ended, spectators entered the field and carried the Victorian off the ground on their shoulders. Egar had to be escorted out by the Queensland Police.

Later Meckiff said that he not bear Egar any grudge. Yet, he added that although the umpire had done what he had thought was correct, the calls had felt like being stabbed in the back — more so because Egar was a close personal friend.

The Test ended in a dull draw — all its excitement provided by the Meckiff affair. At the end of the game, the Victorian pace bowler retired from all forms of cricket. His 18 Tests had brought him 45 wickets at 31.62 with two five-wicket hauls.

Victim of conspiracy?

Several sections of the Australian cricket community believed that Meckiff had been the victim of a conspiracy. At a dinner for the visiting state captains hosted by Bradman in January 1963, it had supposedly been hinted that Meckiff might turn out to be a sacrificial offering. During the evening, Bradman had run a film showing bowlers with suspect actions — Meckiff among them. The legendary batsman definitely had his doubts over Meckiff’s action, yet he was one of the selectors who ensured the fast bowler’s inclusion in the Test side.

Phrases such as “smacks of a set-up”, “obvious fall-guy”, and “sacrificial goat” flew about. Several, including Keith Miller, wanted Bradman to resign. Cricketer-turned-journalist, Dick Whitington reported that Egar and Bradman had travelled from Adelaide to the Brisbane Test together, making it look very much like a plot. It was also revealing that Benaud did not try to bowl Meckiff from the other end.

The Australians played the Test with five regular bowlers apart from Simpson and O’Neill. This fact somehow hinted at prior knowledge of things to follow.

Connolly remained adamant that his teammate’s action was legitimate and the entire incident implied treachery. He said, “I wasn’t amazed …There was a good reason for that, which I can’t disclose and won’t disclose.”

Veivers, who made his Test debut for Australia in that match, said that at the pre-match function, the other umpire Rowan had mentioned, “It’s going to be a very interesting game.”

However, Egar always denied any conspiracy.

Bobby Simpson, in his memoirs, Captain’s Story, branded several cricketers as chuckers, and his list of throwers predictably included Meckiff. In 1965, the fast bowler sued his former teammate for libel. The case ended five years later with an out-of-court settlement and apology from Simpson.

However, Simpson’s famed opening partner Bill Lawry maintained that Meckiff was one of nature’s gentlemen and that his exit was “one of the saddest of my life”. He added that Meckiff was a “pretty fair example of the old expression that good guys run last”.

Alan Connolly remarked: “‘Meckie’ was one of the nicest guys. It was to his great credit that he wasn’t soured by the whole incident.” His words were apt. In spite of all that took place, the affable Meckiff continued to socialise with the cast of characters involved in his last Test, including Simpson, Egar and Rowan — as also the South African vice-captain Peter van der Merwe.

After his retirement, Meckiff worked in advertising, while spending some time in the commentary box. He was quite frequently approached by cricket administrators and lent them all his expertise. However, after the Brisbane Test, he refused to play the game in any form. He did not even roll his arm over on social occasions.