Iqbal Qasim © Getty Images

Iqbal Qasim, born 6 August 1953, was one of the foremost left-arm spinners of his era, whose record speaks eloquently for his quality. Arunabha Sengupta takes a look at the career of the man who played under the shadow of Abdul Qadir most of his life, but ended with figures better than the legendary leg-spinner.

Thriller at Bangalore

Bangalore 1987. It was an elementary error by the master strategist. The great Imran Khan had made a huge blunder.

A look at the pitch had somehow convinced him that it would be helpful to seamers. The legendary leggie, Abdul Qadir, had bowled 68 overs in the series capturing just four Indian wickets at 60.50 apiece. Imran had benched him and lanky left-arm pacer Salim Jaffer had been included in his place. In the end, like the fat slow schoolboy picked to make up the numbers, Jaffer did not bowl a single over and batted at No 11.

So, when Maninder Singh turned it square from the word go and picked up five wickets before lunch on the first day, the Indian fans sported wry smiles on their faces. Pakistan collapsed to 116 all out in less than 50 overs; the pitch was a minefield, and they had left out their best spinner.

Or had they?

Those were the days before the internet. Before cricket statistics were at the fingertips of all and sundry, available at one click of curiosity. Qadir had made headlines and had therefore turned a lot of heads. After all, he was worth plenty of column space — a leg-spinner who approached with a peculiar run up, who turned the ball immensely either way, and who had bamboozled the Englishmen multiple times. For obvious reasons he was far better known than his more sedate and orthodox compatriots.

So, when the belligerence of Dilip Vengsarkar took India past the Pakistan total for the loss of just four wickets, Pakistan showed all the signs of suffering from the mistake of selection and a huge lead was anticipated. And when suddenly the innings fizzled out from 126 for 4 to 145 all out, the air sparked with incredulity. The man responsible for the avalanche of wickets was Iqbal Qasim, capturing four of the last six. He and Tauseef Ahmed had taken five wickets apiece.

Yes, the Indians who always tuned in to the Sharjah tournaments knew that Tauseef could be a tough customer. But, what was so special about Qasim? He had been out of the side for two years since early 1985, and had been recalled only in the Jaipur Test of the current series. And almost immediately Krishnamachari Srikkanth had hit him out of the ground. Old timers recalled that he had been to India before. Yes, he had got wickets in 1979, quite a few of them at Wankhede. But, Pakistan had lost. The Indian spinners had been better.

Qasim bowled some tidy left-arm spin, approaching the wicket in very staid, unremarkable, angular steps between the umpire and the stumps. His action was flat, often pushing the ball fast through the air. He was accurate without being overly impressive.The Indian supporters shrugged and put it down to luck factor. They still led by a small margin, and had three spinners to pry open the little gap and create the differentiating chasm.

And by the end of the second day, Qasim had proved to be more than just a stereotypical left-arm spinner. He had been sent in at No. 5 by Imran and had proved to be a steadfast, stubborn batsman. He added 32 with Saleem Malik and 21 with Imran, batting over an hour before falling for 26. His innings was invaluable in the low-scoring match that hung on the edge of a knife.

In the end, India were left with 221 to win. They ended the third day at 99 for four, Sunil Gavaskar and Mohammad Azharuddin at the crease. And after a brief period of rising hope, Qasim struck four times in a row. Azhar turned the face of his bat to play it past mid-on and the bowler held the leading edge. He held it back to Ravi Shastri, and the tall all-rounder perished by chipping it back to the bowler. Kapil Dev was bowled by one that turned just the right amount. And finally, Gavaskar’s fascinating vigil of 96 runs was brought to an end when a ball cocked up and went to slip.The great Indian opener walked back for the last time in a Test match. Perhaps it did not touch the bat, perhaps it did. But Pakistanis did believe that he had been leg before to Qasim twice before that. The umpire’s finger did rise this time and the Indian hearts sank. The challenge ended at 204, the two spinners taking four wickets apiece.

The Indians could not believe it. After the great stroke of luck with Qadir’s omission they had been done in by the guiles of two bowlers who possessed little of the hype and threat that was carried by the persona of the intriguing leg-spinner.

Very few were aware that Iqbal Qasim possessed a better career record than Qadir. In fact, so did Tauseef — although his career was too short to allow reasonable comparison.

Even now, very few are aware that Qasim ended his career with numbers better than most of the vaunted spinners of his era. His career had begun more than a decade back in Adelaide. After the high of Bangalore, he played two more seasons, capturing 22 wickets at 20.27. One of the following five-wicket hauls was submerged in the sound and fury that swirled about between Mike Gatting and Shakoor Rana. However, in his last season, he took 8 wickets (Qadir 5, Tauseef 3) in Pakistan’s victory against Australia at Faisalabad.

Supremacy in numbers

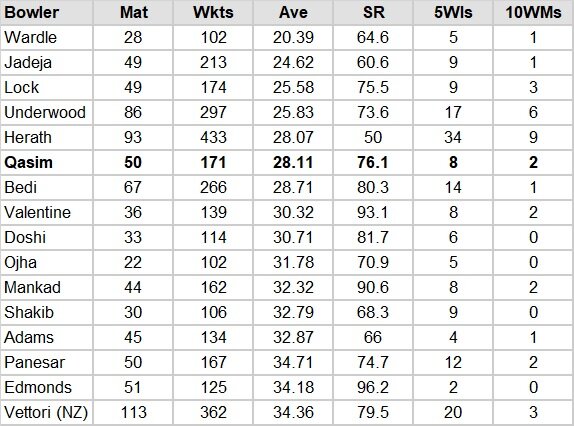

For some surprising reason, Qasim is seldom remembered as a great left-arm spinner. Surprising, because the figures scream his supremacy over many acclaimed names.

Among left-arm spinners who have played their cricket after the Second World War, Qasim is at number six after Johnny Wardle, Ravindra Jadeja, Tony Lock, Derek Underwood and Rangana Herath. He has a better average and strike rate than luminaries such as Bishan Bedi and Alf Valentine.

Left-Arm Spinners since WW 2

if we consider the three decades from the 1960s to the 1980s, we cover a golden age of spin bowling. It was the period when the Indian spin quartet ruled the world — or at least we claimed they did. This was when the tall form of Lance Gibbs loomed over the bowling crease for West Indies.

*If we consider the full career of Gibbs, he took 309 wickets at 29.09 and a strike rate of 87.7 in 79 matches.

Even in such august company, we find Qasim to be just behind Underwood. Difficult as it may be to digest, Qasim scores over Bedi and Gibbs in terms of both average and strike rate.

And if we look at the many riches of spin bowling in the annals of Pakistan cricket, we find only Saeed Ajmal boasting a marginally better average than Qasim. Given that Ajmal is still tweaking the ball in Test matches, there is every possibility that this average may go down to settle beneath the left-armer. Qasim remains the only left-arm spinner of Pakistan to capture more than 100 Test wickets.

In spite of his impeccable figures, Qasim’s feats are rarely recalled. And if they are, the reasons for reminiscences go beyond his bowling abilities.

The gutsy debutant

Several excellent spells for the National Bank of Pakistan propelled Qasim into the national side to tour Australia in 1976. His performance on Test debut at Adelaide was remarkable for a number of reasons, but it was his gritty show as a batsman that attracted more attention than his bowling. He came in to bat in the second innings at No. 11, the lead paltry and plenty of time left in the game. And he batted for 96 minutes against Dennis Lillee, Garry Gilmour and Kerry O’Keefe. Qasim scored just 4, but his stand with Asif Iqbal was worth 87. It left Australia with just less than enough time to get the required 285. Qasim himself went a long way in thwarting the Aussie attempt, ending with 4 for 84 in 30 overs as the hosts finished at 261 for 6.

Seven wickets followed in the second Test, but Australia won by a huge margin — rendering his efforts unremarkable for no fault of his own. And in the final match at Sydney, he hardly got a chance to bowl as Imran routed the Aussies with 12 wickets.

He had made a mark as a gutsy, fighting player and was to be a regular in the side for almost a decade. But, he did not achieve the spectacular star turn that would have made him an immediate talking point. His deliveries were too naggingly accurate and he did not turn the ball much. He depended way too much on subtle changes of speed and trajectory. There was nothing glaringly spectacular about his bowling, and perhaps that is why he remained a gallant performer who was not quite spoken of in the same terms as the rest of the great spinners of the era.

He might have become a hero of the nation when he captured 10 wickets at Bombay in 1979-80. This included Vengsarkar and Gundappa Viswanath in the first innings, and Gavaskar and Kapil in the second, as he skittled India out for 160 during a riveting fourth day’s play. Unfortunately, Pakistan batsmen fell to the spin of Karsan Ghavri, Dilip Doshi and Shivlal Yadav, and lost by 131 runs. His extraordinary effort went unrewarded, once again buried from the public memory by disappointment.

He did capture 11 wickets at Karachi, including seven in the second innings, bowling Pakistan to a win against Greg Chappell’s Australians in 1980. But, it was not the same as beating India in India.

The Willis bouncer

Besides, his name was forever entwined with another epochal event which had little to do with his bowling. Sent in as a nightwatchman in the Test at Edgbaston, 1978, Qasim was batting with steely resolve for over 40 minutes on the fourth morning when Bob Willis decided to bounce him.

The first ball of Willis’s sixth over of the day sailed harmlessly, way over Qasim’s head. The fast bowler switched to round the wicket and two balls later sent down another snorter, this time searing at his head. Qasim was way short of ability to deal with it. He turned square and attempted to duck underneath it, but the ball had already struck him on the face. There was a deep gash and trickles of red flowed on to his gear. He was forced to retire, going off the field with a blood soaked towel held against his mouth. He needed a couple of stitches.

England captain Mike Brearley spoke to the press during lunch: “Although Qasim was a nightwatchman, he batted showing a good defence. We had tried everything and what do you expect?” Even after the match, Brearley remained unapologetic: “I’m sorry he was hit in the face, but he had batted for 40 minutes. In a Test match it is hard to know where to draw the line. It was one ball and if it hadn’t hit him in the face there would be no fuss.”

Willis himself denied that he had bowled to hit the Pakistan spinner and renewed his call for crash helmets to be introduced into the game so that bouncers could be bowled at anyone.

This incident was largely instrumental in removing the last semblance of resistance regarding helmets. Qasim, one of the best left-arm spinners of the post-War era, thus played a defining and painful role in the development of the modern game.

Down the years

Qasim kept on producing good performances with the ball, interspersed by one or two great ones. Some, like the 6-wicket haul against the mighty West Indies at Faisalabad in 1980 came in yet another losing cause. But there were winning efforts as well, the most satisfying perhaps the 7 wickets at Melbourne in 1981 which gave Pakistan victory by an innings. He was often sidelined with Qadir being preferred over him when the number of spinners in the side had to be limited. But, he still remained a regular in the side.

He played vital roles in back-to-back wins at Lahore and Sind in 1984 against the Kiwis, but somehow lost his place in the side after a single Test match in the return series in New Zealand. Strangely, with 137 wickets at 29.15 from 41 Tests, he was sent into wilderness for a couple of years before returning against India in that famous 1986-87 series. And seven years after he had ended up on the losing side, he finally bowled Pakistan to a win over India in India with his star-turn in Bangalore.

But for the two-year gap, and the regular preference for Qadir, Qasim could perhaps have reached the landmark of 200 Test wickets. Yet, even without that, his record remains impressive — as is amply demonstrated by the tables provided earlier. As batsman he was difficult to dislodge when he decided to dig in, but was unpredictable otherwise. He took 17 innings to reach double-figures for the first time. Yet, sent in as a night-watchman in 1982 against Sri Lanka at Karachi, he enjoyed himself by scoring his only half century in Test cricket. He averaged just 13.07, but down the years his batting kept improving, and for the last few series scored at more than 20 per innings. It was not for nothing that the astute Imran Khan sent him up the order in the second innings of the Bangalore Test. He was also a safe and often brilliant fielder close to the wicket.

The selector

Qasim served as interim selector for Pakistan from 1998. He also held several coaching positions, including serving as the head of sports in National Bank of Pakistan.

In 2007, still a national selector, he suffered a heart-attack. Thankfully, he recovered and two years later was appointed the chief selector of Pakistan. There have been interim resignations after disastrous performances by the side, but Qasim continues as the supremo of the selection committee.