Kepler Wessels, born September 14, 1957, battled his way through South African isolation, going through fascinating and curious journeys around the globe and across teams. He played as a rebel, multiple times, as an Australian cricketer and led South Africa after their readmission and was one of the gustiest batsmen around. Arunabha Sengupta looks back at one of the most fantastic cricketing journeys of modern times.

The curious rebel — Part One

VLF Park, Melbourne, 1979. Under lights. The bouncer from the fast and furious Colin Croft struck him on the back of his head. The 21-year-old staggered as the crowd let out an audible gasp. The fast-developing bump began to throb, but the boy put his head down, tucked his chin in and concentrated. Andy Roberts was cut searingly to the point boundary. It was the most competitive cricket on offer, played in front of a disappointingly sparse crowd. A super-charged Kerry PackerSuper Test between the World Series Cricket (WSC) teams of West Indies and Australia.

The youngster, fresh in the country and dripping with determination, remained defiant. His score reached 66. Croft charged in again, along his usual furious run up, stepped wide of the crease and his arm came over. The thunderbolt pitched short and cut back into the left-hander, thudding into his groin. The young man fell to the ground, his abdomen exploding in pain. Everything went black as he lay still. A doctor hustled into the ground and performed emergency resuscitation manoeuvres. The batsman groaned and stirred.

“You’d better leave the field,” the good doctor advised.

The response was a grunt, short, brusque and negative. The lad could not afford to go.

It had not been a couple of months since he had landed in this strange country. The initial few good scores for the WSC Cavaliers in the side matches had been followed by a fighting back to the wall knock. It had come in another SuperTest for the WSC Australians against an attack of Imran Khan, Mike Procter, Garth le Roux, Clive Rice and Derek Underwood of the WSC World XI. After a good 46 and a rallying stand with captain Ian Chappell he had hit one back to Underwood. The knock had pleased him, he seemed to have middled them well.

After the match, the door of the dressing room had been pried open and the imposing form of Kerry Packer himself had loomed in the doorway. Looking directly at the youthful batsman, the sponsor of the cricketers had bellowed, “We don’t import people to score 40s. Get your arse into gear.”

Hence there was no other way out. He had to grind it out. Even if he fainted on pitch. He took guard again, struggled his way to survive till the dinner break. The interval allowed him to recover. On resumption, he carried on with resolute determination. A carefully placed dab brought up his hundred.

He finally lost his stump to Croft, but by then he had 126 against his name.

After stumps, Packer looked in as usual. Skipper Chappell was ready for the big man. “So, Kerry, is that the sort of innings we expect from an import?” Seated next to his captain and hero, Kepler Wessels grinned.

It had already been a tale of unusual circumstances — a saga of guts, glory, sweat and blood for the Afrikaner youth from Bloemfontein. All the other South Africans were playing in the tournament for WSC World XI. And here he was, opening the innings for Australia.

It would continue to be a curious and fascinating journey all his life — one of the most remarkable tales of a modern sporting life.

Every step would be taken with exceptional perseverance and ambition, over seemingly insurmountable obstacles of circumstances and situation. His career would proceed as a misfit, first the sole Afrikaner among English speakers, then the sole South African among English professionals, the unusual overseas player for Australia, the supposed deserter leading the re-emerging South Africans, the straight talking and incredibly hardworking professional captain among bitter politically fragmented state sides.

He would be targeted by the press, public, players — because of his roots, his language, because of his adopted land, because of his rebel affiliations, because of his country’s policies, even because of his overwhelming zeal to succeed.

He would face the wrath of the greatest West Indian attack by being identified as a Springbok, albeit in Australian colours. He would be forced out of South Africa because of frustration, hounded out of Australia because of misunderstandings and suspicions, even snubbed by a Prime Minister.

He would have to uproot his life, pick up the pieces and rebuild from scratch — multiple times. He would play as a rebel three times in his career, in three different circumstances, for three different teams.

Yet, he would battle every blow that life had to throw at him. Every disappointment would result in harder, fanatical training regimens. He would not only work out, bat, bowl, catch and throw. He would box too. He would answer the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune by punching the bag in the most hardboiled, gimmick-free gyms in town. The blows of life would make him taciturn, reserved, sometimes offensive and querulous.

Finally , he would manage the impossible of official international cricket success during the South African isolation. And he would lead South Africa to glory after their comeback on the world stage.

The career of Wessels was incredible, one of a kind tale of a journeyman cricketer who desperately wanted to fit in. Success graced him repeatedly, before being followed by yet another of the many bitter challenges. Yet, he did succeed in the long run. He could look back at the end of his playing days with considerable pride and not a little surprise. Not many can walk the treacherous tracks that he ended up covering and stay standing.

Cricket before courtship

Wessels was born on September 14, 1957, in a middle-class household in Bloemfontein. According to family traditions, as the second son he was supposed to take the name Petrus Christoffel from his maternal grandfather. However, the old man had a request for father Tewie and mother Marguerite. He had lost a son of huge sporting and musical talent at the age of 11 — to the cruel hand of pneumonia. He had also been born on September 14, and was called Kepler. Could they name the child after him? The parents said yes.

Cricket was taken up early. At the age of six, young Kepler Wessels sat in the window adjacent to their drive. He saw the approach of Johan Volsteedt, the son of AK Volsteedt, the headmaster of Grey College. The young man was there on a date with Marietta, the elder sister of Wessels. Young Kepler knew vaguely about the sporting prowess of the young man but was not aware of the details.

As the suitor approached nervously in his well pressed formal shirt and tie, the kid piped up, “What sport do you play?” Informed that it was cricket, he coaxed Volsteed into the garden, and there followed the first informal lesson on the game. This became the pattern of every Sunday. Instead of awkward and nervous conversations with the attractive Marietta, Volsteedt spent the afternoons bowling at young Kepler Wessels. At first Marietta fumed, later she fielded.

Kepler Wessels is the only batsman to score centuries for two countries and the only player to score 1,000 runs for two countries © Getty Images

Swimming, tennis and cricket

Wessels did not restrict his involvement to cricket. Older brother Wessel Wessels played rugby for Grey College. Kepler followed and watched from the stands, dressed in the same jersey as his brother. Father Tewie, himself a versatile rugby player and later a famed referee, took his sons to watch rugby at the Free State stadium, occasionally Test matches at Ellis Park and Loftus Versfeld. Joggie Jansen, the crash-tackling Free State centre who would later play for the Springboks, had been the babysitter for Wessels.

Wessels joined the rugby team at Grey and played fullback for the Free State primary schools team. He enjoyed himself immensely, and could recall the results of these matches years later.

His mother would take him swimming early in the morning, and he could lap the 50 metre pool 20 times. Before long Wessels set Free State junior records in backstroke and breaststroke.

Additionally there was tennis. Wessels was incredibly talented in this sport, and soon it would be a difficult choice between cricket and tennis would be a major decision.

Cricket entered the frame seriously in 1966 when his kidneys became dangerously inflamed. Swimming was taken out of the equation as he recovered fromnephritis. The kid’s father wondered about a new sport to channelise the boy’s extraordinary energy. Tewie Wessels approached the master in charge of cricket at Grey College, to find his son some role even though he was too young. It was a delight for the captain of the school team – that very same Johan Volsteedt who had taught him the basics some years ago, at the cost of an unfulfilled courtship.

Soon, Volsteedt’s telephone would ring at seven in the morning in the winter — the young lad wanted some balls thrown at him. The routine followed even when Volsteedt left the school and returned as a teacher. He always obliged.

The first century was scored at the age of nine and he was pitchforked into the Free State Under-13 side. By the end of the 1969 season, he averaged 260 for Grey.

However, there was a major decision to make. In tennis, as a boy he was coached by San Marie Cronje, mother of Hansie. Later, the training was imparted by the likes of Jacke du Toit. He had a strong serve, a solid volley and an excellent double-handed backhand. Above all he was obsessed about winning. A loss would result in tears and brooding silence. He worked harder than every other boy as well as some of the professional sportsmen. His tennis drills started at four in the morning.

During his early teenage, Wessels travelled the country, taking part in tennis tournaments of his age category. Glowing reviews appeared in the newspapers. By 1973, he was the No 1 ranked under-16 player in the country. Wessels was offered a scholarship from Houston University in the United States amounting to $25,000 over four years — an incredibly large amount for an Afrikaner boy from Bloemfontein.

His main rival during his tennis days, Johan Kriek, bagged a similar scholarship to travel to USA, and went on to win two Australian Open titles. Wessels opted for cricket.

The Schoolboy Cricketer

In October 1975, Wessels led the Afrikaans Grey College to a win over the English medium Queen’s College. It was the first time that Grey had triumphed over Queen’s since 1957. The captain during the previous triumph had been Ewie Cronje, father of Hansie. Wessels scored an unbeaten 130 out of 227. AK Volsteedt, Johan’s father and the former headmaster, remarked that it was the finest schoolboy innings he had ever seen.

Selected for the school first team at the age of 14, Wessels soon broke into the Nuffeld Week festivals, was selected for the South African Schools in 1973 and 1975 and was the captain in 1976. His teammates for SA Schools included a hard hitting youngster called Allan Lamb. The 12th man was a boy from Cape Town named Peter Kirsten.

It was during his unexpected omission from the South African Schools team in 1974 that Wessels showed the first signs of the intensity with which he took these disappointments. Luckily, as he was trying to get his strokes past his moroseness, he was spotted at the Grey nets by Colin Bland, the captain of Free State. The legendary fielder was impressed by the tenacity and the application. The seriousness with which Wessels took the nets sessions would soon become a legend.

In January 1974, Wessels was ushered into the tough world of First Class cricket on Bland’s recommendation. On his debut, he walked in at No 9 and scored 32 against North Transvaal. By the next season he headed the province’s batting averages.

When he left Grey College and joined University of Stellenbosch he did so in order to have better cricketing prospects for Western Province under the dynamic leadership of Eddie Barlow.

The results were good. He impressed Ian Chappell with an unbeaten 88, scored out of a total of 182 against the International Wanderers team that included Dennis Lillee, Gary Gilmour, Ashley Mallett, Underwood and Phil Edmonds.

But more important was the psychological boost he received from Barlow. When depressed after a run of poor scores, he was approached by his captain with the words, “You’re never going to beat this game. You never will. If you go out to bat ten times and crack it six times, you will be among the top batsmen, but you will still have failed four times. Failure is a part of batting.”

The Sussex connection to Packer

The summers that followed were spent playing for Sussex with prolific results, but there were mounting problems. At home, he felt he was being ignored by the likes of Mike Procter because he was an Afrikaner. Cricket was still essentially a game for the English speaking. Whether the snubs and the issues were real or perceived remains unclear, but Wessels had genuine problems in adjusting. The youngster was a teetotaller as well, and that did not help his attempts to gel with the rest of the team.

At Sussex, he did not quite get close to the captain Tony Greig — a South African with English speaking roots and a Queen’s College man himself. However, when he hammered 138 not out against Kent at Tunbridge Wells in a team total of 240, Wessels could see Greig applauding. It was to be one of the most important innings of his career. Within a few days, Greig had casually asked him whether he might consider joining the Packer brigade.

The answer was an instant yes. He wanted to play cricket, and it was proving difficult in isolated South Africa. However, there was one problem. He had to fulfil one year of national service in the South African defence forces from July 1977 to June 1978. So he could join the second edition. Greig agreed.

During the army training Wessels tore a cartilage in his knee while playing squash. The injury rendered him unsuitable for strenuous exercise during his period of service, but he was not too unhappy to take on the responsibility of preparing the cricket pitches. During a break from the Army, he scored 146 against Western Province B.

An apprehensive Wessels arrived in Sydney for the World Series Cup, and was met by Greig himself. Soon, the WSC organisers took over. He was put up in a hotel with a stipulation to find a job and residence soon. Besides, he would be eased into the process of World Series — by proving himself in a couple of matches for the Waverley Club.

The situation looked bleak for the young man. His life and livelihood seemed uncertain. In a strange country, he felt alone and helpless.

Help, however, was at hand — from Peter Mackenzie, a Waverley cricketer. A room was found for him to sleep. A job was found — pushing supermarket trolleys laden with legal papers for A$120 per week.

Wessels was relieved. In his third match for Waverley, he scored 123 against Penrith, and soon followed it up with 137 against the Sydney Club. The New South Wales selectors named him in the state training squad. And at this juncture Packer called.

A rebel for Australia!

It had been Greig’s idea to play Wessels in the World XI — a team that included several South Africans in the form of Procter, Rice and le Roux. However, Packer had other ideas. To generate public interest in this parallel circuit, Australia had to do well, and they needed a good solid opening combination. Wessels could be one half of it. The boss prevailed. Wessels started playing for the Australian team. His contract was set in motion. The days of pushing trolleys came to an end.

Ian Chappell won his heart. He introduced the new recruit to the team saying, “Wessels is coming to play with us. If you don’t like it, score more runs than him.”

It was a fascinating experience. Andy Roberts hit him in the ribs. Wessels, bandaged around the chest, scored 48. When Javed Miandad unleashed a volley of abuse at him from short leg, and was joined by bowlers of World XI, Ian Chappell came up from the non-striker’s end and mouthed expletives that took the verbal war away from the youngster and turned the focus on the captain.

Chappell instructed Wessels to stick around in One Day cricket and build a platform for the team. Wessels nodded and scored 136 not out in the first final, out of a total of 208. That would be his style in limited overs through his career.

Lillee, Rod Marsh and Greg Chappell nodded approval, and Wessels could at last be seen sipping beer after a day’s play. He emerged from the 1978-79 season as the leading scorer in all matches. His SuperTest average was 41.57 — splendid given the incredible bowling one had to negotiate.

However, he could not participate in the West Indies leg of the carnival. His South African passport did not allow him to travel to the Caribbean. Yet, there were more delightful rewards to be reaped from other quarters.

Working in the public relations department of the World Series Cricket organisation, was a Sydney girl named Sally Denning. They met in a promotional function and hit it off immediately. The intense Wessels relaxed while she was there, as the two talked for aeons seated in the cricketer’s car.

He flew back to South Africa after the Australian leg of the WSC. At home, he met criticism. Rice, Procter and le Roux were lauded for setting the limited world stage on fire. However, Wessels was seen as a defector. That year’s South African Cricket Annual did not contain his name.

With this negative force around him, the 21-year-old made his decision. He called World Series Cricket offices, and asked for Sally Denning. When she came on line, he asked her to marry him. The mercenary cricketer was tied in wedlock at St Wilfred’s Church, Bognor Regis, Sussex. Dawie de Villiers, the former Springbok scrumhalf and South African ambassador to London, provided the Afrikaans blessing. Jerry Groome, former Sussex cricketer, acted as the best man.

County problems

However, the happy couple soon had other problems to deal with. Sussex had started this curious policy of recruiting three overseas professionals while they were allowed to play two in the matches. One of Imran Khan, Javed Miandad and Kepler Wessels had to sit out in every match. In the end Imran played every fixture, Miandad the limited overs matches and Wessels the four day games. Frustrations grew, relationships soured. Imran and Wessels almost came to blows on the field. Wessels scored 1,619 runs in 1979 at 55.82. However, he was not enjoying it.

At the end of the 1979 season, Miandad left for Glamorgan. But, Sussex signed le Roux almost immediately. Things were not helped in 1980 when Wayne Daniel struck Wessels on the hand and the resulting fracture led a Sussex official to say, “This solves our selection problems for a while.” The South African bounced back to score 197 not out by the end of the second day in the fixture against Nottinghamshire after the opponents had been bowled out for 155, and was infuriated to find out on the third morning that the innings had been declared. His complaints over these issues were seen as churlish, moody, hard-headed and negative.

Soon the decision was taken to play two seamers for all the matches. Le Roux and Imran would play and hence Wessels was dispensable. After Wessels had amassed 254 against Middlesex, he was informed his contract would not be renewed for the next season. The batsman was actually relieved.

Brisbane bound

Further problems had been afoot since the last year. Wessels had banked on playing another series of WSC in Australia in 1979-80. But Kerry Packer had since signed a truce with the official cricketing establishment and had acquired rights to telecast Tests and ODIs. WSC had been disbanded.

Wessels had been left wondering about his future. He had written to Marsh in Western Australia, Ian Chappell in South Australia and Greg Chappell in Queensland. A contract was drafted by Queensland and Wessels was delighted. However, Packer, who still had Wessels on contract, insisted he play for New South Wales. Heated telephone conversations followed. Tony Greig mediated.

At the cost of a hefty personal financial loss, Wessels stuck to his guns. He landed in Brisbane and strode into The Gabba. He scored 56 on his debut against Victoria and ended the season heading the batting averages for Queensland. Most importantly, he had a place to return to after the acrimonious return from England in 1980.

Wessels fretted about qualifying to play for Australia. How long would it take? Would the Australian Cricket Board consider him too much of a diplomatic hot potato? He grew tense, taciturn, the remnants of the faint smile vanished from his face. He increasingly focused on training, visiting the glamourless, utilitarian Railway Institute Gym. He sparred as well, and was once roughed up in the ring by a dockyard painter who had an issue with his South African birth.

Finally, in October 1980, Allan McFarland, the government Minister of Immigration and Ethnic Affairs, officially presented Wessels his Australian citizenship. The ceremony was attended by Queensland teammate Allan Border. He would have to wait two more years to play for Australia as per the International Cricket Council (ICC) regulations. But, at least now he belonged.

At first he worked as a Public Relations Officer at Ron McConnell Holdings, where Border was one of his colleagues. Now, with the citizenship in the bag he bought The Golden Goose, the newsagents, with his in-laws. He rose every day at five o’clock in the morning to set the newspapers.

As the next season approached, Dave Richards, chief executive of the Australian Cricket Board announced that Wessels would be eligible to play for Australia in September 1982. Wessels celebrated the news by becoming the seventh batsman to score 1,000 in a Shield season.

Kepler Wessels made his Test debut for Australia against England at Brisbane in November 1982. Opening the innings, he scored 162 © Getty Images

Playing for Australia

The Australian opening pair failed in Pakistan during the 1981-82 season. The 1982-83 season was to involve the Ashes series against England. The road to the Test team seemed clear, but Wessels was taking no chances. The visitors played Queensland at the Gabba and lost by 171 runs. Wessels scored 103.

However, he was not picked for the first Test. A disappointed Wessels went back to his punishing routine, his mind filled with thoughts about diplomatic implications of choosing a South African and how it would play in the decision making of the selectors. However, John Dyson and Graeme Wood failed again in the drawn opening Test match. And ending all worries and concerns, Queensland and Australia skipper Greg Chappell drew him aside and informed, “I’m not supposed to tell you Chopper, but you are in.”

Hence, on November 26, 1982, Kepler Wessels made his Test debut at the age of 25. The noise in the media was not uniformly encouraging. Large sections of both the Australian and English media were vocal against the choice. But, Wessels was too elated to notice. He drew first blood by flinging himself to his right to catch a David Gower glance at leg-slip.

When Australia batted, Wessels opened the innings with John Dyson. Wickets fell soon. It was 11 for two when Greg Chappell joined him. At 94, the captain was run out for 53. Kim Hughes and David Hookes came and went. Australia slumped to 130 for five.

But Wessels was keen to bat on. With time, his style had become a grafter’s, the rasping cut had been transformed into a chop. Runs were scored between third man and cover point. A frustrated Ian Botham called Allan Lamb over and instructed to abuse the limpet in the crease in native Afrikaans. The all-rounder himself picked up some of the words and added his voice. It did not help.

Marsh and Bruce Yardley stayed long enough and Wessels inched towards his century. At 97 he was stranded in the middle of the pitch, trying to drive Eddie Hemmings down the ground. But, the return also beat the wicketkeeper and the batsman hastened back. The next ball was short, and Wessels pulled it past Lamb at mid-wicket. Century on debut.

The next morning he took his score to 162 before being bowled by Bob Willis. The long wait to play at the top level had proved fruitful. The amazing journey of the boy from Bloemfontein had reached a defining milestone.

From Prime Minister to Prime Minister

The runs came regularly as the Tests wore on. There were rumours of his problems with balls on the leg and middle. Wessels succumbed a few times, but worked out his technique.

He scored 386 runs at 48 in the first series. The Ashes were won. At the Hilton Head hotel in Sydney, Malcolm Fraser, the Prime Minister of Australia, hosted a cocktail party for the teams. The home team players lined up to shake hands with the dignitary. Fraser approached every cricketer, shook hands and exchanged pleasantries. When he came in front of Wessels, he glared at him and turned away. The hero of the moment had been snubbed by the Prime Minister of the country which had accepted him as citizen.

Wessels performed creditably in the tri-series that followed, following the Ian Chappell dictum of anchoring one end. However, he was faced with the criticism that would dog him all his career. He was said to be too slow. The accusations followed him to the 1983 World Cup in England. Fresh from a hundred in the only Test in Sri Lanka, he was soon dropped because of his sluggish paceduring Australia’s miserable campaign. A couple of meaty scores in defeats did not help.

When he was left out, Wessels had the immediate misgiving that captain Kim Hughes was not too keen on having him, an ex-WSC man, in the side. His pronounced sulk did not allow Hughes to come clean either. However, on return to Australia, Hughes drew him aside and said that he was very much in the scheme of things and an essential member of the side.

Much relieved, Wessels plundered 179 at Adelaide against Pakistan. He did not do to well in the remaining Tests of the series but performed creditably in the ODIs, also bowling some seamers in the process. He had been a dubious choice in the shorter format, but Hughes had stuck up for him. One of his most vocal critics had been Tony Greig for Channel Nine. At the end of the tri-series involving Australia, West Indies and Pakistan, Wessels got up on the stage to receive the Man of the Series trophy from Greig.

The ordeal by pace was the next challenge. A new-look Australia, without Chappell, Lillee and Marsh, travelled to West Indies. Wessels, after two ordinary Tests, had to return to Australia to have an operation on his troublesome knee.

A hiatus from Test cricket followed, during which Australia played a series of ODIs in India. Wessels scored 107 at the Jawaharlal Nehru Stadium and was once again the Man of the Series. Despite that critics still doubted his merit in ODIs.

The second chapter of the pace challenge now faced our man: West Indies visited with their usual battery of fire breathing fast men. Hughes, pummelled and defeated, bid a tearful adieu to captaincy. Joel Garner got Wessels repeatedly with deliveries slanting across him. Newspapers were quick to write off the South African import. “Goodbye Kepler, Big Bird’s Bunny Again,” screamed the headlines after his dismissal in the first innings of the second Test at The Gabba. And Wessels countered this with a makeover from grafter to stroke maker. In the second innings, he struck the ball hard and frequently to score 61. In the following Test at Adelaide he got 98 and 70. Another 90 followed at Melbourne.

Finally the last Test was played at Sydney. Wessels batted through the first day to score 120 not out. That evening, the new Prime Minister Bob Hawke visited the dressing room. This time the head of state congratulated him. The wheel had turned its little circle in the diplomatic spheres.

The next morning he was bowled by Holding for 173. Australia, having lost the series, won the final Test by an innings. Wessels had scored 505 runs in the Tests at 56.11.

Accusations and Anger

However, problems continued. He was floated up and down the order in ODIs and it affected his consistency. He was troubled by his knee. Soon, all his niggling doubts revisited him. He stood brooding in the nets, when Hughes approached him with harmless banter. Wessels did not like it. The result was an ugly wrestling match. When they were separated, neither of them held a grudge. Yet, it underlined the constant pressure that plagued Wessels all his career.

And now things turned to worse. Ali Bacher and his men were busy recruiting Australian cricketers for a planned rebel tour of 1985-86. Wessels was approached by Bacher as well as by members of the Australian team. Bacher wanted to know about the Australians. The teammates wanted to know about South Africa. He never signed a contract, but was persuaded to sign a Power of Attorney document giving a Brisbane Lawyer the legal right to sign for him — only if Wessels decided to go on the tour.

Wessels himself made it clear to both Bacher and the Australian Board that he had no intention to desert Australia. He wanted to play Test cricket. He was enjoying it. However, when the news of players signing for the rebel tour became public, Wessels was singled out as the possible lynchpin. He enjoyed moderate success in England — sub-par by his standards, but with only captain Border scoring more runs than him.

However, rumours were surfacing every minute. Relationship with the new skipper became strained. Phone calls were long and tedious between Wessels in the English hotels and the Australian board officials back home. Wessels sulked. He erupted on occasions. When Border was late for a meeting at Waldorf Astoria, Wessels gave him an angry mouthful.

He returned to Australia and played one Test against New Zealand. Wessels was the only one to combat the swing and seam of Hadlee with any assurance and made a steady 70. After the Test he was asked to sign a new contract with the Board, without which he would not be considered for the second Test. It was farcical. Wessels had shared the highest tier of the three-tiered structure with Border and Geoff Lawson, earning A$ 35,000 per year. The new contract was to place him in the bottom tier at A$ 12,000.

It was a crude signal for him to leave. Wessels refused to sign and walked out. That was the end of his 24-Test career for Australia. He had scored 1,750 runs at 43.00. During this four year period, no one but Border had a better record in the team.

In the Sheffield Shield final of the season, Wessels led Queensland in the absence of Border and hit 166. New South Wales survived to hold on for a draw by the skin of their teeth. There was thus no happy ending to the Australian summers for Wessels. During the post-match ceremony, he took the microphone and voiced, “I want to thank the ACB for forcing me out of the Test side and giving me the opportunity to play with the best guys I’ve ever met.”

In hindsight, such a comment was perhaps unnecessary. But, Wessels was beyond caring, He was leaving for South Africa.

The curious rebel — Part Two

He went back and once again assumed the role of a curious rebel. He had travelled from his homeland South Africa and had played in the Packer series as an Australian batsman. Now, as he landed in his native South Africa, Ali Bacher coaxed him to join the Australian rebels.

The South Africans were deemed too strong for the visiting side. Wessels was a much needed boost to make the matches competitive and attractive for the spectators.

It was bizarre. The Australian team was not really welcoming, but the captain was. Kim Hughes welcomed his old crony with warmth and alacrity.

Wessels did not start well, but ended with three consecutive centuries, two in the same match at Port Elizabeth. The final hundred, an exquisite 122 off 112 balls in Port Elizabeth, was sheer brilliance. That day Wessels shed his armour of stodgy defence and gave full vent to his strokes. Sadly, such days were few in his career.

Eastern Province revolution

The rebel tour was his final shot as a hired gun for Australia. Soon Wessels turned his attention to Eastern Province. The revolution that he achieved for the provincial side stands shoulder to shoulder with every glittering achievement of his career.

Handed the captaincy, he hatched out a three-year plan. The province had not won anything in the past 97 years. Wessels produced a roadmap. Compete the first year. Win a One Day tournament the second year. Win the Currie Cup the third year.

And he achieved all three.

Turning to his extreme physical training drills, he took the amateurish side through a regimen which soon saw them grow fitter than the rugby units. New players like Dave Callaghan were discovered. Formidable ones like the Australian rebel bowler Rod McCurdy were recruited. Greg Thomas of England was another major name. Slackers were discarded.

In 1986-87, the side competed and competed well.

In February 1988, Wessels lifted the Nissan Shielf. “Hierdie is ‘n grootoomblikvir my, en vir die Oostelike Provinsie,” he said in Afrikaans. “This is a great moment for me and for Eastern Province.” Never before had there been an Afrikaans victory speech in South African cricket.

In March 1989, Transvaal captain Clive Rice’s last resistance finally came to an end when Thomas got him caught at short leg. Within a few minutes Eastern Province had won the Currie Cup final.

All the milestones had been achieved.

The next year, Eastern Province won the Shield, the Currie Cup and the Benson Hedges night series.

Wessels had transformed the side.

Somehow all this led to movements to replace him as captain. Players like McCurdy rebelled against his military approach to cricket. However, intervention from Geoff Dakin, the South African Cricket Union President, ensured that this rebellion was quelled.

The curious rebel — Part Three

At the same time, more trouble was brewing. Under Mike Gatting, England had travelled for another rebel tour in chaotic political conditions. And several home cricketers questioned the right of Wessels to turn out for South Africa within the few years of his return. Controversies raged. On the cricket ground Wessels had open feud with Jimmy Cook, one of the major voices against his inclusion. In the Nissan Cup final he gave Cook a public send off after the batsman was dismissed. Meanwhile Gatting’s men had to wade through huge political protest gatherings to get to their matches.

Wessels played the first ‘Test’ and failed with the bat. After the game, he overheard Cook the captain in conversation with a senior player, wondering about getting Rice in the team by dropping Wessels. The opening batsman walked out of the Springbok side. The same day, Nelson Mandela walked free from prison after 27 years.

The dawn of a new era

And suddenly all the darkness vanished and light of a new era beamed brightly on South African cricket. ICC welcomed the nation back in the cricketing fold. In November 1991, UCB representatives visited Calcutta to discuss plans for a South African visit in late 1992. Jagmohan Dalmiya welcomed a team the very next week.

On November 7, 1991, a South African side travelled to India on a historic tour of three ODIs. Led by Clive Rice, the team included Cook, Kirsten, Adrian Kuiper, Brian McMillan, Allan Donald… and a smiling Kepler Wessels.

The welcome was unbelievable. Thousands emerged on the streets to welcome the side. The ride to the hotel from the airport should have taken less than half an hour. It took six times as long.

Wessels played one down, and scored 50 in the first match at the Eden — won by India riding a heroic Sachin Tendulkar innings in the face of Donald’s thunderbolts. He followed it up with 71 at Gwalior in another defeat, and then a breathtaking 90 in a superb win at Delhi. Thus the man criticised as a limited overs batsman won yet another Man of the Series award.

Returning to South Africa, the preparations for the 1992 World Cup started in full swing. And so did the various undercurrents of Board politics. During the Eastern Province-Transvaal Currie Cup match, Rice walked in to bat at the fall of the fourth Transvaal wicket. On his way to the crease, he turned to the Eastern Province skipper Wessels. His words? “Good luck in Australia. I’m not going. You’re the captain.”

Life had come a full circle for Wessels. The undercurrents which led to Rice’s ouster can be despised, but for the mercenary cricketer of the 1980s, it resulted in the greatest honour. The preparations began in full earnest. Mike Procter was the coach.

Leading the World Cup campaign

The young inexperienced side began the campaign at Sydney against hosts Australia. They were buoyed by a message of goodwill from Mandela. A charged up youthful bowling attack restricted Australia to 170 for nine. Wessels opened the innings and took the game by the scruff of the neck. Bruce Reid bounced and he rocked back to pull. The ball soared, white against the black nightsky. The scoreboard announced, “Kepler Wessels 2000 runs in One Day Internationals.” A wag from the Hill voiced, “Yeah, 1950 of them were for us.”

South Africa won by nine wickets. Wessels remained unbeaten on 81. Border offered his congratulations. In the dressing room Steve Tshwete, African National Congress (ANC) veteran and spokesman on sport, held him in tearful embrace. After a few minutes Wessels was talking to an effusive FW de Klerk on the phone.

The green brigade galloped through the tournament as dark horses, and the young bowlers delivered. Battle-scarred Peter Kirsten, a last minute inclusion, revelled in the challenge with the bat. Wessels guided the side with a firm hand from the top of the order and in the field. In the final group match they needed to win against India. Wessels came down the order in the 30 over game, sending Kirsten and Andrew Hudson to open the innings. The move paid off. The match was won with the captain unbeaten at the wicket. South Africa were through to the semi-finals.

The progress in the tournament was not without its own trials and tribulations though. After the win against Australia, the fax number of the South African team had been publicly shared for people back home to send through congratulatory messages. After the team lost the next match to New Zealand, the same number had been used by many to hurl abuses on the team and particularly Wessels, the Afrikaner captain.

Besides, four days before the semifinal, there was the referendum called by President de Klerk back home. The white and non-white voters were given the simple choice of Yes or No to reform. As Dakin, the UCB president, told the journalists, “If it is No, it will be impossible for us to continue in the tournament.”

In his Sunday Times column Wessels urged the people to vote Yes for a fair and prosperous future. But, the prediction was for a slim majority of 55% to 45%. The cricketers kept their fingers crossed.

Finally the votes amounted to a resounding 68% in favour of Yes. The issue was obviously far more important, but there was definitely just a tiny proportion who had voted because they wanted to see South Africa play England in the semi-final.

And then, in a tragic end to their journey, they were done in by an imbecilic rain rule. With lights flooding the ground and after a short shower which did not bother them again after ten minutes, the organisers suffered collective brain freeze. With Brian MacMillan and Dave Richardson at the crease, the Proteans had required 22 off 13 balls for a win. After the interruption, with the world waiting with bated breath, the target was readjusted to 22 off one ball. The South Africans ended the competition with a lap of honour, cheered by the thousands in Sydney, and but for the ridiculous rain rule it might well have been the victory lap. Wessels had conquered the Australian hearts, this time as a South African.

The reception back home was unprecedented. Jan Smuts airport overflowed with people and the next day 40,000 lined the streets of Johannesburg as the squad was paraded to a reception outside the City Hall.

At the helm

This was followed by another tour arranged on extremely short notice — another historic one. The team, virtually unchanged from the World Cup, travelled to West Indies for one Test and three ODIs.

At Kensington Oval, Wessels became the thirteenth cricketer to represent two countries in Test cricket. By the third day, West Indies were just 103 ahead in the second innings, seven wickets down. The young South African side had the mighty team on the ropes. However, the hosts recovered to set a target of 201. Wessels, in the wake of a magnificent 59 in the first innings, scored 74 in the second, sticking to his strategy of taking the attack to the fast bowlers that he had adapted against West Indies while playing for Australia. South Africa ended the fourth day at 122 for two, victory all but within their grasp.

But, the following morning, he departed at 123. The visitors slumped to 148 all out in front of Curtly Ambrose and Courtney Walsh.

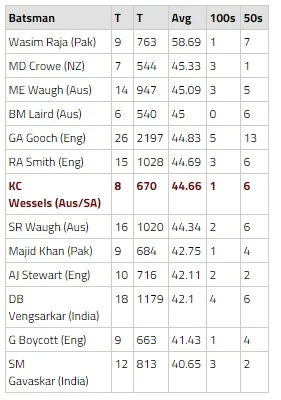

With this performance, Wessels ended his memorable duels with West Indian fast bowlers. During the peak period of Caribbean pace, Wessels was at the top of the pile of batsmen who performed creditably against them.

* – The period considered for analysis is April 21, 1976 to April 29, 1995 apart from eleven Tests played by a depleted side between March 3, 1978 and February 2, 1979.

On return, the South Africans met the visiting Indian side led by Mohammad Azharuddin. Baking on a wealth of fast bowlers in the form of Donald, Brett Schultz, McMillan and Craig Matthews, South Africa won the Test series 1-0 and the ODIs 5-2. Wessels led from the front, 295 runs at 42.14 in the Tests and 342 at 48.85 in the ODIs. This included 118 at Johannesburg in South Africa’s first home Test in two decades, becoming the first man to score Test hundreds for two countries. He still remains the only one to the feat.

However, he was still criticised, severely. His approach was said to be too defensive. He was accused of letting Indians off the hook in the second Test, not attacking enough. The 1-0 Test outcome did not satisfy many. South Africa should have won by a larger margin, they argued. It was ignored that after a 22 year hiatus, it is not easy for a side to go into the international fold and start winning. According to Wessels, the people at home were still living in their 4-0 rout of the Australians in 1970.

Kepler Wessels (right) tosses the coin as South Africa host an international team for the first time since their excommunication © Getty Images

The bigger furore was raised over the clash with the great Kapil Dev. At St George’s Park, the Indian all-rounder ran Kirsten out after the batsman had backed up too far before the ball was delivered. Kapil had warned him often enough, and was perfectly justified in taking off the bails. Kirsten was obviously not amused. Batting at the other end, neither was Wessels.

When, soon after the incident, Wessels turned for a second run and his bat slammed into Kapil’s shin, the Indian winced and many eyebrows were raised. The South African captain was universally condemned. Severely. There was not enough proof that it was deliberate. Kapil said he could not be sure. Wessels was not confessing. Clive Lloyd, the match referee, could not pronounce a more severe verdict than a warning. But, this manoeuvre of ramming the bat in the bowler’s shin was common enough in Currie Cup. Wessels did not win any popularity contest with this misdemeanour.

Yet, with this series, the captain had settled down. The team was improving by leaps and bounds. The goal was to become the best in the world in a few years, and Wessels went a long way towards achieving it.

A tour to Sri Lanka was victorious. The Proteans reached the semi-final of the Hero Cup, for all intents and purposes a mini-World Cup, and were ousted by a freak final over by Sachin Tendulkar.

A trip to Australia followed, and Wessels played the first two Tests with a severely damaged knee and batted for over an hour in the second Test at Sydney with a broken finger. He could not field in the second innings at Sydney. But he masterminded Border’s dismissal and watched from the stands as Donald and Fanie de Villiers ended the Australian innings at 111 as they chased 117. Young Cronje took over for the third Test as Wessels flew back.The match was lost, but South Africa had roared back into international cricket by holding Australia 1-1 in their backyard.

A similarly keenly contested return series followed in South Africa, the old friends and rivals Border and Wessels slugging it out for the last time. It ended in another 1-1 verdict. The 36-year-old Wessels was no longer getting the runs regularly, but the side was fast becoming a major force in world cricket.

Wessels played his final series in England in the summer of 1994. At Lord’s, he was his usual impeccable no-frills self, grinding out a hundred in five hours. South Africa won the first Test between the two countries in 29 years — by a huge margin of 356 runs. Wessels was the Man of the Match.

A collapse in the second innings at The Oval saw the hosts squaring the series with a eight wicket victory. Wessels ended his career with another drawn series. The reins of the side were handed over to the now fully prepared Cronje.

In retrospect

Thus ended a career of relentless struggle with circumstances and fate that would have constrained any lesser man. Some would have given up at the first cruel blow of chance, others at the hundredth. Wessels just refused to buckle and in the end played as many as 40 Test matches, 24 for Australia, 16 for South Africa. His career numbers tailed off towards the end but stand at a respectable 2,788 runs at 41.00 with six hundreds. In 109 ODIs he amassed 3,367 runs at 34.35 with a solitary hundred and 26 fifties. In the early to mid-80s, he had definitely been one of the major batsmen of the world.

In a mercenary career which saw him play for seven different First-Class sides across South Africa, Australia and England, and Tests for two countries, he turned out in 316 matches and scored just under 25,000 runs with 66 hundreds. The most remarkable was perhaps his 94 matches with 8,027 runs at 59.02 for Eastern Province, a side that he turned around from an amateurish outfit to a team of world beaters.

Later he returned to the county circuit and coached Northamptonshire until 2006. Son Riki Wessels, born as he was returning from Australia in the heated days of late 1985, played for Northamptonshire and is currently representing Nottinghamshire as a wicketkeeper batsman.

In 2008, Wessels was invited to coach the Chennai Super Kings in the Indian Premier League.

Lacked style, but he was The Man

Never a pretty batsman to watch, Wessels often dismayed the cricket romantics with his ugly stance and his obstinate, adhesive batting style. The shoulders were stooped, the toes twitched, the back-lift was short and the bat prodded around the front pad. But, every movement of his continuously evolving technique was backed by loads of guts.

There were many who felt Wessels could have been a free-flowing batsman as in WSC 1978-79. With time he overcomplicated his style. The lofted drive was taken out of his repertoire, the head high hook became less frequent, the whirling of the bat outside the off stump, which had characterised his initial forays to the wicket, was soon shelved. Discipline took over and the chop like square cut was used over and over again.

But the attractiveness was sacrificed to gain huge ground in efficiency and risk free limpet-like qualities. He perhaps lacked the class of Allan Border, but had all the qualities of his attitude and approach. He was never a Pollock or a Gower, but grew into a solid batsman, reliable and prolific enough to become a regular in the Australian team as a South African recruit, and then in the South African team as a mercenary who had gone to play for Australia. No one questioned his ability and the runs that he put on the board.

People had reservations about his captaincy. Too much of a disciplinarian, too tough on the fitness drills, sucked out the fun from the game, too defensive when ahead in the series and so on. But, once again, neither Queensland, nor Eastern Province, nor the readmitted South Africa ever questioned the results he obtained.

During his last years as a cricketer in South Africa, Wessels worked as public relations officer in the University of Port Elizabeth and was an icon for the institute. Apart from that, he promoted the sport he loved perhaps as a physical manifestation of his character and life — boxing. He became a familiar figure in New Brighton, spotting boxing talent and backing them to the hilt. In 1991, he even took part in an exhibition bout against old Pretoria teammate Anton Ferreira as part of Dave Richardson’s benefit box-and-dine function.

And throughout his career he was obsessed with training and fitness. It was his way of staying sane in the face of continuous challenges and multiple disappointments. He drove himself to murderous extents that resulted in withdrawal symptoms when he failed to turn up in the gym for one afternoon. His knee, damaged during the squash accident of his army training days, fell prey to overtraining. Five operations were needed during the course of his career, but nothing could keep him away from the track, the treadmill.

Perhaps he had to keep running, physically and metaphorically. In the curious circumstances of birth and politics, he managed to eke out a fascinating career through relentless spunk, stamina and steadfastness. He succeeded. Given his situation, few people could have.