Omar Henry, born on January 23, 1952, became the first non-white cricketer to represent South Africa in a Test match. Arunabha Sengupta looks back at the life of this pioneering left-arm spinner who broke into the South African team even during the apartheid days.

The breakthrough

There was Kepler Wessels, still bound to his Australian allegiance, adding substance and curious political balance to the line-up. There was a useful pace attack consisting of Rodney Hogg, Carl Rackemann and Terry Alderman. Then there was class in the middle-order in the form of Graham Yallop and captain, Kim Hughes.

The rebel Australian team that visited South Africa in late 1986 was perhaps not as strong as the West Indian sides that had toured in the previous seasons, but they were more than a decent side. The cricket starved South African players jumped into the fray with gusto, and the hungry crowd lapped it up voraciously.

South Africa won the first ‘Test’ at Johannesburg, and drew the second at Cape Town. Left-arm spinner Alan Kourie struggled through the two matches, capturing just one wicket. In the second ‘Test’ he ended with none for 87 after sending down 39 overs.

The third ‘Test’ in Kingsmead had an explosive surprise waiting for the entire nation. Kourie had been visibly less than penetrative, suffering a recurrence of long-standing weight problems. In an expected move, the left-armer was dropped. The identity of his replacement hit the country’s cricketing circles like a bolt from the blue. Omar Henry, the 34-year old cape-coloured left-arm spinner from Boland was named in the eleven. For the first time, a non-white cricketer was considered good enough to play for South Africa.

Epochal though his inclusion was in the history of South African cricket, it did not meet with anything like universal approval. Outstanding slow bowlers were always a rarity in the Currie Cup. Among the few tweakers, Henry had enjoyed a fine career for Western Province and the Northern summers spent in Scotland. But, he was almost 35 and there were voices which hinted the selection as an elaborate eyewash, the rise of an unwanted quota system.

Chairman of selectors Peter van der Merwe was aware of the undercurrents and emphatically stated that it was selection on merit. “In his most recent First-Class outing, Omar scored a hundred and took seven wickets. He’s a genuine spinner and a good batsman.”

Indeed, against Natal B, Henry made 114 and captured three for 17 and four for 73. The previous season had seen him take 45 wickets at 17.97. But not everyone agreed with Van der Merwe.

The loudest voice of dissent was that of Kourie himself. He was quoted in Business Day,vehemently denouncing the selection of a B section player at his expense, insisting that he could not understand the decision.

With the winds of change in the offing, it was unwise of Kourie to voice his statements the way he did. His poor form did not help matters. Once a regular in the South African sides, he was now pulled up for his indiscretion. Within a week he had been fined 2000 Rand and had been forced to issue an abject apology. Van der Merwe coldly observed, “I’m not prepared to give details of why the selection panel dropped Kourie, save to say that in our opinion he did not measure up to what we expected of him. In fact, some players can be grateful that we don’t say why they have been dropped.”

But even in the non-white community, there was a strong feeling that Henry was not quite the best cricketer among them. In fact, he had also been branded a traitor, even a ‘Nazi’ when he had left the South African Cricket Board of Control (SACBOC) set up by the activist Hassan Howa – the body which governed the game for the non-whites in the country. His crossing over to the South African Cricket Union (SACU) had not been accepted by his people. According to the non-white leaders, there were better ‘coloured’ cricketers, with a stronger claim to play for the South African side, who had stayed loyal to the wider cause.

There was some justification in the cause of the boycott. The rebel tours were seen as part of a wider strategy to buy more time for apartheid. The presence of a coloured cricketer in the same international team, at a time when he could not go on the same beach as his team-mates, was seen as a propaganda coup. However, the reactions were rather extreme. Henry’s elevation to the national side resulted in death threats. Armed guards had to be stationed outside his family home.

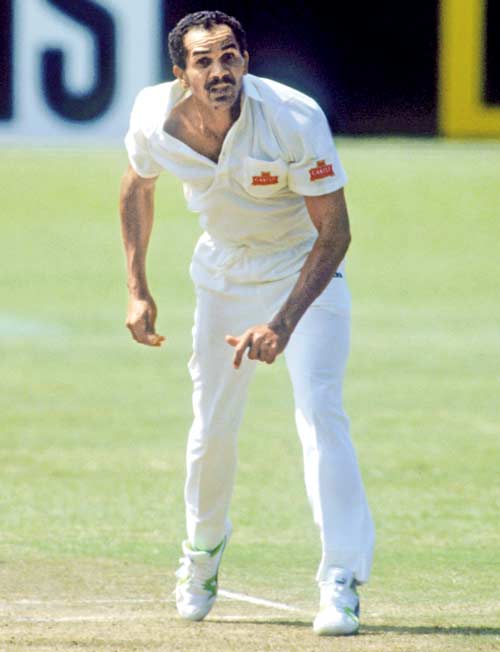

Omar Henry took 443 wickets in 131 games at 25.17 in First-Class cricket © Getty Images

A cherished triumph

For Henry himself, though, it was a triumph of perseverance. “I did not expect it,” he told reporters. “It has come as a big surprise. I feel it is just reward for many years of hard work I’ve put into the game and I only hope I’ll be worthy of the national selectors’ faith in me and not let South Africa down.”

He did not let them down. His performances were not exceptional, but with Garth le Roux attacking from one side with short spells of furious pace, Henry played his part in choking up the other end almost to perfection.

It had been a long journey for the spinner, much of it through an unending tunnel ending with sudden release into unexpected and unaccustomed brightness.

Born in Stellenbosch in the Cape Province, Henry grew up sharing one room along with six siblings and his parents. However, in spite of the cramped confines of his formative years, he did herald from a sporting family. His maternal uncles and grandfather were good rugby players and useful cricketers. His father was a rugby player of some merit as well. The uncle on his father’s side died at the tender age of 21, and Henry never met him. But, he used to bowl left-arm spin.

He grew up watching the matches involving the non-whites and idolising Basil D’Oliveira. He met his hero when he came down to coach at his school.

Playing in the SACBOC circuit was the best that non-whites of the late sixties and early seventies could aspire to, but Henry earned a break in the most convoluted way. A game he was playing at Durban for a non-white side was washed off. On the way back to the hotel, he passed Kingsmead where Natal was in action. Henry sneaked in and watched the game, thus incurring the wrath of Hassan Howa. He was charged with patronising the ‘racialist’ cricket, but the young man refused to apologise. Henry was banned from SACBOC games and received his first death threat. Resolutely, he stuck to his guns.

He found favour on the other side of the Apartheid wall, and started playing under SACU. He continued to bowl, picking up the secrets of the art from Lefty Adams and Owen Williams. When he went to England in 1977 to play in the Lancashire league, he had the privilege of watching Bishan Bedi and Derek Underwood from close quarters.

By 1978, he had become a permanent fixture in the First-Class scene, first for Western Province, then Boland and finally Orange Free State. Relying more on flight than spin, he turned out to be a successful bowler. When required, he could give the ball a whack from down the order as well. With time and performance, the doubts surrounding quotas were silenced and it was obvious he was in the Currie Cup solely on merit.

Seated in the uncovered stands for the non-white spectators, he had watched Barry Richards, Graeme Pollock, and the others play in the Newlands Test of 1970. Like thousands of his people, he loved the game. However, playing for the nation was a distant dream for the coloured populace. Henry knew he did not lack ability. Indeed, he also knew that some others – the Magiet brothers, Saayit and Rushdi, Sidick Conrad – who were even more talented. The difficulty lay in the mindset – the lack of belief that it could be done. His people discouraged him thoroughly, believing that he had sold himself out. But, there was a small ray of hope that increased with each passing year. Change was definitely in the air. But, at the same time, he was approaching his mid-thirties.

And now, suddenly, he had made it to the ‘Test’ side. It was a remarkable high in his career, something that he had fantasised about – maintaining in the realms of dreams, never quite gathering the courage to believe. He knew circumstances had played a role, and he was fortunate to have become the first coloured cricketer to make the South African side.

Well, one can argue that Charlie Llewellyn, that famed all-rounder who played for the South Africans at the turn of the last century, was the first non-white cricketer to play for the land. But the claim was disputed, by none other than Llewellyn's own daughter, and the actual facts have become blurry with the passage of time.

Man in the Middle

Yes, he played against the Australians – alongside Clive Rice, James Cook, Brian McMillan, David Richardson and Garth le Roux. However, there were Apartheid laws he had to deal with. He could not stay in the same hotel as the team, could not eat in the same restaurants. When he tried to break these barriers, he was physically chucked out. He was a teetotaller, but he had the liquor law thrown in his face to evict him – the curious law that said no non-white should be served liquor in a public place. He played on.

When finally the day dawned that saw South Africa being accepted back in the fold of international cricket, the path-breaking tour of India was organised. Rice led his men to play three One Day Internationals (ODIs) in the country where no South African cricketer had ever played international cricket. Henry was by then pushing 40, and lost out to Tim Shaw for the slow bowler’s slot in the side.

However, when the subsequent team was announced for the 1992 World Cup, Shaw was dropped and Henry was the most welcome and popular of choices. At Wellington, he made his debut against Sri Lanka, finishing with excellent figures of 10-0-31-1.

The South African team travelled to West Indies to play three ODIs and the first ever Test since re-admission. Henry played in two of the ODIs without much success. After that he fell ill, thus missing the thrilling Test at Barbados.

He was 41 when India visited in 1992-93. And he was picked for the Test at Durban.

As was expected, the inclusion of a non-white spinner in cricketing middle age was widely interpreted as window dressing. However, Henry was extremely fit, and in the three First-Class matches leading to the Tests, had taken 17 wickets, including a first innings haul of six for 72 against Natal. In the match against Eastern Province, he had captured just two wickets in 34 overs, but had scored 79 with the bat. He was the spinner in form and a decent batsman to boot. He deserved his place in the side. Mike Procter later wrote: “No way was he in the team just so it would look good.”

As he took field on November 13, 1992, he became the first coloured cricketer to play a Test match for South Africa. It made him a symbol for what could be achieved in the new Rainbow country. In the game, Henry was brought on late, showed some signs of nerves by overstepping three times in spite of his short run up. But, he ended the innings with the quick wickets of Anil Kumble and Kiran More, finishing with two for 56 from 19 overs.

He played in two more Tests in the series, and managed to scalp just one more wicket. But, he had secured his rightful place – as the pioneer in the journey of his people in South African cricket.

Immediately after the Test series, Henry guided Orange Free State to the Currie Cup championship with an innings of 104 followed by two for 42 and five for 68 against Western Province. Later, justifying his inclusion in the Test team, Procter wrote, “Don’t forget that at the end of the 1992-93 season, he was named Man of the Match in the Currie Cup final after guiding Orange Free State to the first title in history.”

Henry played just one more season after that. Following his retirement, he has been involved in spotting talented young cricketers in the country. For a brief duration, he also acted as the convenor of the South African selection committee.

Way past his heydays when he finally played international cricket, Henry had to be satisfied with meagre returns in three Tests (three wickets at 63.00) and three ODIs (two wickets at 62.50). However, his First-Class figures reflect the reason why he could break the apartheid bastions and become a member of the South African side in the high noon of racial divide. In 131 First-Class games, he scored 4566 runs at 27.34 with five hundreds and captured 443 wickets at 25.17. In his prime, he was more than a handy all-round cricketer.

There have been many non-whites who have made it to the national team since then. Some have achieved enormous success, as in the cases of Hashim Amla and Makhaya Ntini. Ashwell Prince has even gone on to captain the South African team. However, such eventualities had remained in the realms of dream and speculation until the day Omar Henry had walked into the national side, leaping across racial barriers and sending down his looping left-arm spinners.