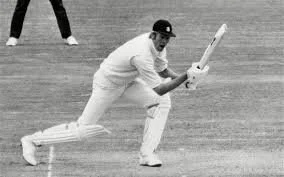

Tony Greig, born October 6, 1946, was one of the most talented and colourful cricketers in the history of the game. Abhishek Mukherjee looks back at the career of the cricketer who helped shape professional cricket the way it is today.

He is truly a global citizen. A South African by birth, Scottish by paternal descent, Tony Greig captained England and later settled down in Australia.

A career aggregate of 3,599 runs at 40.43 and 141 wickets at 32.20 in a career spanning only five years indicates Greig’s stature as one of the finest all-rounders of the game, Greig is only one of few to a handful to have scored 3,000 runs and taken 100 wickets in Tests.

Yet, it is often not the performances on the ground that we remember Tony Greig for.

Early days

When Greig was in college, a group of Sussex cricketers — including Test players like Alan Oakman and Ian Thomson — visited his native Queenstown. Greig, making his debut for Border at the age of 19, impressed the visiting Sussex members enough and was offered by them a place in the county side. After much deliberation and encouragement from his father, Greig gave up his University pursuits and left country for England.

After a string of matches for Sussex Second XI with mixed results, Greig got picked for Arthur Gilligan’s XI against the touring West Indians in 1966. Playing against some of the biggest names in international cricket, Greig dismissed Seymour Nurse and Rohan Kanhai to return figures of 3 for 51.

Early in the following year he got picked to play Lancashire at Hove. Coming in at 34 for 3, Greig counterattacked from the very beginning. No one else went past 32 as Greig scored 156 in 230 minutes on debut to lift Sussex to 324 against a bowling attack that consisted of Brian Statham, Ken Higgs and Peter Lever.

He never looked back from there. His medium-paced bowling complimented his batting well, and Greig soon became one of the backbones of the Sussex side. He also turned up on a regular basis for Border in the English off-season, thereby keeping both options open.

Picked to play for England against the touring Rest of the World XI in 1970 Greig shone at the first opportunity: he took 4 for 59 and 3 for 71 (including Barry Richards, Eddie Barlow and Sobers in both innings). He played 2 more matches in the series, and it was inevitable that he would make his Test debut very soon.

A world champion

Before playing a single Test, though, Greig was picked for the World XI to play in Australia and played in all 5 matches.

After a quiet game at Brisbane, he came to his own at Perth: before Dennis Lillee decimated the tourists with some really hostile fast bowling, Greig picked up 4 for 94; he followed that 4 for 41 at Melbourne before Sobers snatched victory after a 101-run deficit; up against 321 at Sydney he scored 70 coming in at 61 for 5 to save the game. And opening bowling in the first innings at Adelaide, Greig routed the Australians with 6 for 30, paving the way for Graeme Pollock, Bishan Bedi and Intikhab Alam in the second innings to win them the match. In the 10 First-class matches he played on that tour, Greig ended up with 525 runs at 37.50 and 26 wickets at 25.53.

He went to South Africa to resume domestic cricket later that year. He had switched to Eastern Provinces by now. He began the first match with his World XI bowling partner from Adelaide – Peter Pollock – and picked up 5 for 39. Everything was going fine before he had an epileptic seizure during the match, and six players were required to restrain his 6’6″ frame. It was something he was suffering since his teenage days. However, the incident did not gain much publicity, and Greig’s general all-round performances for Sussex ensured that he would make his Test debut at Old Trafford later that year.

It was a dream debut. Like always, Greig had reserved his best for the biggest of occasions (his Test average of 40.43 was significantly better than his overall First-class average of 32.20). With Boycott injured, Greig came in at 99 for 3 (virtually 99 for 4), and soon found his side struggling at 127 for 5. Once again the pressure brought out the best in him: he top-scored with 57 and added 63 with Allan Knott to lift England to 249. He played his hand, dismissing Ian Chappell first ball, as John Snow and Geoff Arnold routed Australia for 142. He top-scored yet again with 62 against a rampant Lillee. And when Australia chased 342, Greig took 4 for 53, assisting Snow to bowl them out for 252.

The Test made Greig an instant celebrity in the world of cricket. This was the first time England had won the first Test of a home Ashes series since Trent Bridge 1930. Though Greig had a quiet series after Old Trafford he ended up second (after Barry Wood) on the batting chart with 288 at 36, and also played his part with the ball.

Indian tricks

England toured India next, and Greig had a long spell of 23-8-32-2 (wickets of Gundappa Viswanath and Eknath Solkar) to assist Arnold to bowl out India for 173 in the first Test at Delhi. Coming in at 71 for 4, Greig top-scored with an unbeaten 68 shepherding the tail to take England to 200 as Bhagwat Chandrasekhar took 8 for 79 in a marathon spell. This included a spectacular six off Chandra over extra-cover. Chasing 207, England were struggling at 107 for 4 against Bedi and Chandra when Greig joined captain Tony Lewis. Lewis remained unbeaten on 70 and Greig on 40 as England reached home.

Underrated as a bowler

In the next Test at Calcutta, Greig once again stood high amidst ruins. He started off the Test rather innocuously with 1 for 13 and 29 as India took a lead of 36. Then, with India going strong at 104 for 2, Chris Old (4 for 43) and Greig (5 for 24) made inroads as India were bowled out for 155. The Indian spinners got England into trouble almost immediately, and Greig found himself coming out at 17 for 4. Once again, Greig played a supreme counterattacking innings, and England reached stumps on Day Four at 106 for 4. However, Chandra dismissed Greig for 67 with a top-spinner early on the final day. Chandra and Bedi went on to plot England’s defeat by 28 runs.

It was roughly at this time that Greig had started his experiments with off-breaks. He scored his first Test hundred (148) at Bombay later that series, coming in at 79 for 4 after India had scored 448. He added 254 with Keith Fletcher, and though England lost the series 1-2, Greig shone by topping the batting charts with 382 at 63.66 and coming second in the bowling list with 11 wickets at 22.45, next to only Arnold.

The Calypso saga

Greig had a decent away series against Pakistan (261 runs at 52.20; 6 wickets at 42.50) and a very good home series against New Zealand (216 runs at 43.20; 8 wickets at 23.12). He left for an away tour of the West Indies. He did not do well in the home series against West Indies that followed. West Indies gave England a 2-0 drubbing in 3 Tests (both victories were comprehensive ones), and Greig had a very ordinary series with both the bat and the ball.

However, it was in the next series that Greig made headlines for all the wrong reasons. not for the first time in his illustrious career. After Keith Boyce had routed England for 131 in the first Test at Queen’s Park Oval, the tourists fought back with bravado. However, Alvin Kallicharran defied them with a brilliant innings, well-supported by Bernard Julien. As Julien had played out the last ball of the second day, both batsmen left for the pavilion before umpire Douglas Sang Hue actually called “stumps”. Greig swooped down on the ball and broke down the stumps at Kallicharran’s end, and Sang Hue had no option but to rule him out.

The crowd laid siege on the ground in a vehement protest, creating a blockage on the players’ route back to the pavilion. Whatever Greig had done was perfectly within the rules, but he was called “unsportsmanlike” by all and sundry. Mike Denness, the England captain, had no option but to recall Kallicharran the next morning.

The incident marred Greig’s image to some extent, but this was probably the series that firmly established him as the world’s leading all-rounder with Sobers’s career coming to an end. After 2 quiet Tests at Port-of-Spain and Kingston, Greig came to his own at Bridgetown. Coming to bat at 68 for 4, Greig scored 148 against Bernard Julien and mates, adding 163 for the sixth wicket with Knott. West Indies hit back strongly, with Lawrence Rowe scoring 302, but Greig bowled on relentlessly — he was a full-time off-spinner by then — taking the first 4 wickets and eventually 6 for 164. He followed this with 121 and 2 for 57 (Roy Fredericks and Rowe) at Georgetown, but after 4 Tests West Indies still led the series 1-0.

Geoff Boycott scored a dour 99 to raise the tourists to 267 in the fifth Test at Port of Spain. Pat Pocock, in an inspired spell on the second afternoon, removed both Fredericks and Kallicharran. Greig, after opening bowling, had switched to off-breaks, but could not extract a lot of help from the track, finishing with none for 53 from 17 overs. Rowe, with the help of Clive Lloyd, had helped West Indies read 224 for 2. In a burst of twenty balls, Greig removed Lloyd, Sobers, Kanhai and Deryck Murray in the space of just 5 runs. He took the last 4 wickets as well, and returned a haul of 8 for 33 from 19.1 overs on the third day. His 8 for 86 was the best innings figures against West Indies by an England bowler, going past Trevor Bailey’s 7 for 34 at Kingston in 1954.

Boycott scored 112 this time, leaving the hosts 226 for a victory. Despite the presence of Derek Underwood and Pocock, it was left to Greig to take charge. Greig toiled on, opening the bowling and then reverting to off-breaks, removing Kallicharran, Lloyd, Kanhai and Murray to leave West Indies reeling at 161 for 8. Boyce then added 36 with Inshan Ali before Denness had to take the second new ball. Switching to medium-paced bowling, Greig removed Inshan Ali immediately, and England ended up winning the Test by 26 runs and squaring the series. Greig finished with 33-7-70-5, and finished with 13 for 56 from the Test. This was the best match statistics for any England bowler since Jim Laker’s historic performance against the Australians. With 430 runs and 24 wickets from the series, Greig came second on both charts for England.

Ashes attacks

In the next season, Greig had decent outings against both India and Pakistan at home before flying to Australia for the Ashes. The hard pitches did not suit his style of bowling very much, and he remained generally unsuccessful. However, he did well with the bat. Australia went up 4-0 in the first 5 Tests, and 42-year old Colin Cowdrey had to be flown out to support an England side that had been hit hard by the pace of Lillee and Thomson. He batted well in bursts, scoring 110 (coming out at 57 for 4) in the first Test at Brisbane. However, in the sixth Test at Melbourne, Greig took 5 for 123 and scored 89 to lead England to an innings victory to salvage some pride.

En route home, England visited New Zealand, and after Greig scored 51 in a mammoth 593 for 6, he took 5 for 98 and 5 for 51 to rout the Kiwis by an innings. On his return, Greig had another epileptic fit at Heathrow Airport. This made the ailment public. However, there was no stopping Greig, who defied his country of birth to make it as the Test captain for the upcoming Ashes, less than five months from the previous one after England’s rather ordinary show at the 1975 World Cup under Mike Denness.

This was another average Ashes series by Greig – 284 runs and 8 wickets in the series seemed almost a letdown for the great man, More so since England went on to lose the series 0-1. In the second Test at Lord’s, though, he shone with 96 and 41, and 3 wickets, and then scored 51 and 49 at Headingley. With Australia 1-0 up in the series and 220 for 3 at stumps on Day Four, having lost both Chappell brothers, England looked all set to go for the kill on Day Five.

However, a man George Davis was arrested earlier that year for an armed payroll robbery of the London Electricity Board on April 4, 1974. When he was serving a 20-year notice, his supporters dug up the Headingley pitch on the fourth night using knives and poured oil in the resulting cracks, thereby ensuring that no play was possible on Day Five. Greig had no option but to have the match abandoned. The last Test was a draw, and Australia retained the rubber.

Grovel!

The Australians seemed unstoppable: they went on to thrash West Indies by a whopping 5-1 margin, and just before West Indies toured England in 1976, Greig uttered the following words during a televison interview:

“You must remember that the West Indians, these guys, if they get on top are magnificent cricketers. But if they’re down, they grovel, and I intend, with the help of Closey and a few others, to make them grovel.”

Had this been a remark by someone else by some other side this might not have had the serious impact it had. However, given the fact that a significant part of the West Indian population had slave ancestry and the fact that Greig actually came from South Africa – a place where apartheid still reigned supreme – Lloyd and Co. took the word grovel rather seriously, though probably none more than Viv Richards.

The impact was stunning. Richards scored 829 at an average of 118.42 and a strike rate of 70, and both Fredericks and Gordon Greenidge also amassed more than 500 runs in the series. All four fast bowlers – Michael Holding (28 wickets at 12.71), Andy Roberts (28 wickets at 19.17), Wayne Daniel and Vanburn Holder – had sub-25 bowling averages. West Indies won the series 3-0, and eventually, when the English side was battered both physically and psychologically, took stage at The Oval, the Test turned out to be a mini-summary of the series: Richards scored 291 as West Indies scored 687 for 8; Holding took 8 for 92 (6 bowled; 2 LBW) to bowl out England for 435; West Indies declared at 182 without loss in 32 overs. And then, Holding ran amok again, taking 6 for 57 to bowl out England for 203. It was a fitting ending to a perfect annihilation.

India, again

It seemed that Greig’s career as a captain was over after the complete rout in the hands of the Caribbeans. However, the selectors decided to give Greig another chance in the tour to India later that year. John Lever, on his debut, began the rampage: he took 10 for 70 to win the Delhi Test by an innings. Greig had a quiet Test.

At Calcutta, however, Greig came in his elements. After Greig lost what looked like a must-win toss, Bob Willis bowled out the Indians for 155 on a pitch full of cracks before Bedi and EAS Prasanna had India reeling at 90 for 4. There was some doubt regarding Greig’s availability, since he was down with a severe stomach bug. But Greig emerged from the pavilion to join Roger Tolchard with a weak physique and running a high fever.

The 7-hour stay at the wicket that followed in extremely demanding physical conditions is regarded by many as Greig’s career-best batting performance. Visiting batsmen have always considered batting in the cauldron-shaped Eden Gardens in front of a 100,000-strong crowd a challenge: with the host spinners on a roll, it was even tougher.

But Greig battled on. He added 142 with Tolchard and 64 with Old to bat India out of the match. It was an uncharacteristically dour innings, but according to Greig, given his physical conditions, he could merely hold on for survival — especially on an almost unplayable pitch that was turning square. Not content, he bowled 10 overs, removing Viswanath and Anshuman Gaekwad to make early inroads into the strong Indian batting line-up. India managed to avoid an innings defeat, but still went on to lose by 10 wickets.

Greig could bowl only 4 overs in the next Test at Madras: however, he still scored 54 and 41 in a low-scoring affair where Lever, Underwood and Willis led England to a 200-run victory to seal the series for England. India fought back to win the fourth Test at Bangalore, and England had managed to hold on to a close draw in the final Test at Bombay to end up in a 3-1 series win. Greig had redeemed himself.

Greig led England for one final time in the Centenary Test at Melbourne in 1977. Both sides had decided to play some aggressive cricket: after being bowled out for 138, Australia bowled England out for 95, Lillee taking 6 for 26. Rodney Marsh then flailed his bat to score an unbeaten 110, and Rick McCosker braved a broken jaw to bat at 10, hanging around for over an hour to score 25. Chasing 463, Derek Randall led a furious onslaught, scoring 174, with four other batsmen including Greig (who had a nice all-round display, scoring 18 and 41, taking 2 wickets and 4 catches) crossing 40, but England lost the Test by 45 runs – the same margin as they had lost the first ever Test exactly a hundred years back!

Packer, and more…

On this trip, however, Greig had built up his contacts with Kerry Packer, and was instrumental in signing both English and others (mainly South African) cricketers for World Series Cricket. He had tried to keep the entire thing a secret, but the news became public. Greig tried to defend World Series Cricket, and with the players’ support, went on with the signings: as a result he was sacked as a captain but was surprisingly retained in the side.

In his last series, playing under Mike Brearley, Greig helped England to their first Ashes victory during his time. He did not really dominate a match, but scored 91 at Lord’s, 76 at Old Trafford and 43 at Headingley. He also took 7 crucial wickets from 5 Tests at 28, and England romped to a 3-0 series win. This turned out to be Greig’s last series.

The tycoon and his general

He continued to play World Series Cricket for some time without much success; however, he was instrumental in assisting Packer in setting up World Series – getting the players to sign up the contracts and setting up the entire tournament. When today’s players earn unthinkable fortunes in privately organised tournaments, one should remember that it is all due to Packer and Greig three and a half decades back. They had brought about the most crucial change in the history of the sport — perhaps even more than Douglas Jardine.

As a token of gratitude towards his immense contribution to World Series Cricket, Greig was offered a “lifetime job” as a commentator for Packer’s Channel 9. He moved to Australia later. His overenthusiastic style did not impress the puritan, but he continued to remain immensely popular with the microphone all over the world.

Tony Greig passed away on December 29, 2012.