The Gentle Giant

Vintcent van der Bijl, born March 19, 1948, was one of the greatest fast-medium bowlers of all time. Abhishek Mukherjee looks back at yet another talented cricketer who did not make it to the top level because of South Africa’s isolation from international cricket because of their Apartheid policy.

City Oval, Pietermaritzburg, 1972. After Natal had won the toss and had elected to bat, Robin Jackman and Peter Swart bowled them out for 76 on the first morning — Jackman registering a hat-trick. The Western Province side was expected to put up a big lead and bat Natal out of the match as Neville Budge and Quentin Rookledge walked out to bat.

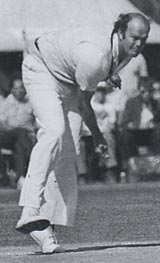

Then, from the shadows of the canopy of trees, emerged a tall frame of 6 feet 7½ inches, in size 14 boots. He did not snarl as he ran in. If anything, there was a hint of a smile in those twinkling eyes. He did not pound the turf as he approached the non-striker’s end — he simply flowed like a river in a silken motion that evoked more poetry than power. There was nothing intimidating about the imposing figure. Other than his accuracy, pace, bounce, and movement off the pitch, that is.

Before they realised what had hit them, Western Province were bowled out for 121. Vintcent van der Bijl had taken 8 for 35 from 22.2 eight-ball overs. After Barry Richards helped Natal to 263 in their second outing, van der Bijl came back at Western Province again, taking 5 for 18 from 14 eight-ball overs, bowling them out for 60. Seldom has a side won by a huge margin —158 runs in this case — after being bundled out for 76 in the first innings.

There has been only one van der Bijl. The world has seldom seen a better fast-medium bowler. And yet, having born at the wrong place in the wrong time, he could not play a single Test. Ever. This meant that he had to spend an entire career lurking in oblivion, unnoticed by the cricket world. When people speak about the South Africans of the 1970s, it’s usually about Barry Richards, Graeme Pollock, Peter Pollock, Mike Procter and Clive Rice. Few people mention van der Bijl.

Not that he minded. A teacher at Maritzburg College, Pietermaritzburg, he never took up cricket as a profession. It was always a form of entertainment for him — and another sport that he had chosen over rugby and shot-put, both of which he was extremely proficient at.

He was never rude, or even aggressive. Such attributes were well beneath him; off the field, the genial giant greeted everyone with the most cordial of smiles, and won friends everywhere. Seldom has a pace bowler been as apologetic after bouncing; or as good-humoured after being clobbered by a batsman.

How great was van der Bijl?

Let us do some number-crunching first: In 156 First-Class matches, van der Bijl took 767 wickets at a staggering 16.54. He had 46 five-fors in these matches, which was once every 3.4 matches. He played First-Class cricket in 16 seasons — which included a single match each in two seasons. In the other 14, his worst average was 21.33 in 1972-73, and he went past the 20-mark only once more — in 1976-77.

Van der Bijl is still the leading wicket-taker in Currie Cup with 572 wickets; the next man on the list is Garth le Roux with 365 wickets — a whopping 207 behind van der Bijl. He took 65 wickets in a South African domestic season in 1975-76 — a record at that time. If one considered non-Test playing cricketers after World War I, van der Bijl has the most wickets, and the best bowling average (with a 200-wicket cut-off) in First-Class cricket.

The home seasons

Vintcent van der Bijl was a third-generation First-Class cricketer. His father, Pieter, had played 5 Tests for South Africa. Pieter had scored 460 runs at 51.11, and had once held the record for the longest Test innings by a South African when he batted for 428 minutes. It was probably from him that Vintcent had inherited his talent — and his incredible sense of humour.

He impressed everyone at university level, and caught the eyes of Trevor Goddard. Goddard and Peter Pollock guided him, and they were so impressed that van der Bijl leap-frogged into the Natal side, not having to play for the second team.

Turning up for Natal, van der Bijl made an immediate impact on the domestic circuit. He took 24 wickets at 20.54 — excellent figures by any standards — though it was way below par in van der Bijl’s standards. He went a step ahead in the next season, picking up 28 more at 15.60.

Even then, he could not find a place in the 1969-70 home series against Australia. So strong was the South African team that van der Bijl was not even in contention. However, he could not be kept out for long, and after 26 wickets at 19.53 and 48 wickets at 15.10 in the next two seasons, he was an automatic selection for the 1971-72 tour to Australia.

The tour did not take place, though; South Africa was banned from international cricket, and van der Bijl’s dreams of playing Test cricket were shattered forever. He kept on teaching in the off-season, and made merry at the hapless Springboks’ expense in the South African domestic circuit.

He ran in, over after over, match after match, season after season, never tiring, despite knowing that he would never be able to play Test cricket for a fault that wasn’t his. For him, cricket wasn’t a way to find his recognition in the world, or a mode to vent out his anger or frustration. In van der Bijl’s world, cricket was meant to be fun.

His father had once written to him “whether you make runs or take wickets, or do neither, always think of the other fellow”. He never failed to do that. When Barry Richards had asked van der Bijl to bounce a tail-ender on one occasion, he gently replied “but I might kill him, Boer.” It will indeed be difficult to explain the van der Bijl philosophy to fast bowlers of the current era.

He became the captain of Natal in 1976-77, and in his first season he led them to victories in both the Currie Cup and Datsun Shield (the South African domestic limited-overs tournament). He worked on his batting at the same time, and scored three fifties in the 1978-79 season, and three more in the following one — along with 46 wickets at 14.86 and 37 more at 13.59 in the two seasons.

All this happened when Imran Khan, Kapil Dev, Ian Botham, and Richard Hadlee had all appeared on the international scenario, along with the West Indian pace battery. van der Bijl could only remain a silent spectator, just like his countrymen Clive Rice and Mike Procter — though he deserved playing cricket at the highest level more than most. As Barry Richards had said once, “Vince van der Bijl is one outstanding example of somebody who would have been a wonderful international player.”

Stint with Middlesex, and later years

In 1979 van der Bijl had quit teaching, and began working for Wiggins Teape. However, with West Indies scheduled to tour England in 1980, the Middlesex team management assumed that their spearhead Wayne Daniel would be on national duty, and they sought a replacement. They signed up van der Bijl.

The Middlesex players were not happy. Mike Brearley showed his dissent at his selection, and was ready to raise it to the Committee. John Emburey asked, “who the hell is this van der Bijl guy?” Indeed, other than his superlative bowling average (that too in a country with an unknown quality of cricket), he had nothing to show on his CV. He was 32, had almost never played in England, and was probably out of practice in what was an off-season for his country.

At the first glimpse of van der Bijl, Ian Gould told himself “how’s this old man going to cope?” He was sure that it had been an ‘outrageous signing’. After the season Gould went on to remind “he became a Middlesex legend and he was there for only a season.”

As things turned out, Daniel did not get selected for West Indies, and van der Bijl opened bowling with him against Nottinghamshire. It was a rendezvous for fast bowlers, since Richard Hadlee and Clive Rice were playing for Nottinghamshire. van der Bijl’s first ball pitched on the leg-stump, moved off the pitch, beat the bat, and thumped into Gould’s gloves. van der Bijl had arrived!

van der Bijl picked up 4 for 62 and Daniel 4 for 59, and Nottinghamshire were skittled for 164. At stumps, he entered the Nottinghamshire dressing-room with a beer, and immediately realised that he was in for a cultural shock. They did not fraternise with opponents in England.

He won over a lot of supporters, both among his teammates and the crowd, both with his quality of cricket and his attitude towards the sport. His captain Mike Brearley wrote in The Art of Captaincy: “… we were lucky enough to have van der Bijl in our side; his contribution was immense, not only on the field but off it: for he tended to blame himself rather than others, and saw the best in the rest of us rather than homing in so sharply on faults. After a poor performance in the field against Kent in a Sunday League match, for instance, it was refreshing to hear van der Bijl say, ‘Sorry, men, it was all my fault, bowling those two half-volleys early on.’”

Daniel, the other Middlesex spearhead, hit off with van der Bijl almost immediately. When the lanky South African got a wicket, the Barbadian ran in to greet and hug him with a wide grin, thereby ignoring the political issues that had made the countries avoid looking at each other in their eyes. “It was like a bear hugging a giraffe, and it was symbolic of the warmth most West Indians showed South African players”, writes Simon Hughes.

Hughes adds: “No one could fail to be impressed by van der Bijl. Not only was he a fearsome bowler with incredible accuracy, genuine penetration, and an LBW appeal like an enraged triffid, but off the field he was also gentle and disarming, intelligent and funny.”

His self-control and sense of humour showed in the most adverse of times as well. When Sunil Gavaskar was belting him mercilessly in a Benson and Hedges match, van der Bijl found the Little Master’s bottom edge — only to watch it run away for four. It was the first time Gavaskar had erred in that innings. van der Bijl, about a foot and a quarter taller than Gavaskar, walked up to the little man and feigned fury, exclaiming “Oh, you ‘orrible little man, why don’t you concentrate?” Everyone, including the usually sombre Gavaskar, was in splits.

To put things short, van der Bijl had fun, smoked Dunhills, and took 85 wickets in the season from 20 matches at 14.72. He took 5 five-fors, and in combination with Daniel (67 wickets at 21.70), led Middlesex to the County Championship and the Gillette Cup. He was nominated a Wisden Cricketer of the Year in 1981.

Hughes mentions that he was “very accurate, and [had] a wicked yorker, amazing control and a classic side-on action.” His accuracy had become the talk of the town. Gould recalls an incident where van der Bijl was bowling on a damp pitch. After his first over, Gould wanted to check where the balls had landed, making dents on the soft earth. It was then he realised that all six would have ‘landed on a saucer’. An awestruck Mike Selvey called him ‘fantastic, relentlessly straight’, possessor of ‘Southern Hemisphere strength’, and he was indeed one of the best bowlers he had seen.

He returned home a hero, having established himself among the world’s greatest players. There had never been any doubt in his home country about his ability — and now the world of cricket had become aware of his supreme pedigree. Bolstered by his success, he blew apart the South African batsmen, match after match, picking up 54 wickets from eight matches at an absurd 9.50.

He had become so popular in Middlesex that he was recalled for a single match against MCC in the 1981 season. He did little of note, but he was greeted with the rare loud cheers of the typically quiet of Lord’s that behaved against its nature out of loyalty to the great man.

In the last match of the domestic season, van der Bijl won the encounter for Natal against Northern Transvaal single-handedly as he took 6 for 64 and 8 for 47. When the rebel Englishmen toured South Africa in later that season, van der Bijl was picked to play for South Africa. Against a strong batting line-up comprising of Graham Gooch, Geoff Boycott, Wayne Larkins, and Dennis Amiss, van der Bijl took 5 for 25 and 5 for 79 to blow them apart. He had another spell of 5 for 97 in the same series. He shifted to Transvaal the next season.

The change of team hardly made any difference to him, and he finished the season with 75 wickets from 11 matches at 14.92. He played two matches against the rebel West Indies team, picked up 10 wickets at 18.80. And then, all of a sudden, he decided to call it quits after the 1982-83, in which he took 52 wickets at 18.76. His match figures in his last four matches read 6 for 93 against Eastern Province, 9 for 91 against Eastern Province, 3 for 39 against Natal, and 7 for 132 against Western Province.

Later years

van der Bijl generally remained away from cricket after his retirement from First-Class cricket. Over time, he came to terms with the fact he had not been able to play a single Test, and generally remained away from cricket. Even after South Africa’s return to international cricket, he never got the recognition he had deserved — unlike several of his contemporaries. Not that it bothered to him.

It was as late as in 2008 that ICC named him their Manager for the umpires and match referees.