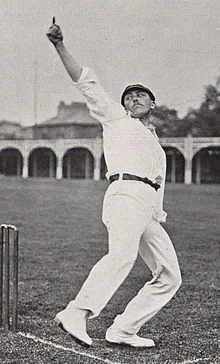

Wilfred Rhodes (born October 29, 1877) was a great left-arm spinner who also made himself into a top class opening batsman. Arunabha Sengupta pays tribute to the man who has inspired some of the greatest cricket literature.

According to Neville Cardus, “He was Yorkshire cricket personified”. He was shrewd, dour, played hard and was not given to affability on the field. Yet, when one met him after his retirement, tales of cricket flowed from his tongue, unabated like a perennial and joyful river.

Wilfred Rhodes was a gifted all-rounder – a left arm spinner and a self-made batsman. He scored 31 short of 40,000 runs in First-class cricket with 58 centuries. Yet, his more important duty was to roll his arm over again and again, which he did with considerable relish, for 1110 matches, picking up a colossal 4204 wickets at 16.72.

No one has taken more wickets in First-class cricket.

George Hirst, Wilfred Rhodes and the Unforgettable Test

His fellow Yorkshire professional George Hirst scored 36,356 runs and claimed 2742 wickets.

In his book, Hirst and Rhodes, AA Thomson asked: Who is the greatest all-rounder? He also provided the answer: “Nobody knows, but he batted right-hand and bowled left, and he came from Kirkheaton.”

The sentence was apt for both – Rhodes, the left-arm spinner, and Hirst, the left-arm medium pacer. It was way before the time of Garry Sobers, but gives us a snapshot of the enduring appeal of the two great men.

In an introduction to the same book, JM Kilburn called Wilfred Rhodes “the one-man university of the game.”

In the famed Oval Test match of 1902, Gilbert Jessop carried England to the brink of victory with an explosive century, and Hirst and Rhodes found themselves at the crease as the last pair, 15 runs away from the target. Did Hirst really go up to his Yorkshire teammate and say, “Let’s get them in singles?” No one can vouch for it. Perhaps it was written with the characteristic nonchalant wave of the poetic license as Cardus performed his alchemy with words to turn cricketing feats into folklore.

Indeed, Rhodes later told biographer Sydney Rogerson, “That would be a ridiculous thing for him (Hirst) to say! It would mean that I should have to take as much of the bowling as he would, and he was well set!”

But, get those 15 runs they did – to clinch one of the greatest wins of all time.

Eighty something years later, Stanley Shaw wrote a novel – Sherlock Holmes at the 1902 fifth Test. According to the story, but for the great detective Wilfred Rhodes would not have been present at the Test on the fifth day. Such was the undying legend of the Test, Hirst and Rhodes.

The bowler and the batsman

While performing relentless service for Yorkshire, it was almost in his spare time that Rhodes turned out for England. Yes, he did come in as a No 11 at the beginning, from where he put on 130 for the last wicket with Reginald ‘Tip’ Foster at Sydney in 1903.

By 1912, however, he had worked his way up the order, opening the batting and putting on a record 323 with Jack Hobbs. He is one of the three men to have batted at all eleven positions in Test matches.

However, he was primarily a bowler – of uncanny accuracy and flight. It was again Cardus who described him thus, “Flight was his secret. Flight and the curving line, now higher, now lower, tempting, inimical; every ball like every other ball, yet somehow unlike; each over in collusion with the others, part of a plot…every ball a decoy, some balls apparently guileless, some artfully masked, and one of them sooner or later the master ball.”

During the first five years of his career, he had made the most of his youth and early ability to turn the ball with some sterling bowling efforts. Seven for 17 at Birmingham in 1902, and seven for 56 and eight for 68 in two innings of the same Test at Melbourne in 1904 were some of his best efforts. The Australians were at the receiving end on each occasion.

While he spun the balls in England, he hardly purchased turn on the Australian grounds. But that did not deter him. He varied his length, subtly changed his flight, and was uncannily accurate.

In December 1903, at Sydney, Australia scored 485 in the second innings on the shirt-fronted polished Bulli soil pitches of that distant halcyon day for batsmen. Victor Trumper, that “Prince of Batsmen”, was at his height of fluent majesty, holding court even amidst the immense brilliance of Reggie Duff, Syd Gregory, Clem Hill, Monty Noble and Warwick Armstrong. Trumper stroked his way to 185 not out, but Rhodes took five for 94 off 40 overs. And it provoked Trumper to exclaim,“For God’s sake, Wilfred, give me a minute’s rest.”

To the end of his days, Rhodes claimed that he had never been cut or pulled. Exaggeration though it undoubtedly is, it does underline that he seldom, if ever, pitched short.

Later in his career, when his fingers could not turn it as sharply as in the days of youth, he could work on the batsman’s weaknesses like none other. Besides, he stuck meticulously to his field. Ernest Tyldesley once remarked that he often had no alternative but to play at least three balls an over, on a batsman’s wicket, straight to mid-off, an inch off the spot where Rhodes had planted mid-off.

His batsmanship, on the other hand, was a self-taught trade – performed and perfected with common sense and a lot of application. It was never a thing of beauty – EW Swanton maintaining that he was a craftsman rather than an artist. He played straight, relying on the drive and eschewed the cut – which he felt was ‘never a business stroke’. However, he elevated his returns with the willow to a level that made him the default choice to partner Hobbs at the top of the English batting order.

As he transformed himself into a batsman, his bowling was more sparely used. In the Melbourne Test match of 1912, when he scored 179, adding 323 with Hobbs, he bowled only two overs.

Post-War

When the Great War brought cricket to a screeching halt, he already had a great career behind him – 14 years of Test cricket, with 1965 runs at 32.21 and 105 wickets at 24.90 from 47 Tests. And when the mindless destruction ended, a depleted Yorkshire needed Rhodes to bowl his left- arm spinners again. At 42, he responded, as if nothing had changed. He ran in his four paces, arched his body and flighted it – slow, precise and accurate –over after over.

He toured Australia too in 1920-21, but could manage just four wickets in five Tests, at an average of 61. And apart from one innings of 73, there was not too much to show for his efforts with the bat either.

So he concentrated on bowling for Yorkshire, the very task which he seemed born to perform. Yet, after another half a decade, he was once again called by England.

By then he was 49. With the series locked at 0-0 after four Tests, he was asked to impart the decisive spin for the English cause, at the same Oval where he had collaborated in that famous victory twenty-four years earlier.

He responded with two for 35 and four for 44. In the first innings he got Bill Woodfull, in the second, Bill Ponsford, Herbie Collins and Warren Bardsley. In the last encounter with the old foe, he scooped out the cream from the fare. England won by 289 runs.

Cardus wrote: “He had probably lost by then much of his old quick vitally fingered spin: but as he explained to me: “If batsmen thinks as I’m spinnin’ them, then I am” — a remark metaphysical, maybe, but to the point.”

He continued to play for Yorkshire, turning his arm over tirelessly. In 1929–30, he was selected in a MCC team to tour West Indies. Rhodes described it as an “old crocks” team, since it included several veteran cricketers.

On the tour he was over-bowled, and although he was fairly successful in the tour matches, in the four “Representative Games”, which were later given Test status, he took just 10 wickets at 45.30. On the final day that he spent playing Test cricket, Rhodes was 52 years 165 days old, a record that is likely to stand forever.

He ended his Test career with 2325 runs at 30.19 and 127 wickets at 26.96 from 58 Tests.

Rhodes retired from First-class cricket in 1930, leaving the Yorkshire left-arm spinner’s post in the more than capable hands of Hedley Verity.

After calling it a day he continued to be close to the game, coaching Yorkshire for several seasons.

Later, even after losing his eyesight, he continued to attend Test matches, able to follow the proceedings with his keen sense of hearing.

One often noticed the familiar figure in the stadium, listening intently each time the willow struck the leather .And during breaks he regaled the delighted audience with cricketing tales as few could – a cricketer who himself was an established monument in the landscape of the game.