Zaheer Abbas, born July 24, 1947, was one of the greatest batsmen of Pakistan and among the most graceful strokemakers with an insatiable appetite for runs. Arunabha Sengupta looks back at the career of the man who was the first Asian batsman to score 100 First-Class centuries.

Glory of Gloucestershire

Gloucestershire is a county that invokes images of the epitome of elegance and grandeur in batsmanship. Way back in history it was the shire of the Graces, with the great WG revolutionising the art and craft of wielding the willow with his front and back play. Down the years, the county saw giants walk out and amass runs for them, with supreme style and grace, with the perfect cover-drive that seemed the signature of the county ground.

Wally Hammond batted for the side, and when he retired in stepped Tom Graveney. Class flowed through the field, especially the covers. By the early 70s, as Graveney faded from the scene, it was perhaps appropriate that the county management looked beyond the shores of England for the best man to carry on the saga of style. Zaheer Abbas walked into the large shoes as if they had been made to order for his exclusive use.

Zaheer drove like a dream, and the covers were his favourite route. Like Hammond, he liked to score huge hundreds. The similarities went further. It is perhaps not coincidental that both the batsmen had biographies written by David Foot.

In Zed, the book on Zaheer’s life, Foot underlines the likeness between the two legends. “As a psychological study (Zaheer is) complex in the same way that Wally Hammond was. Both saved their eloquence for the crease; both were withdrawn and defensive. Both engendered enormous respect and both opted for a privacy that did not come easily in a cricket dressing room.”

However, it must not be concluded that Zaheer had the same melancholy strain that dogged Hammond throughout his life. Indeed, Foot makes it perfectly clear after the above quoted paragraph: “There, I would suggest, the comparison ends. Hammond could be surly and cruelly dismissive. Zed’s personality is altogether sweeter.”

The first taste of England

The Gloucestershire men did not have to travel far or depend on heresy to discover the oodles of talent that Zaheer brought to the table.

The young man arrived in England in 1971, a member of the Pakistan side under Intikhab Alam. At that time it was his glasses that made more of an impression rather than his reputation. He had only one Test under his belt, a tepid affair in Karachi against New Zealand a year and a half earlier, and he had not really blazed away on debut.

There were some experts who were rather sceptical about his inclusion. His backlift was high, extremely high. Whereas it lent supreme visual delight to the strokes as his willow traced the full arc to the follow-through, such technique was supposedly suspect against the seaming ball.

Yet, right from setting foot in England, Zaheer demonstrated a talent and flair that marked him out as a batsman of rare class and pedigree. Worcestershire were the first opponents Pakistan came across, and Zaheer started with an impressive hundred. Consistent scores followed in May, including a hundred against Kent and a quick unbeaten 58 as Pakistan geared for declaration against Gloucestershire — the first time the County management saw him. The conditions had been mastered, and no bowling seemed to trouble him. Yet, there remained the little thing of proving himself at the highest level.

The opportunity arrived in the first Test of the series, at Birmingham. Coasting on consistent scores, Zaheer appeared in his second ever Test match. Another pimply faced young man made his debut for Pakistan in that Test — a tearaway pace bowler called Imran Khan.

The circumstances as Zaheer walked out to bat could not have been less auspicious. Off the third ball of the Test, bowled by Allan Ward, Aftab Gul was struck on the head and had to retire to get his wound stitched. Zaheer, eyes quietly confident under those imposing glasses, walked out with just one run on the board. And he proceeded to give an exhibition of artistry that the Edgbaston crowd would narrate with misty eyes to their grandchildren.

The drives were sublime right from the beginning, and many of them played delightfully through the on-side. In fact, in spite of being soon acknowledged for his greatness through cover and mid-off, this particular innings was etched with superb placements on the other side of the wicket. So complete was his composure that when he walked off unbeaten on 159 at the end of the first day, every run scoring record across time and space seemed to be under threat. And by the next afternoon, all the portents seemed to be coming true. Zaheer moved from milestone to milestone, without any apparent inclination towards being dismissed. At 261, he became the first batsman to complete 1,000 runs in that English season. It was ominous. From 1973 to 1982, Zaheer would score more than 1,000 — sometimes many many more — every season.

It was perhaps sheer fatigue which led him to sweep Ray Illingworth down the throat of Brian Luckhurst when on 274. However, he later dismissed claims of exhaustion, saying that he had been thinking of the world record of 365 then held by Garry Sobers. In any case, his reputation was made and sealed with a stamp of class.

In the next match at Lord’s, he top scored with a gritty 40 in precarious conditions for batting, with heavy clouds in the sky and plenty of rain in the air. In the thrilling third Test at Headingley, the only match that saw a result, Zaheer held the first innings together with a polished 72, enabling Pakistan take a 34 run lead. But, when they chased 231 for a win in the fourth innings, he was dismissed first ball, caught at short-leg off Illingworth. Pakistan lost by 25 runs.

Despite the loss, young Zaheer was the most sought after foreign player of the summer, with several counties waving attractive contracts. He threw in his lot with Gloucestershire. The committee members started following him around after the double ton in Birmingham. They came over to Bradford to watch him against Yorkshire. And then they traced his steps to Oxford where he played the University men. The deal, a modest one with a basic salary of £1,750, was signed in that city of dreaming spires.

It was an watershed moment for the batsman. Before the tour he had promised himself that he would give up the game if he did not do well. In the 206 matches he would play for Gloucestershire over the next dozen years, Zaheer would amass 16,083 runs at 49.79 with 49 hundreds.

The success in England also opened other doors. In 1971-72, Zaheer went down to Australia to turn out for the Rest of the World led by Garry Sobers. He was also named one of the Wisden Cricketers of the Year in 1972

Of partitions and escape routes

Syed Zaheer Abbas Kirmani was born at Sialkot, in an environment of sports and games. Father Ghulam Shabbir was an athlete and stationed in Bikaner where he was engaged in locust control for plants. When Zaheer was conceived during the turbulent times of Partition, Ghulam sent wife Kaneez Fatima to Sialkot for safety.

Shabbir himself tried to follow his family through Bhatinda, but was blocked by riots that raged along the way. So he traced the path that Mughal Emperor Humayun had taken after being defeated by Sher Shah, and made his journey through Tharparkar desert and Umarkot. The father reached Karachi five days after Independence, 27 days after the birth of Zaheer. He finally managed to see his new-born child in September.

After a couple of years in a remote outpost called Turbat in Mekran desert, Ghulam moved to Karachi. Zaheer played his first game in the improvised pitch in front of the government quarters where the family lived. Before he turned seven, Zaheer was playing in the village matches, sometimes crossing the river to get to the ground, most often carried on the shoulder of older players. His younger brothers followed his footsteps into the world of sports. Of the six, four became cricketers and two moved to hockey.

Zaheer’s ability was recognised at an early age, but as was to be the story of his Test career, his path to the top was often erratic. After his stints at the Government School, Islamia College and Karachi University, Zaheer continued to play for Park Crescent in the Karachi League. Soon, he was employed by Pakistan International Airways (PIA), where his main task was to play cricket and hold down a position in the sales department. The fascination for big runs did not take long to make itself manifest. Zaheer was included in the Karachi side, and his maiden century amounted to 197 against East Pakistan in the Quaid-e-Azam Trophy in 1967.

Tall scores continued to flow and he was sent on a brief tour of Ireland with PIA. He had a reasonably successful time and the experience stood him in good stead during the England tour of 1971.

Yet, his first big season was full of disappointments. He did not fire on his debut against New Zealand at Karachi in October 1969. He was not considered for the home Tests against England. The proposed tour match in which he was scheduled to appear against Colin Cowdrey’s men was washed out by rain. The scheduled visit to England with the Under-25 team in the summer of 1970 was cancelled because of the raging problems surrounding the South African visit to Ole Blighty.

However, when the next season came along, Zaheer equalled Hanif Mohammad’s record with 5 hundreds in the season. This included 202 against Karachi Blues, much of it against the bowling of Intikhab Alam. His place in the Pakistan side for the 1971 tour to England was sealed.

An inconsistent tale

Zaheer continued to pile runs in England, for a decade, either for Pakistan or Gloucestershire. However, his success in the Test world was not as uniform.

After his England success, he was ordinary in Australia and miserable in New Zealand. He had a torrid time when the same England bowling arrived in Pakistan in 1973. Plenty of runs were plundered on the county fields in the summer and the in the Pakistan domestic circuit in the winter, but the Test returns dwindled drastically.

Even when he toured England again in 1974, the runs refused to come at first. His batting average, 70.83 at the end of the 1971 series, had plummeted to 31.43 by the end of the second Test. And suddenly all the un-scored runs gushed forth in another enormous innings of 240 at The Oval in the third Test. He batted for 545 minutes, one minute longer than his Edgbaston epic. It was a tall-scoring draw, but Zaheer had re-established his class, and reaffirmed penchant for gargantuan scores. The nickname Asian Bradman was born.

But, yet again, the subsequent series were almost abysmal. Five Tests were played over a year and a half, all at home, three against New Zealand and two against West Indies. In nine innings, Zaheer scratched around for a meagre 131 runs with a highest of 33. Surprisingly, this was interspersed by the summer of 1976, when as many as 2,554 happy runs flowed from his bat under the English sun, with his willow being raised to mark 11 centuries. His sublime greatness was never in question, especially in England, but somehow, other than a few innings, the results in Tests were negative.

Runs at home and away

Zaheer started setting things right in Australia in 1976-77, against the formidable attack of Dennis Lillee and Jeff Thomson. He was instrumental in saving the first Test at Adelaide by the skin of the teeth, with resolute yet pleasing knocks of 85 and 101. This was his first century in Tests, apart from the 2 double-hundreds.

Australia won by a big margin in Melbourne, but Zaheer took the fight to the hosts with 90 and 58. He failed in the third Test at Sydney as a brilliant Imran Khan squared the series for Pakistan with 12 wickets. However, the series did establish something that the world knew but till then had scant evidence of — that he was good enough to score runs in countries other than England.

The talent was palpable, and soon attracted the attention of Kerry Packer’s recruiting officers. Zaheer played two seasons for World XI with moderate success, scooping up pearls of experience. However, it led him to miss two series against England.

It was when India resumed cricketing ties with Pakistan in 1977-78 that Zaheer hit his first purple patch at home. As Pakistan romped to a 2-0 victory, he skipped on his quick feet and murdered the venerable band of great Indian spinners.

Zaheer started the series amassing 176 and 96 in the draw at Faisalabad, thereby notching up his first hundred in Pakistan. He followed it up with an unbeaten 235 in the first innings at Lahore. When the home team came out chasing 126 runs in quick time, Zaheer, with his loads of experience of limited-overs cricket in England, scored an important unbeaten 34 to take them home.

However, having scored another hundred in New Zealand in early 1979, Zaheer once again fell prey to his sinusoidal career graph. He failed miserably in Australia, in the series that followed in India and when West Indies and Australia visited in 1979-80 and 1980-81. And all the while he piled on runs for Gloucestershire. In 1982, for the first time he played a Test series in England without remarkable success.

By the end of the England tour, Zaheer’s fluctuating performances were once again having a telling effect on his statistics. While his class was never in question, his average, which had peaked towards the mid-40s with the 1977-78 series of India, now dipped under 40. At this stage of his career, he had played 49 Tests and scored 3,154 runs at 39.92 with 7 hundreds, three of them double. His numbers were full of evidences of brief supreme periods of run-making followed by incomprehensible phases of mediocrity. The greatness of his blade seemed constrained by these severe bouts of inconsistency.

International batsman of the Year Challenge, 1979. From left: Gordon Greenidge, Zaheer Abbas, Asif Iqbal, Barry Richards, Ian Chappell, David Gower, Graham Gooch, Clive Lloyd © Getty Images

The form of his life

And this is when he hit the form of his life. In the next 22 Tests he hammered 1,787 runs at 74.45, and transformed his status from the brink of greatness to one of the best in the world. During this phase, the drives remained as effortlessly elegant as ever, but every stroke seemed to be enhanced by some generous portions of extra time, allotted only to his genius.

The first to suffer were the visiting Australians, beguiled by Abdul Qadir’s spin magic and slaughtered by the metronomic massacre meted out by Zaheer. In 3 innings, 91, 126 and 52 flashed from his blade.

And when India visited, he stroked his way to 215 in the first Test at Lahore, his much celebrated hundredth First-Class century. He became the 20th batsman to get to the milestone, the first man to have achieved the feat from the subcontinent, the first non-Englishman apart from Don Bradman and Glenn Turner. He is still the only Asian batsman to have scored over 100 centuries in First-Class cricket.

Zaheer celebrated with 186 at Karachi and 168 at Faisalabad. Pakistan won the series 3-0 and the bespectacled maestro plundered 650 runs at 130. In the One Day Internationals contested during the tour, he plundered 3 hundreds in succession at Multan, Lahore and Karachi. In the end several Indian players started to exclaim: “Zaheer, ab bas” (stop now, Zaheer).

Pakistan reached the semi-final of the Prudential World Cup in 1983, and Zaheer was in sublime form in his favourite English conditions. In the seven games, he scored 313 runs at 62.60.

At the helm

With Imran Khan succumbing to his infamous shin injury, Zaheer was made captain of Pakistan for the tour of India in late 1983. He led the team in 14 Tests between late 1983 and late 1984, and did a decent enough job, winning 3, losing just 1 and drawing the rest.

However, he did court controversy in his very first Test as skipper, at Bangalore, refusing to go through the last few mandatory overs as a meaningless stalemate was played out, a period that Sunil Gavaskar was utilising it to reach his 28th Test century. At one stage, Zaheer had led his team out of the ground with Gavaskar on 87, and made it back only when umpire Madhav Gothoskar warned him that the match would be awarded to India.

As captain initially his willow remained productive, with the highlight being another huge 168 against India at Lahore. That was during the 1984 series, called off mid-way due to the assassination of the Indian Prime Minister Mrs Indira Gandhi. It was his last serious success with the bat.

The unfortunate last days

By the time New Zealanders visited in late 1984, it was evident that age was catching up with the master batsman. After this prolonged flood of high scores, the runs dried up yet again and were reduced to a painful trickle. Even the consistency for Gloucestershire had come to an end. When the team flew to New Zealand in early 1985, the 37-year-old had handed the captaincy over to Javed Miandad.

Except for that one series against Australia with Dennis Lillee and Jeff Thomson at their prime, Zaheer had never quite fancied scorching pace. His record had remained mediocre against the West Indian pace battery. There is the story Jeff Dujon recounted about an innings for World XI, when several bouncers from Andy Roberts had made him distinctly uncomfortable and had led to his speedy departure. Colin Croft had struck him on the head in Karachi in 1980-81 and Thomson had hit him during the match against Queensland in 1981-82.

Now, the pace of Richard Hadlee and Lance Cairns seemed a little too hot to handle at the advanced age. After scores of 6, 12, 6 and 0 in 4 matches, it was evident that his time was up.

He played 2 more Tests the next season, against Sri Lanka at home, batting just once and scoring 4 measly runs. The great career fizzled out, maintaining that curious sequence of highs and lows that characterised it all through. He opted out of the last Test at Karachi, and departed without a proper farewell, indirectly blaming senior players like Imran for his inglorious exit.

Career in retrospect

Zaheer ended with 5,062 runs from 79 Tests at 44.79 with 12 hundreds. His collection of runs stood as a record aggregate for Pakistan until Javed Miandad went past him. What is surprising in his career is the remarkable difference between his home and away figures.

Zaheer Abbas in Tests

The contrast is even starker if one considers the Tests played in England as a separate category. His record in the other countries comes across as extremely ordinary.

Zaheer Abbas in Tests

Considering players of his stature, ranks with Dilip Vengsarkar, Desmond Haynes and Denis Compton as batsmen with the greatest home-away difference in their careers.

Another defining facet of his career are the ways in which great feats with the bat were interspersed by utter failures. Except for a supreme period in the early 80s, his career kept going through fluctuations of sublime highs and miserable lows.

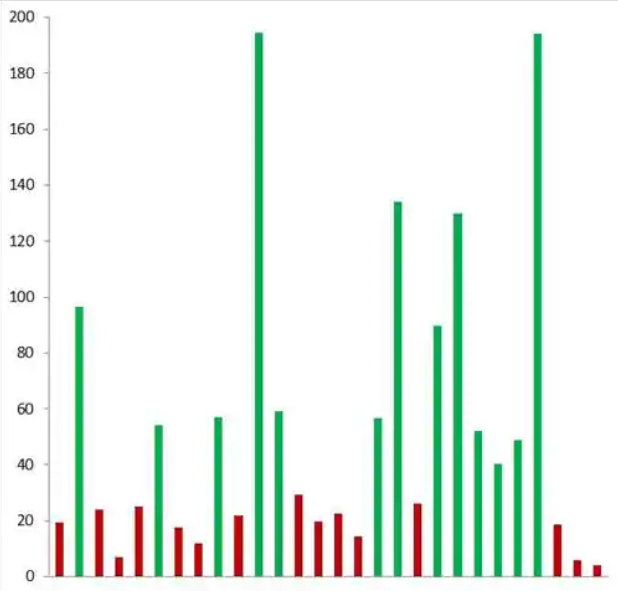

Zaheer Abbas: Averages for each Test series — Sublime highs and Miserable Lows

His figures, however, are extremely impressive in ODIs, especially given the era he played in. He appeared in just 62 matches, but his 2,572 runs came at 47.62 with 7 hundreds, at a strike rate of 84.80 — which is more than respectable even by current day standards.

The style and the man

Throughout his career Zaheer remained graceful and almost lyrical in his strokeplay. The gift of timing could be both seen and heard as he caressed the balls off the front foot through the off-side.

Zaheer was also infamous for going off the field when the opposition batted. Not quite fond of fielding, he nevertheless had a safe pair of hands. Once, while diving full length to catch Gary Gilmour at gully in a county game, he broke his glasses, bruised his nose and ended up with blood on his flannels. Yet, he wore the same glasses till the end of his career, with the repair marks clearly visible on the frame.

Although not one for athletic activity on the cricket field, Zaheer nevertheless ran hard while at the wicket. There is the well-known story of his partnership with David Shepherd, which saw the rotund chubby umpire-to-be flat on the ground after a spate of quickly run singles and twos. But, according to Foot, he was not an ideal man to run with. “His all-embracing love of scoring runs leaves him open to criticism that he can be a somewhat selfish team-man…. A batting partner, unfortunately run out, has been known to throw a momentary look of protest down the length of the pitch.”

Off the field he remained low key and modest, unusually so given the degree of glamour associated with cricket in his country.

According to biographer Foot, he avoided parties, sponsors’ tents and sycophantic supporters. He was quiet, easy going, gentle yet stubborn, and at times resentful.

While his driving on the field was legendary, the same behind the steering was strikingly scary. Frank Wisleton, a former Chairman of Gloucestershire, once remarked, “He is the worst that I’ve ever known. Once he took me from the team hotel near Marble Arch to the Oval. I’ve never been so terrified in my life. He drove very slowly — but his head was everywhere.” There are also stories of Sadiq Mohammad and Zaheer losing their way while driving to a Sunday League game for the county.

The Pakistan dressing room is not really the ideal place for a player to tarry for a decade and a half without undergoing unpleasant interactions. In his biography, the first chapter is titled ‘The Unhappiest Tour’, and it talks about the 1981-82 visit to Australia when captain Miandad supposedly resorted to behaviour that can be categorised as snubbing and insulting.

Yet, Zaheer did enjoy one a fantastic career, much like his numbers an amalgam of rough and the smooth. For a while in the 1980s he was indeed one of the best batsmen in the world. After his playing days, Zaheer has played the role of the manager of the Pakistan side. It was during his stint that the infamous Oval Test of 2006 took place. The Pakistan team refused to take the field after being accused of ball tampering and conceded the match. While some of the blame obviously needs to be shouldered by Darrell Hair and his obstinacy, the incident was strikingly similar to Zaheer’s first Test as captain in Bangalore, 1984, only with more extreme results.

He has put on the hat of a cricket expert now, and often makes appearances in programmes that leap over the rather crude border between cricket and reality show.

However, Zaheer will be forever be remembered as one of the greatest batsmen produced by the sub-continent, and certainly one of the most elegant and graceful stroke-makers of all time, whose appetite for runs became legendary enough to equate him with Don Bradman.