by Arunabha Sengupta

South Africa, 1913-14. SF Barnes, perhaps the greatest bowler of all time, picked up 104 wickets during the tour at 10.74. He did not play the fifth Test because of problems with the management—they would not pay for his wife’s accommodation. Nevertheless, Barnes captured 49 in the other four, at 10.93 apiece.It remains a record after a century and more.

Only one batsman made sense of him—the young South African master Herbie Taylor. “Taylor was very quick on his feet, and got to the ball either forward or stepping over the off-side to pull,” wicketkeeper Herbert Strudwick recalled.

It was one of those duels that make cricket the game of romance. Taylor scored 824 runs against MCC during the encounters that season at an average of 68.67. In the Tests he made 508 runs at 50.80. Barnes got him on five occasions.

Louis Duffus, that sterling South African cricket writer with his lilting turn of phrase, wrote beautifully and convincingly about the face-off. And with Cardusian clairvoyance, he created an anecdote that has lived on to this day among those who are interested in the pre-history of the game.

Against Natal, just before the fourth Test, the only match MCC lost on the tour. By four wickets. Barnes 5 for 44 and 2 for 70. Taylor 91 out of 235, 100 out of 216/6. In the second innings Taylor was joined at the wicket by Dave Nourse.

This is how the Duffus account runs in Cricketers of the Veld: “As Dave Nourse walked out to the pitch, the younger man murmured to himself, ‘If one of us goes, it’s all over.’ And indeed the collapse seemed inevitable for, when Nourse faced Barnes, he was patently confused by the vicious spin, the unvarying length and devil of the English bowler’s attack … Walking up the pitch between overs he conferred anxiously with the colleague who was eleven years his junior. “’I can’t get the hang of Barnes,’ he said. ‘He’ll get me.’ His partner set his mouth grimly, ‘All right,’ he replied. ‘I’ll play Barnes.’”

Having somehow managed to divine remarks made to oneself and the conversation between two batsmen in the middle, Duffus continues to describe how Taylor shielded Nourse that day, against the greatest of bowlers.

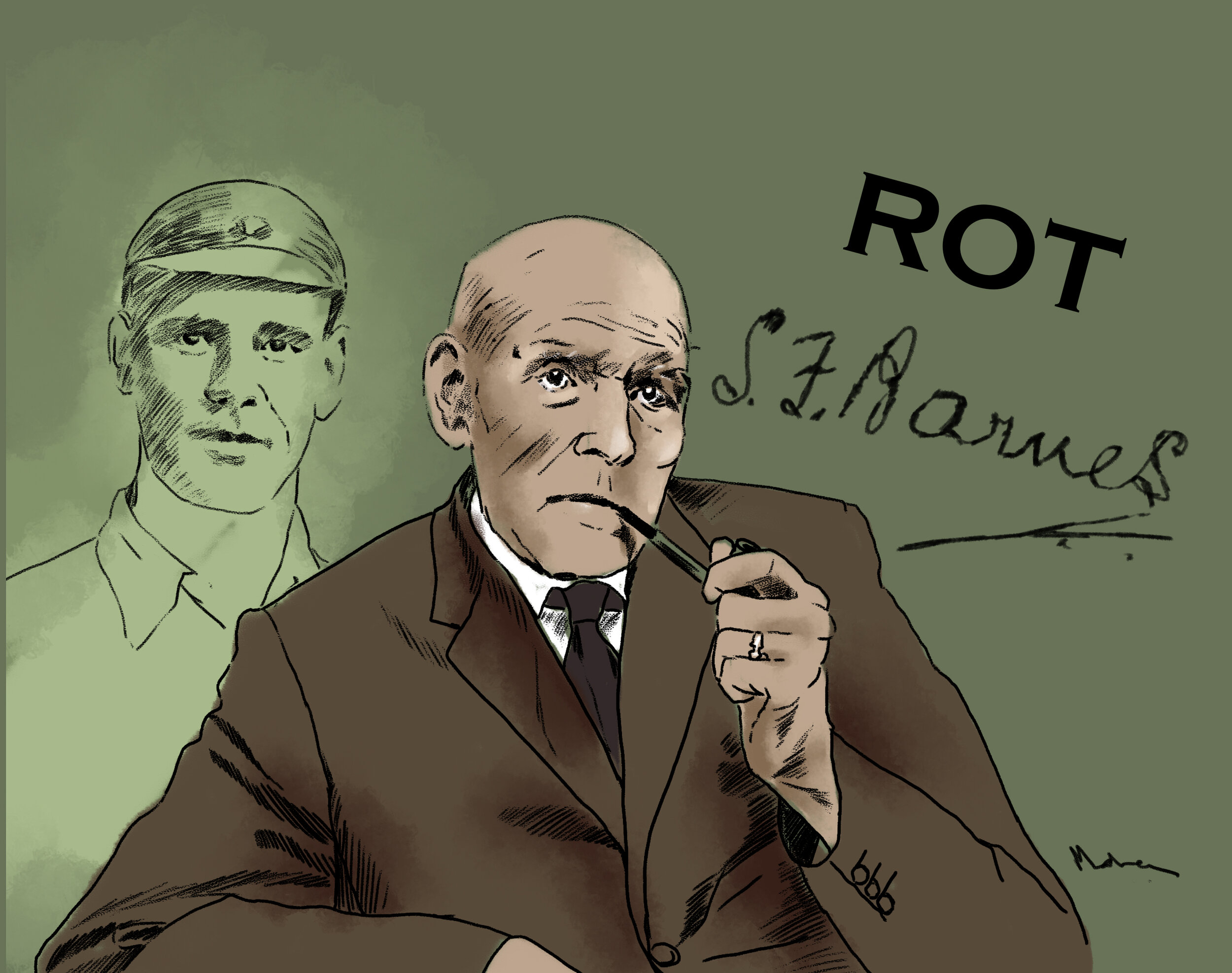

“For Barnes the position was tantalising beyond words. Here was a batsman ostensibly ripe for plucking and repeatedly being snatched out of reach. At the start of each new over, not Nourse but Taylor, with an air of aplomb, faced him at the other end of the pitch. Finally, in a fit of pique, Barnes threw the ball down on the ground and declined to bowl. ‘It’s Taylor Taylor Taylor all the time,’ he exclaimed.” There was also a cartoon by Leyden of Barnes and his exasperation that accompanied the piece. According to Duffus, Barnes left the field at this juncture, without informing the captain.

Much more prosaic, and hence less recounted, is the version of Leslie Duckworth, the biographer of Barnes, the tireless chronicler of Warwickshire cricket. According to Duckworth, Barnes says that Taylor was distinctly lucky because he was caught at the wicket more than once and the umpiring was hardly ideal. At one stage none of the English players would even appeal, they all sat down in protest. On reading Duffus’s account, Duckworth wrote to Taylor for his recollections.

In response he received a long letter from the South African maestro about how he mastered Barnes. It was obviously a grand gesture on Taylor’s part to give such a detailed account, but there are flaws in his story. Nourse was caught off Woolley and not Rhodes as he claimed. Taylor himself was caught in the slips, by Woolley, but not off Barnes but Hearne. The scores recounted are also somewhat confused. Memory is always misleading.

When Duckworth sent the same query to Barnes the response left fewer opportunities for error. The answer was inimitably terse and inscribed in his characteristic copperplate, “Rot. No such thing. It took Taylor all his time to protect himself and Nourse was too good a bat to need this.”

When asked, Rhodes, Woolley and Tiger Smith, they all confessed to having no recollection of Barnes throwing the ball down and walking off the field. Neither was there any such account in The Times also made no reference to Barnes displaying ill temper or leaving the field of play. Duckworth approached Natal Mercury journalist CO Medworth who went through MW Luckin’s book about the history of South African cricket and then the three-column report of the match he found in his newspaper files. Medworth concluded, “In face of this evidence … it is a good story, but does not seem to be justified by facts.”

As a footnote, in the winter of 2014 I was in Epsom, Surrey, having lunch with the South African born cricket bookseller John McKenzie. A devoted collector of cricket books since his early youth, McKenzie had known and read Duffus and had been similarly intrigued by the story as a teenager.

Like Duckworth, McKenzie had sent a couple of letters, one addressed to Taylor, the other to Barnes, asking for their corroboration of the events as described by Duffus.

And he had received two responses.

The one from Taylor had been long, detailed, much like the letter he had sent to Duckworth.

Barnes, still engaged in copying legal documents for the Staffordshire County Council, sent his reply in his beautiful copperplate handwriting. It read: “Rot.”

SF Barnes, or as commentators painstakingly read out the statistical graphics from television screens nowadays—‘Ess Eff Barnes’, was born on April 19, 1873. He captured 189 Test wickets at 16.43 in 27 Tests.

His approach to bowling is summed up in what he once told Hugh Tayfield: “Don’t take any notice of anything anybody ever tells you.”

Illustration: Maha