by Arunabha Sengupta

Oval, 1971. England started confidently, cushioned on a lead of 71.

And then he struck, although not really in the manner or direction expected. Brian Luckhurst drove hard. The leg-spinner got his hand to it and it was deflected on to the stumps. John Jameson was out of his crease.

A few minutes later, as he ran in to bowl to John Edrich, a teammate called out “Mill Reef.” The name of the Derby winner that summer. And the code name for the faster delivery of Bhagwath Chandrasekhar. The ball was ripped through. Edrich’s bat was still in the air when it hit the stumps. The next delivery was gobbled up by Eknath Solkar at short leg.

Bella, the elephant from Chessington Zoo, plodded around the outfield during lunch. And after resumption, Chandra kept striking. Six for 38 from 18 overs. England all out for 101.

“On a pitch which gave him little if any assistance Chandra had vindicated a vanishing breed of bowling in a fashion which can only be described as astonishing,” gushed Playfair Cricket Monthly.

India made heavy weather of the 173-run target, but got through in the end. The series was theirs, for the first time in England.

Chandra won India many more Test matches. Against Australians in the Brabourne Stadium in 1964-65 was the first. The two Tests in Australia in 1977-78 were the last. In between there were The Oval, Auckland, Port of Spain, twice at the Eden Gardens.

Leveraging on his deformity, became a weapon of destruction—more than any Indian bowler till the advent of Anil Kumble.

As a five-year-old, Chandra suffered an attack of poliomyelitis. After three months in the hospital, it was discovered that his right arm would remain withered and emaciated.

The world of sports does not lack examples of champion athletes overcoming physical challenges. Doris Hart won the Wimbledon singles champion after an infection in the knees as a child which almost crippled her. Wilma Rudolph contracted infantile paralysis at the age of 4 and went on to win three sprint gold medals at the 1960 Rome Olympics. Bethany Hamilton emerged as a champion surfer after losing an arm to a shark attack. In cricket, Len Hutton enjoyed years of sustained brilliance after having his arm shortened due to a gym accident during the Second World War. Denis Compton returned to Test cricket after having his knee cap removed. Fred Titmus bowled for England after losing three toes in a boat accident. Bert Ironmonger and Pat Cummins lost parts of their fingers in their bowling arms, Azeem Hafeez several fingers of his non-bowling arm.

Yet, Chandrasekhar was unique. He was perhaps the only one to turn his deformity into his lethal weapon. (Perhaps Muralitharan can be counted as another) The thinness of his arm resulted in unique flexibility, helping him produce extra bite in his top-spinner. For most of his career, he sent down top-spinners and googlies, at close to medium pace, often unplayable off the pitch. Often he himself was not quite sure what the delivery would do after pitching.

He was perhaps the best among the spin quartet of India, definitely the one who won most matches, and definitely who spoke the least about his deeds. He never turned a self-propagandist or mythologist like some of his comrades.

Chandra was almost as popular for his match-turning bowling spells as for his remarkable ineptitude with the bat. He retired with the then world record of 24 ducks and a batting average of 4.67. His collection of Test runs — 167 — remains 75 less than his number of wickets! The Gray-Nicolls bat with a scooped centre, presented to him during the Australian tour of 1977-78 in the ‘honour’ of his four ducks in the Tests, remains a rather curious memento. He accepted it with his characteristic affability.

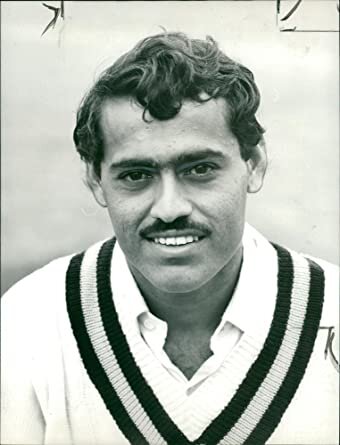

Bhagwath Chandrasekhar was born on 17 May 1945.