by Arunabha Sengupta

He was a scrapper. In cricketing terms, he was a Yorkshireman and a half.

4522 runs as an opening batsman at 61.10.

Ahead of the rest of the field across the history of Test cricket by more than five runs per innings.

The one innings he played as a non-opener was on a sticky at Adelaide, when the batting order was shuffled, and he came in at No 6 and scored 33. Even in that innings, he added 90 with Jack Hobbs.

Together they added 3249 runs at 87.81. The best partnership in the game, ever.

Len Hutton followed them a decade later. Together the triumvirate of Hobbs, Sutcliffe and Hutton stand head and shoulders above any other opening batsman … ever. (Chorus of ignorant, parochial screeches notwithstanding.)

Yet, Sutcliffe is seldom spoken of when great, and often not so great, opening batsmen are recalled. Precious little is documented in terms of eulogies to his craft of batting.

Wisden does state that his off-drive wore a silk hat – but that was in his obituary, when noble cricketers departing for the happy grounds of the other world carry away characteristics that seldom graced them in their active days.

Herbert Sutcliffe was not a pretty batsman to watch.

He grasped the bat as if he intended to chop wood with the south west corner, and met the ball with less than the full width when he played forward. Sutcliffe’s grip forced his bat to face cover point and the inside edge towards mid-on. Ray Robinson observed that Sutcliffe’s bat reminded him of a twisted front tooth.

He used to lunge while playing off the front foot – giving the indication that at least to leg-spinners on fast wickets, he thrust his bat and left the rest to luck. And Australia, the land full of fast wickets and legendary leg-spinners in his days, waited for him to succumb as Arthur Mailey, Bill O’Reilly and Clarrie Grimmett beat him time and again outside the off stump.

The country would still be waiting when somehow, hours later, Sutcliffe would raise his bat and acknowledge the surprised applause on reaching yet another hundred.

In Australia he did so 6 times, scoring 1,529 runs at 63.

For all the Wisden eloquence about his drive, he often scored very few in the ‘V’. His most productive off-side stroke was the jab past point for a single or two. The most inviting half-volleys often escaped without a drive. At The Oval in 1930 he scored 161, with only 33 coming between point and long on. At Brisbane in 1933, he batted close to 4 hours without a boundary between second slip and square-leg.

No, he was not a pretty batsman; just one of the greatest of them all … who ended with better returns than Jack Hobbs, Wally Hammond, Frank Woolley and the rest of them.

No wonder Neville Cardus, that doyen of cricket writers and flamboyantly fraudulent chronicler, hardly ever wrote a word about Sutcliffe while weaving his intricate tapestry of metaphors around his celebrated opening partner Hobbs.

Cardus wrote about Hobbs batting — at the wicket, at the nets, in the prime of his life and as an aged master. But when he wrote about the great man’s illustrious partner, it was mostly as an afterthought.

Cardus of course did not like Sutcliffe’s penchant for Saville Row suits and expensive hats. That, to this eternal snob, was a professional cricketer reaching above his station. Well, but then that is Cardus and his mix of supercilious nonsense.

But it does show much disservice non-objective cricket chronicling can do to the game and its conscious memory.

The problem is that the establishment also did not quite enjoy Sutcliffe’s assertions that as professional he could become captain. In 1934, with Sutcliffe and Hammond striding into the ground like a pair of cricketing colossi, it was six-Test old Cyril Walters who led England. The class system of English cricket also redefined the ridiculous.

If Sutcliffe felt slighted with the attention of poetic eloquence concentrated on Hobbs, Hammond and Woolley, he seldom let it affect him. He went about batting in his characteristic manner, frustrating bowlers and often the crowd, but managing to score tons of runs.

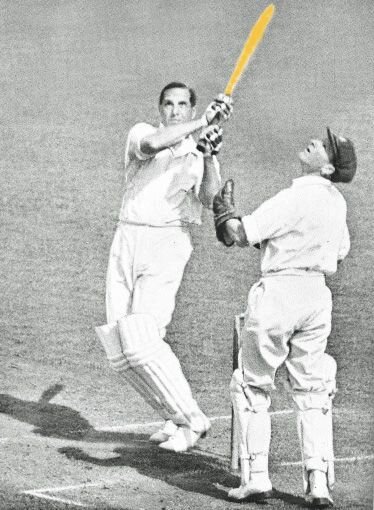

His movements at the wicket were endearing in their own right, patting down undecipherable unevenness on the pitch, picking up and removing the minute blades of grass, drawing himself up to his full five feet nine inches and surveying the field with magnificent aplomb, his cap-less head glossy with grease, the sleekest hair-do in Test cricket.

Although he seldom ventured into adventurous offside strokes, he left balls outside the off-stump with magnificent flourish. And he let himself go when hooking short balls. If the ancient scorecards show a six against his name, a reasonable wager is that the stroke was a hook. Jack Gregory, Tim Wall and the rest of them bounced him often in the hope of getting him caught at the leg boundary, but it happened just four times in his entire career.

It was on bad, sticky and unplayable tracks that Sutcliffe proved to be a phenomenon. His greatest innings came in 1926 at The Oval. It was the occasion when he and Hobbs added 172 on an unplayable mud-pudding. Hobbs got 100, Sutcliffe 161.

Sutcliffe’s collaboration at the top of the order with Hobbs has remained unmatched. They patted balls gently, rolled them barely clear of the pitch and singles were stolen under the noses of fieldsmen, although neither seemed to hurry between wickets. Occasionally they did say “Yes”, “No” or “Wait”, but most often fielders had no clue about their intentions. Many attributed their understanding to telepathy or at least lip-reading.

Sutcliffe’s approach to the game can be summed up with this characterising anecdote. When congratulated for saving England with yet another stubborn rearguard innings, Sutcliffe once responded, “I love a dog-fight.”

A self-made batsman who towered over most of the celebrated princes of the game.

Herbert Sutcliffe was born on 24 Nov 1894.