On March 22, 1992, an edge of the seat thriller of a World Cup semi-final was ruined by 12 minutes of rain and a ridiculous application of the rules. Arunabha Sengupta looks back on the match which is one of the most embarrassing moments of cricket history.

It took 12 minutes of rain for a superb semi-final encounter to go down as the most ridiculous farce enacted in any sporting theatre.

RC Robertson Glasgow, had he lived to see the day, could have modified the title of his sparkling book on cricket memories from, “Rain Stops Play” to “Rain Stops Minds”.

Indeed, the events that unfolded after the downpour started, and more so after it stopped, defied logic and went far beyond the realms of rationality, even when viewed with the television- linked contractual aspects in the backdrop. A match that had gone down to the wire ended with a ridiculous final delivery that left the players bemused, administrators shame faced and the crowd seething. South Africa, who, within a year of coming out of their seclusion, had entered the imagination of the cricketing world, suffered the most terrible of heartbreaks.

England, buoyed by a fluent 83 by Graeme Hick – who was caught off a no ball before scoring – set a rather steep target of 253 off 45 overs. Hampered by an injury to their star batsman of the tournament, Peter Kirsten, South Africa rallied through some healthy contributions by Andrew Hudson, Adrian Kuiper and Jonty Rhodes. When big Brian McMillan was joined at the wicket by wicket keeper Dave Richardson, 47 were required from the final 31 balls.

With the ground lit up by floodlights, the sombre skies in the background and a capacity Sydney crowd on the edge of their seats, the experienced duo mixed excellent common sense with some neat placements to notch 25 off 18. As McMillan got ready to face the final ball of the 43rd over bowled by Chris Lewis, the skies opened up.

Aware of the complications of the rain-rule, which deducted the runs from the most economical overs of the first innings from the target, the batsmen stayed on in the ground, but when the umpires offered the option, Graham Gooch, citing slippery ground conditions, led his players off the field.

The rain stopped after just 12 minutes, and with the lights blazing down on the ground, and a reserve day available for the taking, perhaps no player or spectator assumed anything but the completion of the remaining 13 balls. However, even if the rain gods had relented, the money gods could not be displaced from the throne of unreason. Channel Nine had specific guidelines about the timings of the match, and to adhere to the schedule and prevent financial complications, the rules were followed by the letter and, beaten to the post by corporate callousness, common sense left the ground unseen.

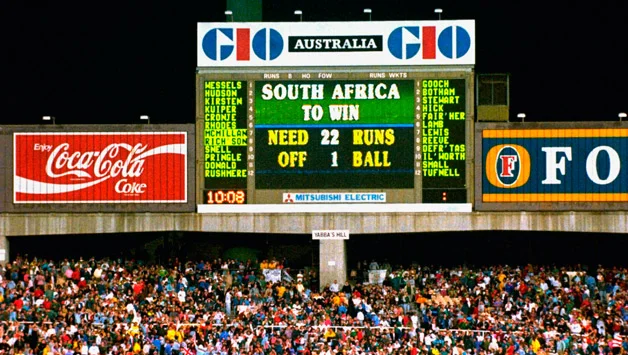

The scoreboard displays the absurdity of the rain-rule © Getty Images

At first, the confused crowd were greeted with the display on the scoreboard announcing that South Africa needed 22 runs in 7 balls. It seemed one over had been deducted, and the task was difficult, but perhaps not impossible.

However, moments later, it was changed to 22 off one ball (although academically the correct target should have been 21 from one). Meyrick Pringle’s excellent couple of overs which had yielded just one run had been deducted from the target.

A shake of head along with a resigned chuckle from Peter Kirsten in the South African dressing room summed up the situation. McMillan somehow forced himself to resume his stance and pat Lewis for a single off the farcical last ball, and set off for the pavilion with a face darker than the Sydney skies that had threatened all day. England won by 19 runs, aided by the most clerical implementation of rules.

John Woodcock summed it up in The Cricketer, “South Africa’s chances of reaching the final floundered on a rule which no-one had bothered to think through. For so important an event to be reduced at times to a lottery must have been a source of great embarrassment to the organisers, though to the best of my knowledge they came nowhere near to admitting it. It is difficult to avoid the impression that the Australian Cricket Board are obliged to defer to television, by which I mean to Mr Packer’s Channel Nine and all their delirious ways.”

Kepler Wessels sportingly led his team in a farewell jog around the field, but the question lingered – could this have been the victory lap?