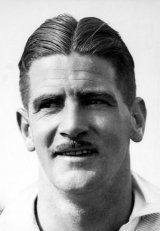

Chuck Fleetwood-Smith, born March 30, 1908, was the first left-arm wrist spinner of Australia who made it to the Test side. A maverick genius if there ever was one, he did not do justice to even a fraction of his talent. Arunabha Sengupta recalls the career and the troubled life of this Test star who later became a vagrant.

Magic at Adelaide

Adelaide 1937. The Ashes series hung on the proverbial knife’s edge. Gubby Allen’s Englishmen had led 2-0 after the first two Tests, Don Bradman’s captaincy days getting off to a nightmarish start. And then the legend had turned things around with the incredible 270 at Melbourne in the second innings.

Now, with the series 2-1 in favour of England, another double hundred by The Don set the visitors 392 to win. By stumps on the fifth day of the timeless fixture, England were 148 for three. The great Wally Hammond was unbeaten on 39. Along with him was the prolific Maurice Leyland. The wicket was still playing beautifully.

And the next morning, Bradman handed the ball to the maverick left-arm wrist spinner ‘Chuck’ Fleetwood-Smith. For good measure, the great man let his eccentric genius know that the match rested in his hands.

It worked like magic. Before Hammond had added to his score, Fleetwood-Smith ripped across a near perfect delivery. Drawing the Gloucestershire maestro out with its flight, it drifted away in the air, landed on the turf and zoomed back through the bat and pad to rattle the stumps. And with the retreating steps of Hammond, England’s final hope of winning the Test, and eventually the Ashes, also walked back.

Four years earlier, when the visiting England side had played Victoria in the tour match, Hammond had been instructed to attack the rookie chinaman bowler. The young spinner had been hammered and the England batsman had gone on to score 203. Clarrie Grimmett had not been played in the Bodyline series after the third Test. But, Hammond’s carnage had stopped the selectors from risking Fleetwood-Smith in the crucial matches in spite of the need of a spinner. All-rounders Ernie Bromley and Perker Lee had been given a Test apiece.

Now, as the rest of the English wickets fell away for 94 additional runs, Fleetwood-Smith ended with six for 110, in addition to the four for 129 in the first essay. This is how Neville Cardus wrote about the battle he won against Hammond that day:

“Australia would have lost at Adelaide but for Fleetwood-Smith. Chuck took four years to gain revenge. He was suddenly visited by genius. Moreover he sucked the sweet blood of vengeance against Hammond. A lovely ball lured Hammond forward, broke at the critical length, evaded the bat and bowled England’s pivot and main hope … This achievement set a crown on the most skilful artistic spin bowler of the day.”

Fellow spinner, the incomparable Bill O’Reilly, was also sufficiently impressed to acknowledge it as the best delivery he ever witnessed in a major cricket match.

And Bradman himself wrote in Farewell to Cricket, “If ever the result of a Test match can be said to have been decided by a single ball, this was the occasion.”

After the Australian triumph, thousands of spectators assembled in front of the pavilion and chanted Fleetwood-Smith’s name until he made an appearance.

Later Bradman wrote that at the moment of the dismissal, his thoughts had gone back to the words of the old Australian wicketkeeper Sammy Carter. In the northern summer of 1932, Arthur Mailey had arranged for a private tour of the United States and Canada for an Australian team that included Bradman, Stan McCabe and several other premier cricketers. Young Fleetwood-Smith had been one of the party and 54-year-old Carter had kept wickets. During that tour, the left-arm spinner had played 51 matches and captured 249 wickets at less than eight runs apiece. Carter had observed that he would have liked to keep to Fleetwood-Smith for Australia because would someday the lad win a Test match for the country. His prophecy had come true.

The previous Test match at Melbourne had seen Australia execute that incredible turnaround in the series. The erratic genius had played a vital part in that game as well.

He was one of the worst possible wielders of the willow, and proudly so. His famed boast was “If you can’t become the best batsman of the world, you might as well be the worst.” He followed the maxim right through his career. And yet, after England had been caught on a sticky wicket and dismissed for 76 in the first innings thereby ensuring a 124 run lead for Australia, the best batsman of the world himself had sought him out and asked him to put on the pads and open the innings. His partner would be O’Reilly, the one man who could give him an honest run for his money as the worst batsman of the team.

When an incredulous Fleetwood-Smith had asked about the reason why, Bradman had responded: “The only way you can get out on this wicket is by hitting a ball. You can’t hit the ball on a good wicket so you won’t be able to edge it on this.”

O’Reilly had spooned the first ball back to Bill Voce. However, Fleetwood-Smith, with a combination of fortune and pluck, had managed to survive till the close of play. With a crucial zero not out against his name at stumps, the Victorian had returned to the pavilion and informed Bradman that he ‘had the game by the throat.’ He had not yet managed to hit a ball.

The next morning Fleetwood-Smith fell to the first ball he hit. But, Bradman went on to compile that supreme 270, adding 346 with Jack Fingleton. Set 689 to win, England could manage 323, Fleetwood-Smith capturing five for 124.

The wayward genius

He was indeed a rare talent. An ambidextrous prodigy who could bowl with either arm as a young lad, he focused on the unusual art of left-arm wrist spin. And he grew into one of the most devastating but erratic bowlers of Australia.

According to Bradman, “At his top he would deceive anybody as to which way the ball would turn, and his great spin and nip off the pitch were most disconcerting. This necessarily brought inaccuracy in its train, and many a time he became the despair of his captain because of his loss of control.”

He spun the ball prodigiously, and it travelled with an audible buzz towards the batsman. His wrists and fingers had been conditioned by squeezing a squash ball for years, and imparted massive torque on the ball. After a five pace run-up to the wicket, every ball would be delivered with identical action, but could turn either way or come through as a top-spinner. A subtle signal to the wicketkeeper indicated which type of ball was on its way.

On coming up against a placid wicket, Bradman was known to summarise the pitch condition as, “Even Fleetwood-Smith is not able to turn a ball on that, and if Fleetwood-Smith cannot, no one can.” The man in question could also turn the ball spectacularly on glass topped tables.

O’Reilly observed, “If I only had half of (his cricketing ability), I never would have been worried about bowling against a team which had eleven Bradmans.”

Yet, he played just 10 Test matches.

The eccentric

The squash ball connection should not project Fleetwood-Smith as a man serious about developing his skills. He was as wayward a genius as one could come across, bereft of self-discipline — a trait that would continue to dog him all his life.

It did not help that his career overlapped to a large degree with those of Grimmett and O’Reilly, two of the greatest ever spinners of the world. He also lacked the ability to engage in an intricate battle of wits with the great batsmen, the forte of both Grimmett and O’Reilly. There would be few prolonged battles before he would deceive the batsman through guile, flight and change of pace. His deliveries remained rather fastish and the trajectory more or less the same. The rewards were garnered with the three types of spin that materialised at random and kept many guessing.

Besides, he was eccentric in the truest sense of the word. As O’Reilly recounted, “Chuck, you must remember, was just silly, and totally around the bend.”

During Test matches, he would stand in the field with his back to the action, chatting with spectators. Sometimes he would whistle or break into a song. An ardent supporter of the Port Melbourne Football Club, he would sometimes cheer his team in some imaginary match dreamed up in his head as the cricket action continued in front of him. In crunch situations, he could be seen standing near the boundary, practicing his golf swing — or, even more bizarrely, imitating magpies or kookaburras. Sometimes he would try his hand at catching imaginary butterflies.

He was one of the worst batsmen ever, and his fielding was not much better. And no amount of persuasion could convince him to work on either.

His eccentricities did not stop in the field. He was also prone to misguiding journalists by giving his birth year as 1910 instead of the actual 1908, and also started the rumour that he became a left-arm bowler after breaking his right arm.

Before the hyphen

Leslie O’Brien Smith was born at Stawell in the Northern Grampians area of Western Victoria. His family was involved in the local newspaper business, and his father Fleetwood Smith was a respected member of the community. The nickname ‘Chuck’ caught on fairly early as a boy, supposedly a shortened version of the polo term ‘chukka’.

As a boy Fleetwood-Smith attended the primary school in Stawell. When his family moved to Melbourne in 1917, he enrolled in the Xavier College. It was at Xavier that he played for the first eleven, alongside future Test batsman Leo O’Brien. Also in the team was the future First-Class cricketer Karl Schneider, who tragically died of leukaemia at the age of 23.

It is believed that Fleetwood-Smith was expelled from Xavier shortly after the school won the Victorian Public Schools premiership in 1924. He returned to Stawell with his family and completed his education in a local school. It was here that he started turning out in the Wimmera league for the Stawell cricket club. When he played in a Country Week tournament, plenty of wickets and his unusual bowling action caught the attention of leading cricket clubs of Melbourne. As a result, in 1930, he moved back to Melbourne to play for St Kilda.

By this time, his father had decided to combine his first and last names, with the interjected hyphen. Thus the family became known as the Fleetwood-Smiths and the young cricketer registered as Leslie O’Brien ‘Chuck’ Fleetwood-Smith. It was under this new name that his cricket career was kicked off for St Kilda.

Coming through the grades

At that time, St Kilda had in their ranks spinners of the stature of Bert Ironmonger and Don Blackie– both Test cricketers, the former an all-time great. However, a haul of 16 for 82 against Carlton in 1931-32 propelled Fleetwood-Smith into a regular member of the first team and also underlined his claims to a spot in the Victorian state side.

On debut against Tasmania he captured five wickets in each innings. In the return match against the same state, he once again scalped five in the first innings. And when Victoria came across the touring South Africans in February, Fleetwood-Smith removed six batsmen for 80.

The following month, he made his Sheffield Shield debut and captured 11 wickets against South Australia. This performance saw him being included in Arthur Mailey’s touring side to United States and Canada in the winter of 1932.

It was still tough to break into the Test side with the spin trio of Ironmonger, O’Reilly and Grimmett playing for Australia. And when the Englishmen arrived in 1932-33, Hammond famously thrashed him out of the attack during the tour match against Victoria. His figures read two for 124 in 25 overs. When MCC faced Victoria again, he sent down seven overs and gave away a whopping 67. In between, Victoria also played New South Wales and Bradman treated him with characteristic ruthlessness, hammering his way to 157, leaving the wrist spinner with none for 74 from 14 overs. There were wickets aplenty against the other domestic sides, but against the best batsmen he was yet to prove a potent force.

However, the England manager Plum Warner later wrote that too much attention was given to the performance against a rampaging Hammond and added that he was sanguine about Fleetwood-Smith’s potential as a Test bowler. But the Australian selectors did not agree and there was no Test berth for the Victorian tweaker during the series.

In 1933-34, Fleetwood-Smith captured 41 wickets for Victoria including 12 wickets against South Australia. This saw him travel to England with the team of 1934.

Finally in the Test side

With O’Reilly and Grimmett in the side and Arthur Chipperfield’s leg-spin also used from time to time, there was no opportunity for Fleetwood-Smith in the Tests. However, he captured 106 wickets in the tour matches, at just 19.20 apiece, specifically troubling Maurice Leyland. EvenWisden, which had branded him erratic at first, admitted that he improved remarkably as the tour progressed.

On returning to Australia, Fleetwood-Smith set a Sheffield Shield record by capturing 60 wickets This included 15 in the match against the strong New South Wales boasting seven Test cricketers. The Shield record stood for 62 years until Colin Miller claimed 67 wickets in 1997–98. However, Fleetwood-Smith’s wickets had come in six matches while Miller played as many as 11. Victoria emerged as the winners of the championship.

The following summer, Fleetwood-Smith was chosen to tour South Africa with Vic Richardson’s men. His long awaited debut took place in Durban in the first Test of the 1935-36 series. Given a bowl after Ernie McCormick, McCabe, Grimmett and O’Reilly, he castled Ken Vijloen in his very first over. He ended with four wickets in his first innings.

The rookie bowler proved slightly expensive in the nest two Tests at Johannesburg and Cape Town, but impressed with his curious style and the enormous amounts of turn he extracted. However, playing against Border at East London, he injured his bowling hand and could not play in any more matches on the tour. It required surgery to a tendon of his finger and led to his missing the first two Tests against England in 1936-37.

With Grimmett no longer considered for the Australian team, Fleetwood-Smith came back in the side to play the final three Tests of that riveting series. His 19 wickets were second to only O’Reilly’s 24.

However, during the series he was summoned to appear before the Australian cricket administrators along with McCabe, O’Reilly and O’Brien. The four were charged with “excessive drinking, inattention to fitness and disloyalty to the captain.”

No action was taken and Bradman himself later said that he was not consulted before the meeting. There have been many conjectures that the rap on the knuckles had something to do with the sectarian divide that plagued Australian cricket at the time. Bradman was a Masonic Lodge and so were two of the administrators in the meeting. O’Brien, McCabe and O’Reilly were Catholics and Fleetwood-Smith had attended Xavier – a Roman Catholic School. There was a feeling that a lot of the Catholic players wanted McCabe to be the captain and did not lend their support to Bradman.

However, it is still not very clear why Fleetwood-Smith was made to appear along with the others. Greg Growden, the biographer of our man, says that the left-arm chinaman bowler did enjoy a rare friendship with Bradman, at least during his early days with the Australian team.

Farewell to Tests

The 1938 tour of England saw the bowler’s last appearance for Australia in Test cricket. He did capture 88 First-Class wickets on the tour, at an almost identical average as his earlier visit to the country. But, he did not impress as much. Perhaps the novelty of a left arm wrist spinner had worn off.

The wickets during the series were mostly less than helpful, culminating in that famous Oval run feast. However, Fleetwood Smith with seven scalps and O’Reilly with 10 did play the major role in Australia’s win at Leeds.

At The Oval, however, England piled up 903 with Len Hutton leading the way with 364. Fleetwood-Smith sent down 87 overs to finish with one for 298, the most expensive figures ever in Test cricket. That one bowling performance hauled up his career average from 31.02 to 37.83. With the Second World War breaking out shortly, he never played a Test again.

Fleetwood-Smith’s career ended with 42 wickets in 10 Tests at that unimpressive average. In First-Class cricket, his haul was 597 from 112 games, at 22.64.

Interestingly, Fleetwood-Smith’s strike rate of 44.16 in First-Class cricket was considerably better than Grimmett’s 51.57 and O’Reilly’s 44.16. However, the main differentiator was perhaps the economy rate where his 3.07 runs per over was almost criminally expensive compared to Grimmett’s 2.59 and O’Reilly’s 2.06. His average is at par with Grimmett while it lags behind the incredible 16.60 of O’Reilly. The numbers indicate that he was an excellent strike bowler, but prone to be too inaccurate too often.

A troubled life

During the Second World War, Fleetwood-Smith enlisted in the Second Australian Imperial Force and was posted to the Army’s Physical and Recreational Training School at Frankston. He served as a Warrant Officer alongside Don Bradman. Here too he courted controversy by being involved in a collision with a night-cart while driving a borrowed army vehicle. The army court ordered him to pay the damages. He was discharged in February 1941 on medical grounds.

After the War, Fleetwood-Smith played for Melbourne Club for a season, but other problems were fast catching up with him. His decade long marriage was breaking up. Blessed with good looks and a remarkable resemblance to Clarke Gable, Fleetwood-Smith’s extra marital affairs were legendary. By 1947, the divorce was official and it alienated him from his wife as well as his own family.

Fleetwood-Smith had worked for a few years for the soft-drink business run by his wife’s family. Involved in sales, his job took him to the pubs. As a result his alcohol consumption, never quite moderate, grew beyond critical levels. During the War, he lost his job.

After his divorce, Fleetwood-Smith married the sister of one of his teammates of the Melbourne Club and worked at a variety of menial jobs. But with time, he became a chronic alcoholic and his second marriage went the same way as the first.

He spent several of his last years as a homeless vagrant on the streets of Melbourne. He was known to sleep a few hundred metres from the stadium which had seen him perform several of his renowned feats.

In March 1969, Fleetwood-Smith was arrested for vagrancy. With another man in tow, he was also charged with having stolen $85 from a woman’s purse. The 60-year-old former Australian cricketer gave his address as the Gill Memorial Hostel, a home in the city run by the Salvation Army. Police informers testified that he was a well-known vagrant in the area.

Flashed in the papers, the news of his arrest shocked the Australian cricket circles. Many influential friends – which included the cricket loving former Prime Minister Sir Robert Menzies – arranged for legal assistance. Although his accomplice was charged and convicted, the hearing for the Test cricketer was adjourned. He walked out of the City Court on a $20 good-behaviour bond.

His friends had arranged for new quarters and his estranged second wife came back to stay with him and help him start a new life.

But, by then it was much too late. Health problems were at far too advanced a stage and Fleetwood-Smith died of cancer in March 1971.