Sam Loxton, born on March 29, 1921, was a belligerent batsman and a big-hearted bowler who served as an important member of Don Bradman’s Invincibles of 1948. Arunabha Sengupta looks back at the life and career of the man who once snapped back at the Prime Minister for criticising his way of getting out.

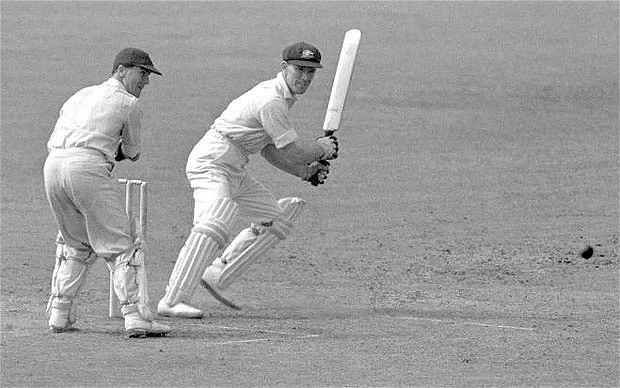

Loxton at Leeds

It is not often that we remember The Invincibles of 1948 with their backs to the wall. The team led by Don Bradman on his farewell tour vanquished almost everything in sight. But, at one stage during the Headingley Test, they were indeed up against it, with England well over 400 for the loss of just two wickets.

The match is remembered for the epic chase on the final day on a turning wicket, when Bradman and Arthur Morris mastered the English bowlers to enable Australia get the 400 plus runs for the loss of just three wickets. However, it had been a rough ride for the visitors for much of the match — and such extenuating circumstances generally brought out the best in Sam Loxton.

During the England innings, the two-Test old Loxton, former Victorian Footballer, was standing in the covers. He had spent most of the day looking at the face of the blades of Len Hutton, Cyril Washbrook and Bill Edrich, and had just finished sending down a long fruitless spell. And now, an Edrich drive sped past him into the vast outfield and the all-rounder turned to give chase.

He ran across the historic turf like a greyhound, without any sign of fatigue. When the ball beat him to the fence, he could not stop himself and cannoned into the crowd, scattering the spectators around him. Having finally managed to control his momentum, he hurled his cap down in mock-disgust at having failed to stop the boundary. It earned him many a laugh.

Ray Lindwall, Keith Miller, Bill Johnston and Ernie Toshack constituted a formidable attack, but their figures in the first innings were rather ordinary. Yet, Loxton ran in with his large heart, his spirit indomitable, and polished off the tail to finish with excellent figures of 26-4-55-3. England, 423 for two at one stage, were all out for 496.

Yet, the hosts for once remained in the driver’s seat. Alec Bedser and Dick Pollard dismissed the openers with just a few runs on the board. And then Pollard sent down the ball that castled The Don for just 33. When captain Norman Yardley got rid of Miller, Australia were in a lot of trouble at 189 for four. Loxton strode in to join his great friend — the 19-year-old Neil Harvey. The youthful left-hander greeted him with the words, “Slox, they can’t bowl.”

Thus reassured, Loxton tucked into the fare. Five sixes were slammed in the innings, four off Jim Laker and the other a straight drive off Lancashire medium pacer Ken Cranston. Neville Carduswrote that he got a crick in the neck from watching the ball steepling so high into the stratosphere. And Bradman considered the six off Cranston as the finest he had ever seen. The Australian captain later recalled Loxton’s innings as “the very essence of belligerence”. He added the rather curious simile, “When Loxton hits the ball it is the music of a sledgehammer, not a dinner gong.”

When Harvey reached his century, Loxton was visibly delighted, leaving his crease in a hurry to shake his mate’s hand, almost getting run out in the process. And with his own score on 93, he went for a mighty slog off Yardley and was bowled.

He walked into the dressing room and there, along with the Australian players, sat Robert Menzies— the Australian Prime Minister and an unabashed lover of the game. “That was a pretty stupid thing to do. You could have made a century,” the statesman chided. And Loxton shot back, “Haven’t you made a few mistakes in your time too?”

At the end of the tour, Bradman wrote: “Loxton did a magnificent job as utility player. Extremely powerful driver and the best player of the lofted drive among the moderns. Tremendous fighter, always throwing every ounce into the game. Fast-medium bowler who could keep going for long spells — on occasions bowled really fast and worried the best batsmen.”

For good measure, the legend added: “The most dangerous field in the team. Did stupendous things to get run-outs. I have never seen anyone who had such a powerful throw when off balance.”

Loxton’s brilliance in the field was demonstrated during the Manchester Test, when Denis Compton and Bedser had been in the midst of a stubborn partnership. Bradman and he both chased a stroke through the covers, and both overran the ball without picking it up. This prompted the batsmen to try to steal an additional run, and Loxton swooped up the ball and sent in a sharp return to catch Bedser short of his ground.

If he had not caught the leading edge of his own sweep off Freddie Brown on his nose, Loxton might have been one of the several Australians to complete 1000 runs on the tour. He ended with 973, missing the last two matches because of the injury.

The South African safari

Although Menzies rued his missed century, Loxton did not have to wait too long to get his maiden Test hundred. On Australia’s next tour — to South Africa in 1949-50 — he hit 101 in the first Test at Johannesburg, another exhilarating innings played in just two hours and a quarter.

However, it was not that he was always a happy hitter. In the subsequent Tests, Loxton had a few memorable partnerships with Harvey in which he displayed immense character and resolve.

In the second Test at Cape Town, Harvey scored 178, adding a crucial 140 with Loxton for the fifth wicket. The all-rounder contributed just 35.

And then there was the immortal third Test at Durban. In the first innings Loxton batted at No. 10, and Harvey at No 9, as skipper Lindsay Hassett reversed the batting order on a sticky surface. Australia were all out for 75 in reply to 311. When South Africa themselves were bowled out for 99 in the second innings, the visitors needed 336 for a win — a tough ask given the scores in the last couple of innings. Loxton came in with the score reading 95 for four and the first delivery from Hugh Tayfield passed precariously close to the edge of his bat. He was also caught at long-on off a no-ball. But, the Victorian all-rounder put all that behind him. As Harvey essayed an innings of light-footed genius, Loxton put his head down to grind out an obstinate 54 in 166 minutes. The partnership was worth 135 and turned the match completely. Australia won by five wickets.

Loxton just played five more Tests after that and did not really do too much with either bat or ball. And he lost his place in the side after some ordinary performances when Brown’s men were in Australia the following Antipodean summer. However, he never lacked intent at the crease, sincerity when running in with the ball or effort in the field. He was always a player of limited ability, but made up for it with spirit that extended far beyond potential.

Football, Cricket and War

Loxton was born on March 28, 1921, at Albert Park, Victoria. Father Sam Sr was an electrician and an enthusiastic cricketer, playing second grade cricket for Collingwood.

As a boy Loxton went to the Yarra Park State School, batting in front of a pine tree in the schoolyard. This particular tree had been historically used as the stumps by several Test cricketers including Vernon Ransford and Ernie McCormick.

When the Loxtons moved to Armadale, the lad joined the city’s Public School before moving to Wesley College, Melbourne. One of his schoolmates at Wesley was Ian Johnson, later his Australian teammate and a future captain of the national team. Loxton and Johnson were coached at Wesley by P. L. Williams, who had earlier guided Ross Gregory and Lindsay Hassett.

The Loxton family was also heavily involved with the Prahran Club. Father Sam was the scorer, drove the mattig and equipment to the games, served as a member of the club committee and later became the vice-president. Mother Annie supplied the cucumber sandwiches for nearly a quarter century. Loxton played district cricket for the club’s third grade team when he was just 12.

After the Colts were disbanded in 1940-41, Loxton moved back to Prahran and played for the first grade team of the club.

By 1942, Loxton had become a star in his other favourite sport. He made his debut in the Victorian Football League, playing for St Kilda. In his very first match Loxton kicked five goals, finishing with 15 for the season in his six matches.

If in cricket Loxton was an all-rounder, so was he in Australian rules football. He turned out both as a forward and a defender. And it was on the football field that he came across another great all-rounder. Keith Miller was a teammate at St Kilda and the two often combined in surging attacks.

Enlisting for World War II at Oakleigh in July 1942, Loxton served with the 2nd Armoured Division. At the time of his discharge in November 1945, he held the rank of a sergeant.

L

It is not often that we remember The Invincibles of 1948 with their backs to the wall. The team led by Don Bradman on his farewell tour vanquished almost everything in sight. But, at one stage during the Headingley Test, they were indeed up against it, with England well over 400 for the loss of just two wickets.

The match is remembered for the epic chase on the final day on a turning wicket, when Bradman and Arthur Morris mastered the English bowlers to enable Australia get the 400 plus runs for the loss of just three wickets. However, it had been a rough ride for the visitors for much of the match — and such extenuating circumstances generally brought out the best in Sam Loxton.

During the England innings, the two-Test old Loxton, former Victorian Footballer, was standing in the covers. He had spent most of the day looking at the face of the blades of Len Hutton, Cyril Washbrook and Bill Edrich, and had just finished sending down a long fruitless spell. And now, an Edrich drive sped past him into the vast outfield and the all-rounder turned to give chase.

He ran across the historic turf like a greyhound, without any sign of fatigue. When the ball beat him to the fence, he could not stop himself and cannoned into the crowd, scattering the spectators around him. Having finally managed to control his momentum, he hurled his cap down in mock-disgust at having failed to stop the boundary. It earned him many a laugh.

Ray Lindwall, Keith Miller, Bill Johnston and Ernie Toshack constituted a formidable attack, but their figures in the first innings were rather ordinary. Yet, Loxton ran in with his large heart, his spirit indomitable, and polished off the tail to finish with excellent figures of 26-4-55-3. England, 423 for two at one stage, were all out for 496.

Yet, the hosts for once remained in the driver’s seat. Alec Bedser and Dick Pollard dismissed the openers with just a few runs on the board. And then Pollard sent down the ball that castled The Don for just 33. When captain Norman Yardley got rid of Miller, Australia were in a lot of trouble at 189 for four. Loxton strode in to join his great friend — the 19-year-old Neil Harvey. The youthful left-hander greeted him with the words, “Slox, they can’t bowl.”

Thus reassured, Loxton tucked into the fare. Five sixes were slammed in the innings, four off Jim Laker and the other a straight drive off Lancashire medium pacer Ken Cranston. Neville Carduswrote that he got a crick in the neck from watching the ball steepling so high into the stratosphere. And Bradman considered the six off Cranston as the finest he had ever seen. The Australian captain later recalled Loxton’s innings as “the very essence of belligerence”. He added the rather curious simile, “When Loxton hits the ball it is the music of a sledgehammer, not a dinner gong.”

When Harvey reached his century, Loxton was visibly delighted, leaving his crease in a hurry to shake his mate’s hand, almost getting run out in the process. And with his own score on 93, he went for a mighty slog off Yardley and was bowled.

He walked into the dressing room and there, along with the Australian players, sat Robert Menzies— the Australian Prime Minister and an unabashed lover of the game. “That was a pretty stupid thing to do. You could have made a century,” the statesman chided. And Loxton shot back, “Haven’t you made a few mistakes in your time too?”

At the end of the tour, Bradman wrote: “Loxton did a magnificent job as utility player. Extremely powerful driver and the best player of the lofted drive among the moderns. Tremendous fighter, always throwing every ounce into the game. Fast-medium bowler who could keep going for long spells — on occasions bowled really fast and worried the best batsmen.”

For good measure, the legend added: “The most dangerous field in the team. Did stupendous things to get run-outs. I have never seen anyone who had such a powerful throw when off balance.”

Loxton’s brilliance in the field was demonstrated during the Manchester Test, when Denis Compton and Bedser had been in the midst of a stubborn partnership. Bradman and he both chased a stroke through the covers, and both overran the ball without picking it up. This prompted the batsmen to try to steal an additional run, and Loxton swooped up the ball and sent in a sharp return to catch Bedser short of his ground.

If he had not caught the leading edge of his own sweep off Freddie Brown on his nose, Loxton might have been one of the several Australians to complete 1000 runs on the tour. He ended with 973, missing the last two matches because of the injury.

oxton played his final season for St Kilda in 1946 before retiring from top-tier football to concentrate on cricket. His total number of goals was an impressive 114. Had the War not intervened, he perhaps could have enjoyed rather more success in Australian Rules Football.

When First-Class cricket resumed in 1945-46, the Victorian did not manage to find a place in the state side. However, after retiring from football he started putting in more time in the game, and broke into the Victoria side in December 1946.

Five of the regular players were away because of the ongoing Test series against Wally Hammond’s men, and Loxton was one of the new faces selected to make up the numbers. Indeed, he did much more than that, scoring an unbeaten 232, adding 289 runs with Doug Ring for the sixth wicket. It remained his highest score in First-Class cricket.

The indomitable spirit was on display even in this first match. At 183, Loxton went for a hook and somehow succeeded in hitting himself on the head with his willow. However, he continued to bat, remained unconquered, and then opened the bowling and took a wicket before being rushed to the hospital with a concussion. He returned to pick up two more wickets in the second innings. This performance secured a place for him even after the return of the Test players. Loxton continued to score heavily and pick up useful wickets to end the season at the top of both batting and bowling averages for his state.

Test debut

He was not so successful in the following season, but did enough to impress Bradman. With the series against Lala Amarnath’s Indians already convincingly wrapped up, a few key players were rested and Loxton, along with Doug Ring and Len Johnson, were blooded in the fifth and final Test at Melboune.

Playing in front of his home crowd, Loxton batted at No 6, scored 80 and added 159 with Harvey in the first innings. He followed it up with two top order wickets when the Indians batted. The newcomer had done enough to be chosen for the famous tour of 1948. As he later reflected: “It’s not the fellow who gets the opportunity it’s the fellow who puts his hands around it and grabs it. I just happened to be in the right place at the right time.”

Post-Test career

After being dropped from the national team following the 1950-51 Ashes, Loxton continued to play for his state for seven more years, on occasions shining with the bat or the ball. In 1951-52, his furious hit through the covers was stopped by Jackie McGlew, the vice-captain of the visiting Springbok side. It broke the fieldsman’s little finger in three different places. Loxton was characteristically blunt in his reaction: “You had no business getting in the way.”

In 1953–54, Loxton toured India as part of a Commonwealth team. He did not really blaze the turf but put in some memorable performances, mainly a 123 and five for 92 against a strong Bombay side.

He retired after the 1957–58 season, having enjoyed a reasonably successful summer. Loxton finished with 6249 runs at 36.97 and 232 wickets at 25.73 from his 140 First-Class matches. In 12 Tests, he managed 554 runs at 36.93 and captured eight wickets at 43.62. He continued to turn out for Prahran for another four seasons.

Before the end of his playing days, Loxton was called up as a commentator on GTV-9 for the Melbourne Summer Olympics held in 1956. One of his co-commentators was the legendary American athlete, Jesse Owens.

The style

On the field, Loxton was known for his enthusiasm and aggression. His batting, as discussed earlier, was generally marked by blisteringly attack, although he could also temper his approach according to the situation. He enjoyed facing fast bowling, especially short pitched stuff rearing for his head. His initial back and across movement — first back and then across in two separate steps — helped him in this aspect. He hooked fearlessly, drove hard, was one of the best exponents of the lofted drive, and was also a furious cutter of the ball.

As a bowler, he was at best fast medium and had the ability to swing the ball both ways. Quite often he resorted to intimidating and short-pitched bowling even though he was hardly the fastest. He famously bowled an eight-ball over to the young Norman O’Neill, each and every ball aimed at the upper body, and most of them clinically dispatched to square leg fence repeatedly. Outspoken spinner Bill O’Reilly, while agreeing about his commitment and zeal, always maintained that Loxton’s bowling was too limited to make a mark on the international game. John Arlott was succinct in his description that his bowling was “of no great subtlety, but he (was) always endeavouring to bowl the fastest ball ever bowled.”

On the field he was a livewire, always eager, always alert, with a penchant for sending in hard and fast throws, and hitting the wicket from impossible angles. Don Tallon once complained about the scorchingly sharp returns sent in even when there was no chance of a run out, throws that tended to damage the wicketkeeper’s fingers.

His great friend Harvey recalled, “No one put more into cricket than Sam did, both on the field and off it, and no one took less out of it.”

It was again left to Arlott to beautifully capture Loxton’s approach to the game with the words: “Eleven Loxtons would defeat the world – at anything.”

The ‘diplomat’

Loxton served as the manager of the Australian team on the tour to Pakistan and India in 1959-60. Thus he became the first manager since the World War II who was not a member of the Australian Board of Control. Loxton himself hinted that the difficulties associated with a tour of the subcontinent was responsible for this appointment: “What board member would be silly enough to go there?”

By then, his playing days had come to an end, underlining his blunt nature as much as his on-field deeds. The appointment as manager was looked at with some reservation and not a little comic element. As Gideon Haigh noted in The Summer Game, “Thoughts of such a gruff, soldierly man acting the diplomat had caused great ribaldry.” Loxton’s former captain Hassett also rubbed it in by remarking at a dinner: “I would advise the Prime Minister Mr. Menzies to have army and navy standing by. A week after Sam gets to India, war is bound to break out.”

The tour saw several critical administrative issues surrounding payments and wickets. Loxton came through all that in flying colours, his blunt approach and rather quick witted responses helping the Australian cause immensely.

At Kanpur, he steadfastly refused to start a match because the Australian cricketers had not received their scheduled payment from the Indian administrators. The tactic worked and the cheque materialised soon enough.

At Lahore, he was approached by an irate General Ayub Khan, head of the ruling military junta, who demanded to know why Pakistan had not been invited to Australia for a reciprocal tour. The actual reason was the lack of public interest in a series against Pakistan, but Loxton seized the opportunity to complain about the matting wickets. When the Test match at Karachi also greeted them with a matting track, Ayub Khan threatened to shoot the groundsmen if they prepared any surface other than turf.

The First Test against Pakistan at Dacca also had an interesting sidelight centred around Loxton. One of the umpires took off his shoes and put them on the ground while play was in progress. The Australian manager clicked a picture of the scene and sent the snap across to the MCC. Along with the photo was a query : Would a batsman be out if the ball struck the umpire’s loose shoes and bounced up into a fielder’s hands. He did not receive a reply.

The selector

After retirement, Loxton served as a selector of Victoria from 1957 to 1980–81. He was also an MCG trustee for 20 years from 1962 to 1982.

In 1970, he became a selector of the Australian cricket team joining Bradman and Harvey in the panel, and served in the capacity for 11 years. One of the players he recommended in 1970-71 was Dennis Lillee. The other major Loxton selection was David Hookes in 1977 on the eve of the Centenary Test.

However, with the turmoil surrounding pay scale and the Packer circus, Loxton’s later years as a selector proved to be rather rocky. With the major cricketers unavailable for the Test matches, Loxton and his co-selectors recalled 42-year-old Bobby Simpson to become the captain in 1977.

In February 1981, Loxton was at the MCG as Australia played the infamous One Day International (ODI) against New Zealand. When captain Greg Chappell instructed brother Trevor to bowl the last delivery underarm, the veteran Victorian supposedly broke down and wept. Later he told the skipper, “You may have won the match, but you lost a lot of friends.”

Disillusioned with increasing problems with player behaviour and the amount of money coming into the game, in April 1981 Loxton announced that he was severing all connections with cricket.

In 1955, Loxton had given up his job as a bank teller and had entered the political scene. He had narrowly won the seat of Prahran in the Victorian Legislative Assembly for the Liberal Country Party. He held the seat till 1979, winning by more comfortable margins in each subsequent election. He served as a government whip from 1961 until 1979, and was awarded an OBE for his services both as a cricketer and politician.

The last days

After 1981, Loxton moved to the Queensland’s Gold Coast and he remained in contact with cricket by umpiring in the local matches. Down the years, his eyesight deteriorated and he could no longer officiate in games. However, he kept going to cricket grounds to attend matches even when he could no longer see the pitch from the boundary.

In December 2000, Loxton suffered a bizarre double tragedy. His third wife, Jo, drowned in the family swimming-pool. On the very same day Michael, one of his sons from his second marriage, was killed by a shark attack in Fiji.

Loxton spent final days alone, almost blind but still active and blunt. In 2008, he told Cricinfo,“Shane Warne’s been a fine bowler—no doubt about it, he’s done some wonderful things — but Bill O’Reilly and Clarrie Grimmett, who have better strike-rates per match than Shane Warne and never played against a 2nd XI [the likes of Bangladesh and Zimbabwe] — they only played against the best— had no rough to bowl at. I never had to bat to a leg-spinner who bowled into the rough outside my leg stump, and I played for a long time.”

The memories of good old days do produce such symptoms of rosy retrospection. Grimmett’s average of 24 per wicket actually shot up to 32 against England, much of his figures immensely helped by the matches against the weaker sides of South Africa and West Indies. O’Reilly’s eight wickets at 4.12 in his only Test against New Zealand and 34 more against West Indies at 18.64 did not really harm his cause. Shane Warne’s 27.27 against Bangladesh was actually higher than his career average of 25.41. But, then, such a tinge of bias accompanying happy thoughts about the days of yore is common and can be viewed with indulgence.

Loxton passed away on December 3, 2011, passing on the mantle of the oldest living Australian Test cricketer to Arthur Morris.