November 27, 1978. The first Day Night One-Day International (ODI) was played at Sydney Cricket Ground. The contestants were West Indies and Australia. Almost exactly a year earlier, the ground had hosted the first Day Night match, during Kerry Packer’s World Series Cricket. The teams had been the same, with WSC tags preceding their names. Arunabha Sengupta looks at the landmark matches, also tracing the history of the first ever cricket match played under lights — between Middlesex and Arsenal.

The sun never sets on cricket

It started at 2 PM, on a balmy sun-soaked afternoon at the Sydney Cricket Ground, on November 28, 1978. And it was taken to its logical conclusion almost exactly a year later at the same ground on November 27, 1979.

Well, we do have to add that cricket in the dark had been kicked off rather hesitantly as early as on a summer evening of 1952, but that had not really captured the imagination of the public. Kerry Packer’s experiment did. The concept of pyjama cricket, white balls and coloured clothing was born. And it was there to stay. Cricket never looked back.

The kick-off

From the earliest days, cricket had been played under the sun — through its infancy into adulthood, from paddocks to villages to shires and then in stadiums across the Empire. And it did not look likely to change.

Indeed, alteration was wrought not by the cricket administrators, but the innovative thought of the most astute entrepreneur the game has witnessed. And before that, it had been experimented with as a by-product of the efforts legendary football manager.

It had been Herbert Chapman, the great manager of Arsenal, who had projected the futuristic vision of matches under floodlights. That had been in the early 1930s. Two decades later, in the summer of 1951, lights had been installed at the Highbury Stadium in North London. In October of that year, Arsenal had played Rangers under the lights and it had attracted over 60,000 spectators.

It had been an exhibition game. The first league match under lights would not take place for another five years.

The following August the Compton connection was at play. Denis Compton had been a part of the FA Cup winning Arsenal side in 1950, and switched to don the Middlesex whites in the summer. His brother Leslie Compton represented Arsenal. Hence the football club was quite used to hosting friendly cricket encounters.

The Compton brothers enjoyed a benefit cricket match apiece, both played between Middlesex and Arsenal at Highbury. Denis Compton’s benefit was played in 1949, and Leslie’s in 1955. Both these matches were normal day games.

However, on August 11, 1952, the world witnessed the first cricket match under lights. This one was the benefit game of the Middlesex and England left-arm spinner Jack Young.

Middlesex, playing Surrey in a Championship game at The Oval, arrived weary and just about in time for the 7:30 PM start. The Arsenal side emerged as usual from their tunnel, kicking footballs with zest. The Bedser twins — Alec and Eric — performed the role of the umpires.

The 13-a-side game was played on a black matting wicket laid on the centre circle. The balls and stumps were white, but only due to elaborately applied paint. The match had to be held up time and again as the balls lost paint after being knocked around.

The game was watched by 7000 spectators and telecast live on BBC. Arsenal scored 189. Middlesex, in response, got there with some strife and, in the end, with style. Bill Edrich scored 70. Young, the beneficiary, walked in at 187 for nine wearing a miner’s lamp, and knocked off the winning runs.

Since television time had been booked, the game was carried on till 10:30 PM even after the match had been decided. Middlesex ended at 237 for 11. The following day the county team was back to play their more serious game against the strong Surrey side. They lost.

Even though it had provided lots of entertainment, the Timeswas far from convinced. Their pessimistic assessment read: “What is to prevent non-stop Test matches where the last wicket falls as the milkman arrives? At least there will be no appealing against the light.”

The lights were switched off and the sun took over yet again.

And then came Packer

The World Series Cricket revolution changed cricket forever.

After teaming up with Jack Nicklaus to make a smash hit of the Australian Open Golf on television, Packer turned his attention to cricket. And when the Australian Cricket Board refused the rights of Sheffield Shield and Test cricket, the media mogul launched his own parallel cricket circuit.

The best cricketers were recruited, from Australia, West Indies, South Africa, Pakistan, as well as a few from England. When the official boards resisted, games were played in makeshift cricket grounds with drop in pitches. The World Series saw some furious, fascinating contests. Yet, the response was lukewarm to start with.

Only a couple of thousand watched the first Super Test between Australia and West Indies at the VLF Park. Eying the low turnout, Packer racked his brain furiously. Millions of dollars were spent in putting up huge lighting towers.

On December 14, 1977, a miscellaneous one day match of the World Series Cricket extravaganza was organised. It was held at the same VLF park and was watched by some 6000 spectators. The game was between WSC World XI and WSC Australians. It was played under lights. Greg Chappell snapped up three wickets and scored a 48-ball 59. The Australians won with lots to spare. And night cricket experiments had resumed.

The charge of the light brigade

And finally on November 28, on a sunny Tuesday afternoon, thousands of people queued at the Sydney Cricket Ground gates.

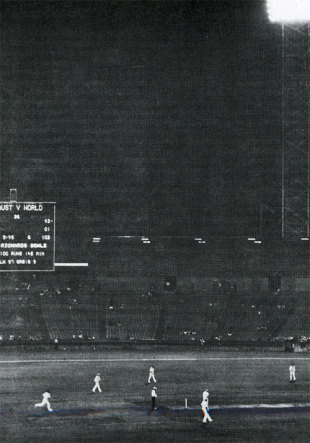

Six enormous floodlights towers had been set up round the stadium. The million dollar gamble of Melbourne had been repeated. And this time it was an ‘official’ match of the World Series Cricket International Cup, between the WSC Australia and the WSC West Indies.

In the end, there was such a rush that gates were thrown open to avoid crowd stampede. People swarmed in like waves. Majority were young, beer bottles filled to the brim, eager to party through the night. The older folk came along as well, to see what the fuss was all about.

The crowd was delighted with the atmosphere, soaking under the sun and basking under the lights. They cheered every run, every wicket, every catch. And they sang. There was a new song written specifically for the night game.

While the first Super Test at VLF Park had seen just 2,000 people, the first Day Night match at a major venue was witnessed by 44,377 according to the official figure. But estimates say it was more than 50,000.

The cricket was riveting as well. The ball moved. Dennis Lillee trapped Richard Austin plumb for six, and then bowled Viv Richards for a second-ball duck. Greg Chappell ran in with his medium pacers and skittled out five men. Only Gordon Greenidge resisted with 41. The West Indian innings was over before the lights were switched on. It had amounted to 128.

Andy Roberts and Joel Garner made sure that the lights did shine. They made the home side sweat for every run. In the end, victory was achieved by five wickets in the 37th over. The merry crowd, full of food, drink, song and spirit, walked out after witnessing history. The lights were switched off.

It had been a tipping point in the evolution of cricket. A shift of cricket’s centre of gravity. Cricket would never be the same again.

The official beam

A year later, almost to the day, on November 27, 1979, West Indies and Australia met once again under lights, at the same Sydney Cricket Ground. Eleven of the 22 players had taken part in the match a year earlier — four Australians and seven West Indians.

This time, however, there was official stamp on the encounter. During the course of the year, Packer had got his television rights, the Boards had got back their players, the cricketers had signed contracts with better remuneration.

Hence, on this day was played the first official ODI under lights. And the result was the same.

Lillee snapped up Greenidge and Richards cheaply in his six splendid overs. Len Pascoe unsettled the Windies men with his pace. The visitors could manage just 193.

Once again Roberts, Michael Holding, Garner and Colin Croft tried their level best to defend the total. But a classy unbeaten 74 by Greg Chappell, and an audacious 52 by Kim Hughes, settled the issue. Once again Australia triumphed by five wickets.

Day Night cricket was here to stay.

Brief scores

Match 1 — August 12, 1952

Arsenal 189 (C Grimshaw 65, D Bennett 36, C Holton 30; Bill Edrich 4 for 19, Alexander Thomson 5 for 9) lost to Middlesex 237 for 11 (Jack Robertson 31, Bill Edrich 70, Sydney Brown 39) by 3 wickets. Match officially over at 190 for 9. 13-a-side match.

Match 2 — November 28, 1978

WSC West Indies 128 (Gordon Greenidge 41; Dennis Lillee 4 for 13, Greg Chappell 5 for 19) lost toWSC Australia 129 for 5 (Ian Davis 48*) by 5 wickets

Match 3 — November 27, 19790

West Indies 193 (Alvin Kallicharran 49; Len Pascoe 4 for 29, Allan Border 3 for 36) lost toAustralia 196 for 5 (Greg Chappell 74*, Kim Hughes 52) by 5 wickets