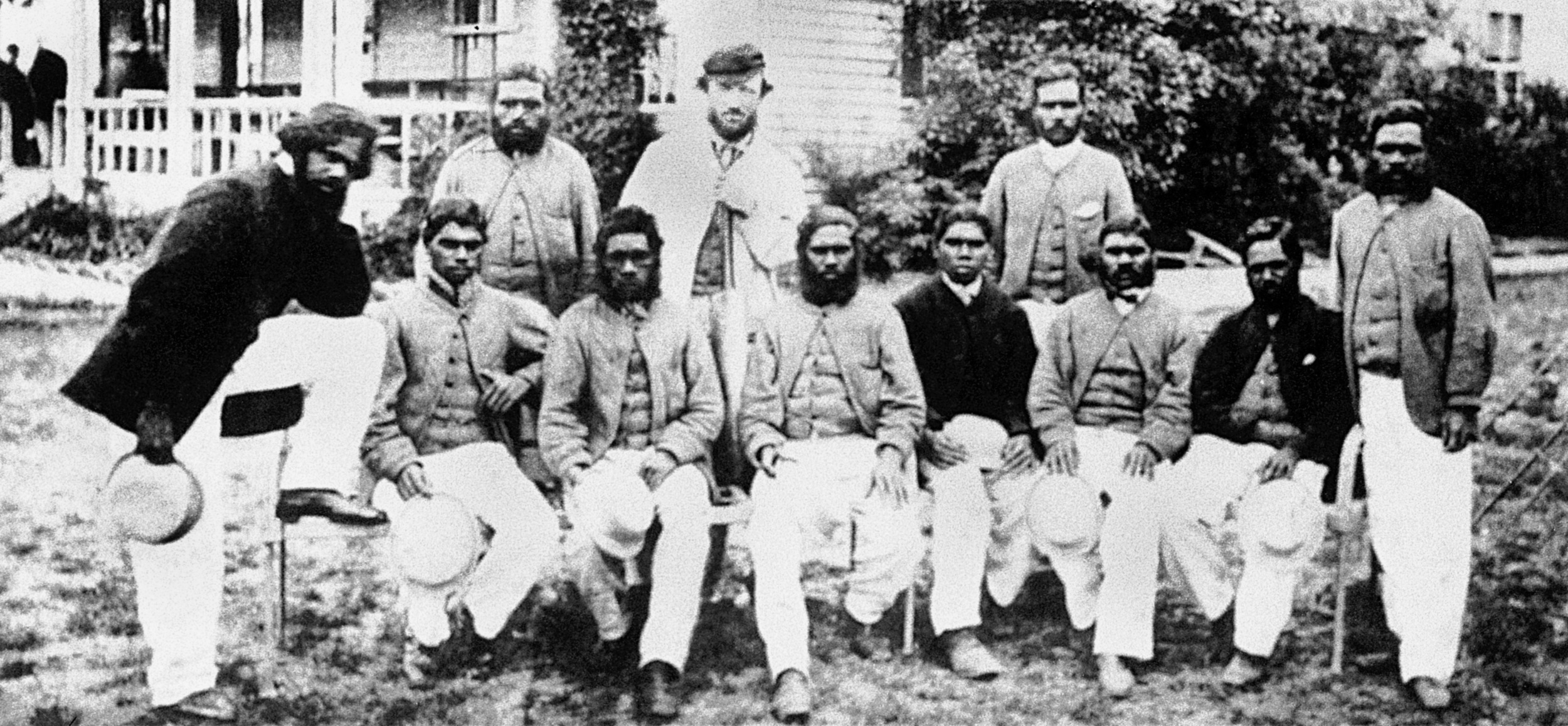

The first team of English cricketers to tour Australia (1861-62)

Standing (left to right): George Bennett, William Mudie, William Caffyn, HH Stephenson (Captain), George Griffith, Mr. WB Mallam (in the top hat), Roger Iddison, Thomas Hearne, Edwin Ned Stephenson.

Seated in front: Charles Lawrence, William Mortlock, and Tom Sewell

The epochal first ever Australian cricket tour to England remains one of the most curious tale of sporting relations. In this series, Pradip Dhole traces the journey and deeds of the Aboriginal cricketers, which remain surprising even after a century and half, and also relates the story behind the men who made this incredible venture possible.

Part 1

Dickensian

The next cricket connection in the life of Charles Lawrence was to spring somewhat unexpectedly from the Antipodean city of Melbourne on the initiative of the proprietors of the catering firm of the hoteliers, Felix Spiers and Christopher Pond, based in the Victorian city. Perhaps it would be appropriate that this point to stress the significance of Melbourne with respect to the events that were to follow. Thanks to the Australian Gold Rush of the 1850s, Victoria had become the largest, the most prosperous, and the most populated of the Australian colonies by this time. Indeed, it is estimated that between 1851 and 1861, Victoria had produced about 88% of Australia’s total gold, and the local economy was experiencing an unprecedented boom, and prosperity was in the air.

Revelling in their new-found wealth within a prosperous community, Spiers and Pond decided to dispatch one Mr. William Mallam to England as their emissary with a lucrative offer for the celebrated English novelist, Charles Dickens in early 1861. The story of their joint efforts to lure the great English novelist to Australia for a 12-month long lecture and reading tour of his novels for a handsome consideration is too well known to bear repetition here.

It is said that the great novelist had been rather non-committal about the overture at first and had then decided to delay his response to the offer, finally declining the generosity of the duo altogether on health grounds. There may have also been an element of family disquiet in the refusal by Dickens to undertake the long assignment in Australia. In 1858, Charles Dickens had seemingly abandoned his legally married wife for the charms of a young actress called Phyllis Rose, and the ensuing public scandal, fanned by a vitriolic Press, may have been weighing very heavily on his mind at the time.

While the story of the negative response from Dickens is generally well known, there appears to have been one other personage who had been instrumental in the sequence of events to follow. George Selth Coppin was an expatriate Englishman born in Sussex, and he had emigrated to Australia in 1842, becoming a well-known comic actor, violinist, and a multi-faceted entrepreneur of high repute in Melbourne in the immediate post Gold Rush period of Australia. His proximity to Speirs and Pond arose from his famous Melbourne landmark, Coppin’s Theatre Royal, situated almost opposite to the Café de Paris and the Royal Hotel, two of the popular eateries belonging to the renowned hoteliers in Bourke Street, Melbourne.

Keeping in mind the popularity and success of the cricket tour that had been arranged by George Parr of Nottinghamshire, often referred to as being the “Lion of the North” to North America in the 1859 season, and sensing a profitable business opportunity, Coppin advised Spiers and Pond to explore the possibility of a cricket tour by an English team to Australia. The financial aspect of the suggestion appealed to the affluent hoteliers, who then instructed their agent, Mr Mallam, already in England, to negotiate a cricket tour of Australia by English cricketers. Accordingly, the faithful Mr Mallam is known to have travelled to Birmingham in Sep/1861 to witness the North v South match, the last first-class match of the season, played at Aston Park, also known as Villa Park, from 5 Sep/1861. The rival skippers of the respective teams were John Lillywhite (South) and George Parr (North). South won the game by 43 runs.

At some time after the game, Mr. Mallam met the players of both teams at the nearby Hen and Chicken Hotel of the prosperous city of Birmingham and explained the proposal from his principals to them. He related to them the plan for a cricket tour of Australia by an English team for the 1861/62 English winter. It was to be a business scheme by which each member of the touring team was to receive £ 150, first class passage, plus a total of about £7000 for the duration of the tour as expenses. Twelve members of the assembled company accepted the offer on the stated terms, including Heathfield Stephenson (Surrey), and agreed in principle to undertake the pioneering cricket tour.

The proposed touring party of 12 professional cricketers was eventually constituted as follows: Heathfield Stephenson a right hand batsman, right-arm round arm fast bowler and occasional wicketkeeper, William “Billy” Caffyn, William “Will” Mortlock, George “Ben” or, more popularly, “Lion Hitter” Griffith, William Mudie, Thomas Sewell Jnr. (all from Surrey), Roger Iddison, wicketkeeper Edwin “Ned” Stephenson (both from Yorkshire), Thomas Hearne, Charles Lawrence (both from Middlesex), George Wells (Sussex), and George “Farmer” Bennett (Kent). While it may not have been the most balanced English squad that could have been assembled at the time, it was very definitely the first to tour Australia.

The upshot of the Birmingham meeting culminated in the chosen group gathering at the photographic studio of M/S McLean, Melhuish & Company at 26, Haymarket Street, London, for a team photograph, an iconic image, being the first photographic record of any team of English cricketers embarking on a tour of Australia. The historic image is reproduced at the beginning of this part.

Down Under

Almost all events pertaining to this initial venture by the All England team to Australia, however seemingly commonplace, have gradually become associated with the legend of the great rivalry between the two great cricketing nations. Thus, when Voyage # 21 of the dream vessel of the great British engineer and entrepreneur of the 1800s, Isambard Kingdom Brunel, the SS Great Britain, set sail from Liverpool on Oct 10, 1861, carrying the English cricket team among the other passengers, arriving at Melbourne on Christmas Eve of 1861, the 67-day voyage was destined to set off the gradual unfolding of the saga surrounding the greatest cricketing rivalry of the world.

It seems that, following the usual custom at the time, and in a bid to relieve the tedium of the long voyages, passenger vessels used to have their own in-house newspapers in those days. The news journal of the SS Great Britain was known as The Cabinet and was published on a weekly basis, one Alexander Reid shouldering the editorial duties of the paper. The issue dated Nov 9, 1861 carried a short article entitled “Our Distinguished Passengers”, complete with brief pen-pictures of the individual players. It is believed that Mr. William Mallam had contributed valuable information about the individual members of the touring English cricket team for the benefit of the editor of the paper.

In his dissertation entitled Heritage, Nationalism, Identity: The 1861-62 England Cricket Tour of Australia, written by Warwick Frost, and appearing in The International Journal of the History of Sport, the author postulates that the historical significance of the tour should be evaluated against the backdrop of the Australian Gold Rush of the 1850s, bringing with it its attendant prosperity for the immigrant white population of Australia and the general economic prosperity sparked off by the discovery of gold in some Australian colonies, namely New South Wales and Victoria. He also discourses on the gradual and steady evolution of the independent Australian national (as distinct from the Colonial British) identity.

“Against this background, an examination of the 1861–62 tour and the contemporary debate over Australia’s national identity which it provoked, assumes great importance,” argues Frost. “The two main daily Melbourne newspapers (the Age and Argus) and a weekly sports paper (Bell’s Life), all gave the tour extensive coverage and were widely read amongst a highly literate population. Interestingly, despite being on opposite political sides, the two dailies were fairly similar in the attitudes they expressed. In contrast little information is available from other sources….”

In many ways, the games played by the All England team in Australia were not on equal terms as far as the local Australian line-ups were concerned. As Frost explains: “The All England Eleven was the first international sporting team to tour Australia. They were not the best English team that could have been raised, but in terms of experience, far superior to their colonial opponents. All were professionals. Since 1848 professional touring teams had been successfully operating in England and the players who journeyed to Australia had many years’ experience of touring and playing. In contrast, the colonial players were weekend cricketers, mostly amateurs.”

The professional English cricketers had no idea what to expect in the colonies and may have been unsure about the nature of the response they would evoke once in Australia. They need not have worried. William Caffyn, one of the team members, was to remark: “Great demonstrations on our arriving in Melbourne, flags being hoisted on most of the ships in the harbour and a crowd of over 10,000 people gathered to welcome us as we came ashore.”

The players were feted by an open coach-top parade from the docks directly to their designated accommodation at the Royal Hotel on Bourke Street for a ceremonious reception. In the opinion of the Melbourne Herald: “there had been no welcome like it since the Athenians arrived in Corinth." The tourists, being referred to locally as HH Stephenson’s team, were to play a total of 14 games in Australia, including one game in Tasmania, only one of the matches being attributed first-class status. It must be mentioned here that the majority of the games were played against “odds” of XV, or XVIII, or even of XXII local opposition players. The first game of the tour had been scheduled for New Year’s Day of 1862 at Melbourne Cricket Ground.

In deference to their long sea voyage and the fact that the visitors were yet to find their land legs, a request from Stephenson to reduce the strength of the local team from 22 players to 15 was partially entertained, the local team being reduced to 18 men. In the compilation 200 Years of Australian Cricket, 1804 to 2004, meticulously compiled by Garrie Hutchinson from local mainstream and collateral news media, it is said that between 15,000 and 20,000 eager spectators had turned out on a very hot day to witness the first day of the historic game.

Cricket goes international in Australia

As reported, members of both teams had been supplied with distinctive and individually coloured ribbons for their sun-hats and sashes of the same colour. The scorecards had been printed in such a way that each player’s specific colour was shown on it for easy identification. The new grandstand of the MCG had reportedly been “packed”. “Billy” Caffyn bowled the first delivery in an England-Australia cricket game to the local stalwart James Bryant, an ex-Surrey player, now a publican and footballer and turning out for XVIII of Victoria. It is reported that a total of about 55,000 people had paid at the turnstiles to witness this first cricket contest between a team from the Home Country and a local turnout.

The game had run to 4 days and had included, among other diverse points of interest, the first balloon ascent ever made in Australia. In addition, one of the intervals in play was enlivened by the exhibition of an 8-foot model of the steamship Great Eastern. The encouraging aspect of the first game of the tour from the point of view of the sponsors Spiers and Pond was the fact that the takings from this one game alone had been enough to cover their expenses for the entire tour. The cup seemed to be running over with unexpected doubloons for the sponsors, as it were.

For the local press, never adverse to a bit of sensationalism, the tour proved to be a bonanza. Mr. William Josiah Summer Hammersley, the former Cambridge, Surrey, and MCC player, and by now a well-established contemporary Australian sports journalist reporting under the pseudonym “Longstop”, writing in his Victorian Cricketer’s Guide for 1861-62, even went so far as to refer to some of the games played as being “Test” matches, the first time in history that the term had been used in connection with cricket in the press. Hammersley was of the considered opinion that: “Of the thirteen (sic) matches, five only can be termed test matches; the three played at Melbourne, and the two played at Sydney.” The idea, however, did not catch on, primarily for two reasons: all the games were “odds” contests, and all the games were against local sides with no pretensions of being representative on a national basis.

Sir John Robertson, an outstanding, though at times controversial, land reformer and politician based in Sydney at the time, often referred to as ‘The Dictator’ by the Sydney Morning Herald, was to cause some adverse comment among political circles in Sydney in early 1862 by allowing the promoters Spiers and Pond to levy admission charges for one match between HH Stephenson’s XI and a local team at the Sydney Domain, later redeeming himself by directing them to also arrange for a free stand for his Parliamentarians to witness the games.

Replying to the generous reception accorded to the English cricketers in Sydney, skipper Stephenson was reported to have made the following comments on behalf of his team members: “English customs and English feelings were firmly implanted here; that the same love of manly sport, the same appreciation of fair play existed that prevails in England … Everything around us seems so thoroughly English that I could almost imagine we were still at home.”

The Englishmen played a 3-day game against XXII of Tasmania at Hobart from 21 Feb/1862. Local enthusiasm was very high for the game, and the local press reported an attendance of “about five thousand.” The visitors won the game by 4 wickets and Charles Lawrence was seen in a rather unusual role in the game, that of one of the umpires.

There was only one first-class match played on the tour, billed as Surrey v the World, at a time when only intercolonial games were being accorded first-class status in Australia. The English contingent was split up into two sections with all the six Surrey players being in one group. Four noted Victorian players then joined each of the two groups of English players. James Moore, a New South Wales player of note, joined the World team, while Fred Christy, an erstwhile Surrey man, teamed up with the Surrey contingent to form two teams and to fill up the numbers.

The match was played at the MCG over 1st, 3rd, and 4th March, 1862, although the game had originally been billed as a timeless one. The crowd attendance over the 3 days was estimated to have been 4,500, 2,500, and 1,000 respectively, giving a total of 8,000 for the game. HH Stephenson himself (Surrey), and Tom Hearne (the World), led the two combating sides. The World team overwhelmed Surrey by 6 wickets.

Lawrence made his mark mainly as a bowler on the tour. Although he had only 1 wicket in the first-class match, he captured 51 more wickets on the tour from his 9 other games on the tour, with 5-wicket innings hauls in 4 of the games. Of his victims on the tour, 28 were bowled, and 18 were caught.

The tour turned out to be a greater financial success than Spiers and Pond had expected, with several figures between £ 11,000 and £ 14,000 in profits being quoted by different sections of the media. This amount was later to be invested in Railway refreshment rooms in England and in the Criterion Hotel of London. From the point of view of the tourists, the icing on the cake was the bonus of 100 sovereigns per head over and above the agreed upon amount of £150 per man.

For Australian cricket, the first ever English tour provided an enormous boost to local cricket. The local press had reported that an offer of an additional £1,200 that had been made to the visiting team by the sponsors to extend their stay by a further month. The offer had been declined on the grounds of other commitments, principally, the beginning of the 1862 English cricket season, all of them being professional cricketers, for whom cricket was their means of livelihood.