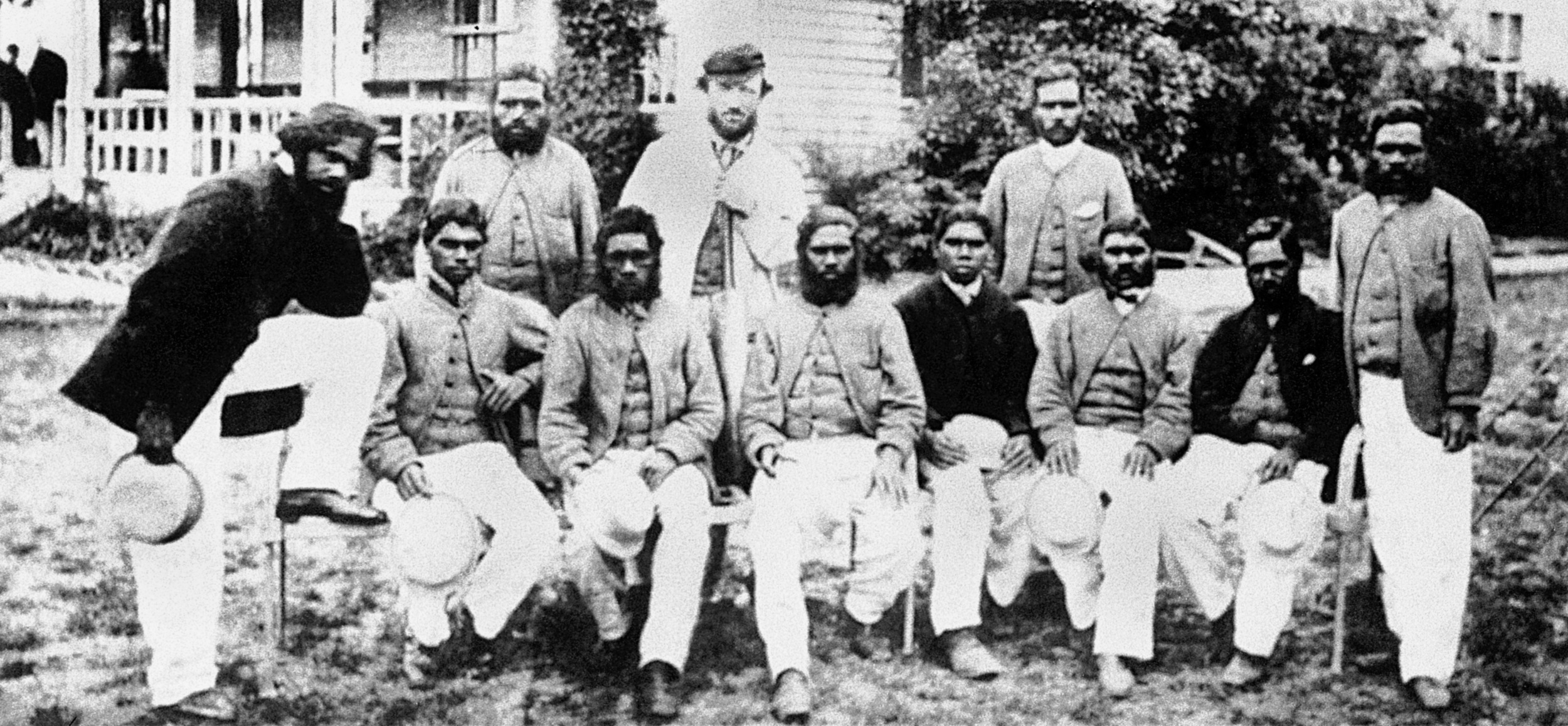

Charles Lawrence - photo courtesy Wikimedia commons

The epochal first ever Australian cricket tour to England remains one of the most curious tale of sporting relations. In this series, Pradip Dhole traces the journey and deeds of the Aboriginal cricketers, which remain surprising even after a century and half, and also relates the story behind the men who made this incredible venture possible.

“Saturday, the 23rd of May, 1868.

The Aboriginal black cricketers are veritable representatives of a race unknown to us until the days of Captain Cook, and a race that is fast disappearing from the earth. If anything will save them it will perhaps be the cricket ball. Other measures have been tried and failed. The cricket ball has made men of them at last.”

- Bell’s Life, quoted by Ed Hillyer in his book The Clay Dreaming.

The narrative begins on a very warm and wet Saturday afternoon of May 23, 1868 in the upstairs lounge of the Bear Inn of Town Malling, a quiet backwater just west of Maidstone, Kent, the first base for the team of indigenous Australian cricketers on the very first cricket, or indeed, any sporting tour of England by any Australian sporting team.

Of the three gentlemen present, all in full formal dress attire, a very uncomfortable dress code for such a close and humid day, one particular member appeared to be in a state of high mental agitation as he paced the length of the lounge back and forth with impatience and frustration written clearly on his furrowed brows. Charles Lawrence, the English skipper and impresario of the visiting team appeared to be lost in thought, with very good reason.

The vessel conveying the team to England had berthed at Gravesend on Wednesday, 13 May/1868, and the first cricket match of the tour was to be played at The Oval from 25 May/1868. Yet, there hardly seemed to be any coverage about the historic tour in the local newspapers. The local media could, perhaps, not be blamed in this respect, as the United Kingdom had been caught up in the frenzy of the General Elections of 1868 at the time, the first such exercise after the promulgation of the Reform Act of 1867. More than a million votes had been cast, about triple the number from the last General Election of 1865, and the great jousting between Gladstone, champion of the Liberals, and Disraeli, the Conservative candidate, was the main topic of discussion in news journals across the length and breadth of the land.

The Sporting Life of May 16, 1868 had been guarded in their report about the advent of the dark-skinned Antipodean visitors, as follows: “They are the first native Australians to have visited this country on such a novel expedition, but it must not be inferred that they are savages; on the contrary … They are perfectly civilized, having been brought up in the bush to agricultural pursuits … With respect to their prowess as cricketers — that will be conclusively determined by their first public match.” The response to such reports in the English media of the advent of the team of indigenous Australian cricketers to England had been lukewarm at best till date.

Although the tour management had taken great trouble to involve some well-known journalists from the leading and influential London papers in the preparations of the forthcoming event, there was scarcely any mention of the approaching cricket game in the press reports. The tour committee was in desperate need of some favourable publicity for the event so as to attract a reasonable turnout at the ground on the historic occasion. Instead, The London Illustrated News of the day, quoting from The Australian Mail, sported the screaming headline: “Attempt to Assassinate the Duke of Edinburgh.” Lawrence recalled the Duke having favoured the indigenous cricketers at practice in Sydney with a gracious royal visit shortly prior to their departure for the current pioneering tour.

There was a sense of trepidation among the three gentlemen present in the lounge, skipper Lawrence himself, William Hayman, the Manager of the team, and the latter’s brother-in-law, William South Norton, a British resident. Although they were aware of the unfortunate incident, having received the news on the boat coming over to England, the excited headlines in the local newspapers so close to their debut match on English soil seemed to be a portent of the proverbial spanner in the works for the enterprise.

The fear in their minds revolved around an event that had taken place on 12 Mar/1868 during a picnic party at the Sydney suburb of Clontarf in far-away Australia, with the royal personage in courteous and benevolent attendance, and had involved an attempt on the life of the second son of Victoria Regina, Alfred Ernest Albert, by a mentally deranged Irishman called Henry James O’Farrell. The tour think-tank was worried that the fall-out of the incident might affect the exotic appeal of the indigenous cricketers under their care while on tour in a detrimental manner. Indeed, there now appeared to be a distinct possibility of the tour being adversely affected, or even curtailed, partly or in its entirety, an eventuality that would be a financial disaster for the backers of the tour.

There was a polite knock on the door, and the proprietor of the establishment, Mr. Longhurst, was seen at the entrance to the lounge bearing a copy of the day’s Sporting Life. To Charles Lawrence, it was as if he was receiving manna from heaven. Pouncing on the paper, he began to read out the main news headlines: “Arrival of the Black Cricketers”, and “no arrival has been anticipated with so much curiosity and interest as that of the Black Cricketers from Australia.”

Urged on by his companions, Lawrence began to read excerpts from the paper aloud: “Monday in the Derby week (May 25) is to witness their debut in London.” The news bulletin continued as follows: “arrangements have been made for them to play their first match against Eleven Gentlemen of the Surrey Club, at The Oval, on May 25 and 26; and on the Thursday after the Derby, they will go through a series of athletic exercises on the Surrey ground.” There was a huge sense of relief in the room, for here was official confirmation for the general public about the unprecedented sporting spectacle that Londoners were about to witness in two days’ time.

The present story has its roots in the involvement of two white men who were to play major roles in bringing the remarkably pioneering endeavour to fruition. Their individual efforts at various times would lead to the accomplishment of one of the most significant ventures in international cricket, not only from the purely historical perspective, but also for its impact on the greatest rivalry in world cricket, a rivalry that is as intense and competitive now as it had been when the saga had unfolded in the early 1860s.

Let us pause at this point of the narrative to collect our thoughts and to take a time and space flashback, and to consider the first of the threads referred to above.

Early days of Lawrence

The Domesday Book records a certain “Hogesdon”, an Anglo-Saxon term denoting a farm or “fortified enclosure” belonging to one Hoch or Hocq. In later years, the settlement came be known as Hoxton, and was incorporated as a rural section in the Shoreditch parish. In the year 1826, the area was able to boast of a parish church of its own, dedicated to St. John the Baptist. In an intriguing turn of historical events, the township of Hoxton was to acquire a degree of notoriety early in the 17th century, becoming associated with the infamous Gunpowder Plot of Oct, 1605 when one of the perpetrators of the plot, Francis Tresham, was to be arrested from his home in Hoxton after the failure of the ignominious plot.

On Dec 16, 1828, however, a rather more pleasant event occurred at Hoxton, East London, with the birth of a son in the local Lawrence household. Christened Charles, the child grew up in the parish of Merton, Surrey, mentioned in the Doomsday Book of 1086 as Mereton, the most populated community of the area. According to a brief biography written by Edward Liddle and published in 2007 in the website of CricketEurope, subtitled Irish Cricket History, the young Charles attended the local village school at Merton, along with several other boys of comparable age. It appears that the lure of cricket had ensnared the young lad from a relatively early age.

In an autobiographical study that he had begun late in his life but had, regretfully, abandoned later, Charles Lawrence remarks that he had been superior to his playmates in his cricketing skills, and makes the modest assertion: “I was regarded by my schoolmates as a wonderful cricketer.” Some of the local cricketers, all older than him, would often ask him to bowl to them. There was an instance after his schooldays were over when he is known to have combined with his friend Tom Sharman, later to become a noted bowler for Surrey, in dismissing the entire Crayford team for 70 runs in their match against Merton.

One of the more memorable facets of his school cricketing days was his adulation of the great batsman of yester years, Fuller Pilch. It is said that the young Lawrence had once played truant from school and braved parental censure by walking over 12 miles to The Oval to see the great man bat. Alas, Pilch had chosen that day of all days for one of his rare failures and had been dismissed very early in his innings to the intense disappointment of the adoring lad.

Lawrence gradually developed into a very useful cricketer. According to Liddle, the “slightly built and bearded man” became a more than useful right-hand middle order batsman, though known to move up the order if the situation warranted it. Among his contemporaries, his style was considered to be “sound but somewhat defensive.” His main expertise, however, was in his bowling. He seems to have begun his bowling career as an accurate lob bowler. He is then reported to have been, at different stages of his life and career, a fast right-arm round-arm bowler in his youth, a more sedate medium-pacer in later life, returning to the lob bowling that he had begun his career with, a genre that was deadly accurate and which would very often catch the batsman unawares. This incredibly gifted cricketer has also been known to have occasionally kept wickets with great distinction. In short, Charles Lawrence could easily lay claim to being one of the most complete all-rounders of the fledgling nineteenth century cricket scene.

Despite being blessed with so many cricketing skills as a player, Charles Lawrence is chiefly remembered in history as being an outstanding coach, and being “profoundly” instrumental in the development of the game both in Australia and in Ireland, where he is known to have played a lot of his early cricket. Indeed, Ashley Mallett, the Australian off-break bowler and well-known scholar of cricket history, author of such books as The Black Lords of Summer, and Lord’s Dreaming about the 1868 Aboriginal cricket tour to England, has honoured Charles Lawrence with the honorific title of Father of Australian Cricket. Noted sports columnists Gerard Siggins and Jim Fitzgerald are of the opinion that: “The same tribute should also be paid (to Lawrence) by Irish cricket” for his significant contribution to the early development and organisation of cricket in the Emerald Isle.

Running away for the game

At a relatively young age, he was pressed into service as an apprentice to a print cutter in Merton in the hope that he would later follow in his father’s early footsteps in the same profession. Around this time, his parents were to be found living in Scotland. Young Lawrence was not interested in learning the job of a print cutter. He ran away and fled to join his parents in Scotland, where his father had, in the meantime, become the manager of a printing concern. Charles soon realised that his passion lay with cricket and threatened to run away to sea if he was not allowed to pursue his love for the game. Perforce, his parents agreed to his playing cricket in Perth, a city in central Scotland, on the banks of the River Tay. The condition was that he was to return to his apprenticeship at Merton at the end of the cricket season. The cricketing Gods, however, willed otherwise.

In the revised and updated edition of The Penguin History of Australian Cricket, authors Chris Harte and Dr Bernard Whimpress inform us that Charles Lawrence is known to have launched his career as a professional cricketer in 1846, barely past his 17th year, by accepting an assignment as cricket coach of Perth Cricket Club of Scotland. Displaying remarkable fidelity for one so young, he was to be with Perth Cricket Club till the 1850 season, despite receiving lucrative offers from rival clubs.

The earliest documentation of the cricket career of Charles Lawrence begins with the “odds” match played at Edinburgh between XXII of Scotland and the All England XI, founded by William Clarke in 1846, the second-class match being played over 7th, 8th, and 9th May, 1849 at Edinburgh. Lawrence was then in his 21st year. The visiting All England Eleven, on their first ever visit to Scotland, won the game by 161 runs. The undoubted hero of the match, however, was young Charles Lawrence. Although his contributions with the bat were modest and self-effacing in the extreme – 3 and 0 to be precise, he picked up 3 wickets in the AEE 1st innings for 59 runs. He then came into his own in the 2nd innings, capturing all 10 AEE wickets for 53 runs, and thus achieving match figures of 13/112. This was the first instance of any bowler capturing all 10 wickets in an innings in the history of cricket in Scotland.

Lawrence’s victims included William Clarke himself, John Wisden, George Parr, Nicholas Felix, and Alfred Mynn, among others, a veritable galaxy of the cricketing talent of contemporary England. It is reported that he had clean bowled Felix (18) with a “shooter”, knocking all three stumps out of the ground. An interesting sidelight to the AEE 2nd innings was the fact that skipper William Clarke had carried his bat through the innings without opening his account in a team score of 132 all out, surely one of the more bizarre happenings in the history of chronicled cricket.

Wedding bells rang for Charles Lawrence in 1850 when he married Anne Elizabeth Watts. Settling into a life of domestic bliss, they raised a family of a son and two daughters, with all three children being born in Dublin. He set up a business as the proprietor of a sports goods and tobacconist’s shop in Glasgow, while also turning out for the local Caledonian Cricket Club as a professional cricketer. This business venture, however, did not last for long, and the young couple made their way to London soon. To sustain his young family, he accepted appointments in a printing works and later spent some time as an employee of the local railways. Cricket, however, was always his passion.

It is fair to say that Fate lent a helping hand in bringing Lawrence in contact with William Clarke in England around this time, and the young railway official succeeded in obtaining an appointment as the coach of the Phoenix Cricket Club of Dublin in 1851 through the good graces and endorsement of Clarke. It was to be an inspired move on the part of the young Lawrence and a boon to Irish cricket.

A pamphlet of Cricket Ireland tells us that the Phoenix Club had been one of the oldest established cricket clubs in Ireland. It was in the year 1792 that the first major cricket match had been played in Ireland, between the Military of Ireland and the Gentlemen of Ireland at Phoenix Park, Dublin, the home ground of the Phoenix Cricket Club. By the mid-1850s, cricket had grown to be the most popular game in Ireland, and the sport with the most dedicated followers. One of the main reasons for the game’s popularity was the fact that this was a game completely free of any class consciousness or discrimination.

When Lawrence joined Phoenix as a professional cricketer in May/1851, he was about 6 months shy of his 23rd year. His influence was very soon apparent when he toured the North of England with the Phoenix Club in 1852 and played a single day game against Liverpool at Liverpool on 28 Aug/1852. Phoenix won the game quite comprehensively by 10 wickets, with Lawrence capturing 7 wickets in the home 1st innings, 6 of his victims being bowled. He made a contribution with the bat as well, being the joint top scorer for his team with 16 runs in a total of 87 all out. Lawrence then captured another 5 wickets in the Liverpool 2nd innings, all his victims being bowled, thus completing a commanding performance for his Irish team.

In the same fixture of 2 Aug/1854, Phoenix won the game by an innings and 46 runs, Lawrence scored 68, opening the batting, in a team total of 200 all out. He then took 5 wickets in each innings, 9 of his 10 victims being bowled and one man being out lbw. His performances gradually began to instil a sense of self-belief among the Irish cricketers and to motivate them to go from strength to strength.

It was rather late in the 1854 cricket season that Charles Lawrence reached another significant milestone of his cricketing career, making his first-class debut playing for Surrey in an “away” match against Sussex at Hove from 28 Sep/1854, alongside James Southerton, the only other debutant in the game. The scheduled 3-day match was over on the second day with a 10-wicket victory for Surrey. Lawrence contributed his mite to the victory by dismissing John Lillywhite, son of the legendary William Lillywhite, known respectfully in cricket history as “The Nonpareil”, in both innings of the game, for 12, and 10, these being his only 2 wickets in the match. Opening the bating in the Surrey 1st innings, he also scored a solid 22 in a team total of 170 all out.

With time, Lawrence succeeded in boosting the confidence of the local Irish cricketers to a sufficient extent for them to form a team calling themselves the United Ireland XI, formed along the lines of the All England XI, and the United All England XI. Charles Lawrence acted as the Secretary and the skipper of the newly formed Irish team. The United Ireland XI played their first documented match against XXII of Dublin at Phoenix Park in a 3-day game from 11 Aug/1856. The United Ireland XI won the game by 2 wickets after skipper Lawrence captured 13 and 11 wickets respectively in the two innings in which the XXII of Dublin batted, adding a further feather to his cricket cap.

There was a momentous occasion for the Irish national cricket team in May/1858 when they began a 2-day game against the might of the MCC at Lord’s, their first experience of the majesty of the iconic venue. The historical archives at Lord’s establish the fact that this was the first time that any cricket team from Ireland had ever made an overseas tour. Played over 17 and 18 May, the Irish team created their own slice of cricket history by winning the fixture by an innings and 10 runs.

The Lord’s archive, named Ireland at Lord’s goes on to say: “Ireland’s victory was largely thanks to the outstanding performance of Charles Lawrence, who took 8-32 in MCC’s first innings as they collapsed to 53 all out. He then captured another 4 wickets (for 25 runs) in the second innings as Ireland won the match within two days.” Irish cricket, then, had come of age in a spectacular fashion under the gentle tutelage of Charles Lawrence.

The association between Scotland and Lawrence was to stretch from 1849 to 1858. His last game under Scottish colours was for XXII of Scotland against the United England XI, and was a 3-day affair played at Glasgow from 23 Sep/1858. The visitors won the game by 8 wickets, whilst Lawrence scored 25 out of a 1st innings total of 78 all out, and captured 3 wickets in the visitors’1st innings. One chapter of his eventful career had now been closed.

One of his blue-blooded benefactors was the aristocratic bachelor, George William Frederick Howard, the 7th Earl of Carlisle, the eldest son of the 6th Earl. The 7th Earl was appointed the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland in 1855 and held the post till 1859. Taking a keen interest in cricket, the 7th Earl employed Charles Lawrence during his tenure and entrusted him with the task of laying out a proper cricket ground in the Vice Regal Lodge. Although the ground was never in very frequent use, some interesting matches are known to have been played on it, the last of them being played by a local team against I Zingari in 1906.

The Vice Regal Ground was witness to one of the great bowling feats of Lawrence when he represented the United Ireland XI against the visiting I Zingari team in Sep/1860. Although the visitors won the second-class fixture by 4 wickets, Lawrence captured 8 wickets in a 1st innings team total of 63 all out.

It is estimated that in all games under Irish colours, including 5 “odds” games involving more than 11 players in the opposing team, Lawrence captured 98 wickets, with 5 or more wickets in an innings on 11 occasions, and took 10 or more wickets in 5 games. In addition, he scored 254 runs in all for his various Irish teams. No wonder that he is still revered among Irish cricket enthusiasts till this day.