February 8, 1990. In the midst of combustible political situation, the very last rebel ‘Test’ got underway in Johannesburg between South Africa and Mike Gatting’s England XI. Arunabha Sengupta looks at how the game was played amidst protests, demonstrations, massive country-wide changes and the release of Nelson Mandela.

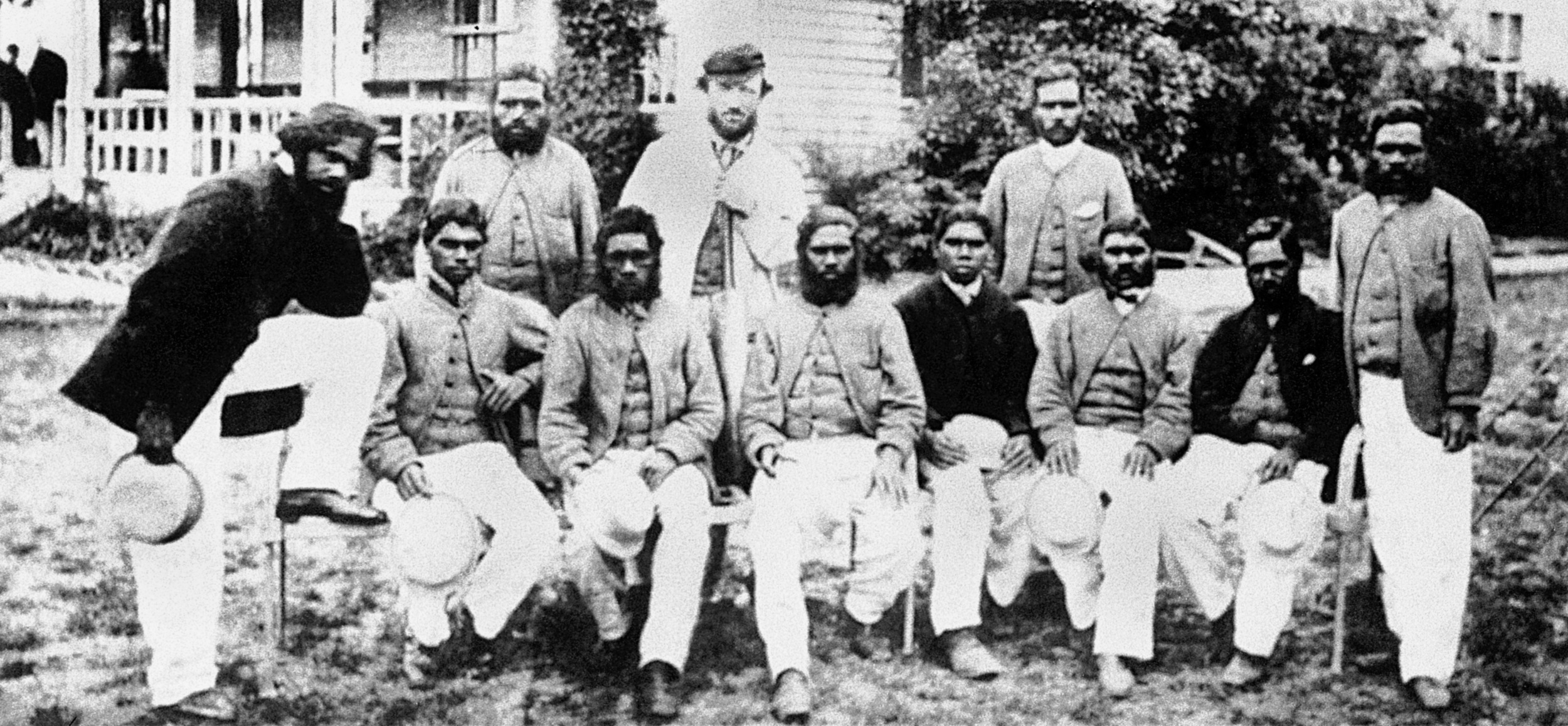

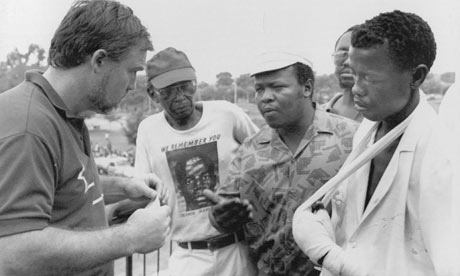

England skipper Mike Gatting - with anti-apartheid demonstrators

On the field, two and a half hours were lost to rain. During the remaining part of the day, the cricket was at best mediocre. After all, how much could be expected of a patchwork side of ordinary cricketers boosted by a couple of big stars?

However, the day went down as one of the most significant in the history of the game — although seldom recounted as such.

This was the day that saw the start of the last of the rebel ‘Test’ matches in South Africa.

In the wrong place at the wrong time

According to Ian Wooldridge, Mike Gatting found himself in the wrong place at the wrong time.

Captain of the seventh rebel team to tour the forbidden land of South Africa between 1982 and 1990, he found himself in the very hotbed of a political turmoil that he neither claimed to understand nor had any illusion of being able to control.

It had taken quite some disenchantment for this committed England batsman to sign the dotted line. After all, in 1989, for the first time the International Cricket Council (ICC) had formalised the rule that participation in South Africa through playing, coaching or administration would result in a ban of three to five years depending on the age and nature of contact. The ad-hoc handing out of suspensions had been brought to an end. Unlike earlier trespassers into the tabooed cricketing nation, players now knew fully well what they would be risking.

Yet, one of England’s proudest cricketers and former captain agreed to go there. There were reasons.

The 1980s had been eventful for Gatting. West Indies had blackwashed England and Malcolm Marshall had broken his nose. He had returned to the battleground with a modified nasal structure, only to break his thumb.

He had captained England with distinction in 1986-87 to retain the Ashes against a weakfish Australian side. And then, under his leadership, the team had reached the World Cup final in India.

And then things had fallen apart. In the final, he was out to an irresponsible reverse-sweep — one of the triggers of the English defeat to Australia. Following that, he had got involved in the infamous spat with umpire Shakoor Rana in Pakistan.

Finally, when West Indies had visited in 1988, he had published a book detailing the Rana controversy — and the Test and County Cricket Board (TCCB) had not been amused. After a drawn first Test at Trent Bridge, a tabloid newspaper had caught Gatting in a sting, taking a waitress to his hotel room. As a result of this rather bizarre issue, he was sacked as skipper.

The new chairman of selectors Ted Dexter did want him back at the helm for the 1989 Ashes and informed him as much in private. But, his decision was vetoed in the selection meeting and TCCB reverted to David Gower.

This final snub was a bit too much for Gatting to endure.

Almost at the same time, Ali Bacher, chief of South African Cricket Union, (SCU) visited London to champion the cause of his country’s cricket at the Wisden dinner. Amidst all the talk of racial integration taking place in South African cricket, Bacher was busy recruiting an English team to play yet another of the rebel series. Decent Test caps such as Chris Broad, Bill Athey, Richard Ellison, Tim Robinson, Matthew Maynard, Paul Jarvis and John Emburey were lured in. And the biggest surprise was the last moment of Gatting.

The Middlesex batsman’s travails started almost immediately. Daily Mirror shouted “Traitors!”,Daily Mail screamed “Blood Money Cricket Storm”, The Times warned of “Rebel Threat to British Sport”.

Gatting insisted, “I’m no traitor. I do not see myself as a traitor because I am going off to earn a living by playing cricket in South Africa. I think I’ve been a loyal person. I’ve given a lot of my life to cricket. It’s time for me to put my family first.” As Daily Mirror declared “Judas would have been proud of them all”, Gatting insisted that he would meet any protester in South Africa.

This pledge would place him in several unprecedented situations.

Changes in the air

From the start, Gatting and the England team came face-to-face with circumstances that the previous rebel teams had been shielded from with scrupulous care.

Before 1989, protests in South Africa had been decreed illegal. Agitations had taken place against the tours of Graham Gooch’s team in 1982, and the sides of Lawrence Rowe and Kim Hughes down the years. But, the demonstrations had mostly been far away from the eyes of the players. The apartheid police machinery had cracked down on any demonstration that had tried to get close to the players or the cricketing action. The players had moved around in the white South African bubble, with best facilities and comfort. The major protests they had encountered had been back home and around the world. Their South African experiences had been largely peaceful.

However, in January 1989, President PW Botha suffered a stroke. His successor, FW De Klerk, a staunch pro-apartheid man for ages, surprised all with a series of reforms. In September 1989, the prohibition on political protests was lifted. And the English cricketers felt the full brunt of it.

Violent protests and police action were features of the tour. The first tour match had to be moved from East London to Kimberley to escape the African National Congress (ANC) agitators. But, a mass demonstration nevertheless took place. The protestors had not availed the necessary permit required for such demonstrations. As the police were about to resort to force, a concerned Ali Bacher himself made phone calls and arranged for the necessary permit on behalf of the demonstrators.

The black workers even refused to serve the English cricketers in restaurants. The team had to be cordoned off from the multi-racial dining rooms and had to use the self-service buffet. On one occasion, Gatting even went into the kitchen and cooked steaks himself.

To keep his promise to petitioners, Gatting met young anti-tour leaders during the last day of the match against South African Universities. While handing over the paper, one petitioner called John Sogoneco removed his short to reveal buckshot wounds from police action. A stunned Gatting responded that it was not something he could help him with.

As they headed for their last match before the ‘Tests’, De Klerk lifted restrictions on the ANC and a couple of other parties. He also declared that Nelson Mandela would be released from prison in very near future.

The implications were huge. And amidst such a tornado of changes, the tour — seen as pro-apartheid — met more and more obstacles.

At Pietermaritzbug, Gating was requested by petitioners to walk through a sea of demonstrators — most of them chanting ‘Gatting go home’, get on a podium and receive the piece of paper outlining their demands. Against frantic pleas not to go ahead with this, Gatting defiantly did as he was asked. Walking back to his mates, he continued on his way back to the pavilion, picked up his hat and marched into the field to continue the game, calling his men to join him. He had been naïve, but few could question his bravery.

The final ‘Test’

As the first ‘Test’ started in Johannesburg on February 8, hundreds of black spectators sat on the stands. They had been gathered by a group called ‘Freedom in Sport’, with promises of work at the stadium. The intent was to ensure that the television cameras captured the images of a multi-racial audience.

Permits of conducting protests near the ground were refused and tear gas was used on the 2000 demonstrators who had assembled.

In the ground, the pressure built up on both the teams was intense. After the infuriating rain delay, the young duo of Allan Donald and Richard Snell bowled at the Englishmen on a dreadful pitch.

Athey fell to the pace of Donald, but Broad and Robinson stitched together a slow, steady partnership. The second wicket stand was worth 81 before Brian McMillan got rid of both the batsmen in quick succession. England XI ended the day at 111 for three, with Gatting and Alan Wells at the crease.

That evening and in the next day’s papers Donald and Snell were castigated for being unable to take wickets on a helpful track. The following morning they ran in with lots to prove to their critics. The rest of the England batting was blown away for just 43 runs.

For England, Jarvis, Ellison and Foster returned the compliment in kind, and soon South Africa were struggling at 40 for four. The formidable top order of captain Jimmy Cook, Henry Fotheringham, Kepler Wessels and Peter Kirsten all fell for low scores. But, all-rounder Adrian Kuiper flogged the bowling for 84 and the innings ended on the third morning at 203.

As a crowd of 10,000 flocked in to the stands, the England XI meekly surrendered to Donald, Snell and McMillan. They totalled just 122 and left the hosts to score a paltry76 to win. South Africa won by seven wickets.

Nelson Mandela was released the morning after the conclusion of the ‘Test’.

What followed?

The second ‘Test’ was supposed to be held in Cape Town. However, an explosion near the ground ensured that the fixture was cancelled. The Mass Democratic Movement declared: “If Gatting can make his own food, then he ought to be quite capable of making his way back to London in an emergency situation.”

The match at Johannesburg remained the 19th and last ever rebel ‘Test’.

The original plan was to play seven One Day matches. However, the combustible circumstances forced the organisers to bring the number of games down to four. In farcical circumstances which involved floodlight failure, the hosts triumphed 3-1.

As Gatting and his men hurried out of the country, Frank Keating summed up the situation by writing, “No more inglorious, downright disgraced and discredited team of sportsmen wearing the badge of ‘England’ can ever have returned through customs with such nothingness to declare.”

Brief scores:

England XI 156 (Chris Broad 48; Allan Donald 4 for 30, Richard Snell 4 for 38) and 122 (Allan Donald 4 for 29) lost to South Africa 203 (Adrian Kuiper 84; Richard Ellison 4 for 41) and 76 for 3 by 7 wickets