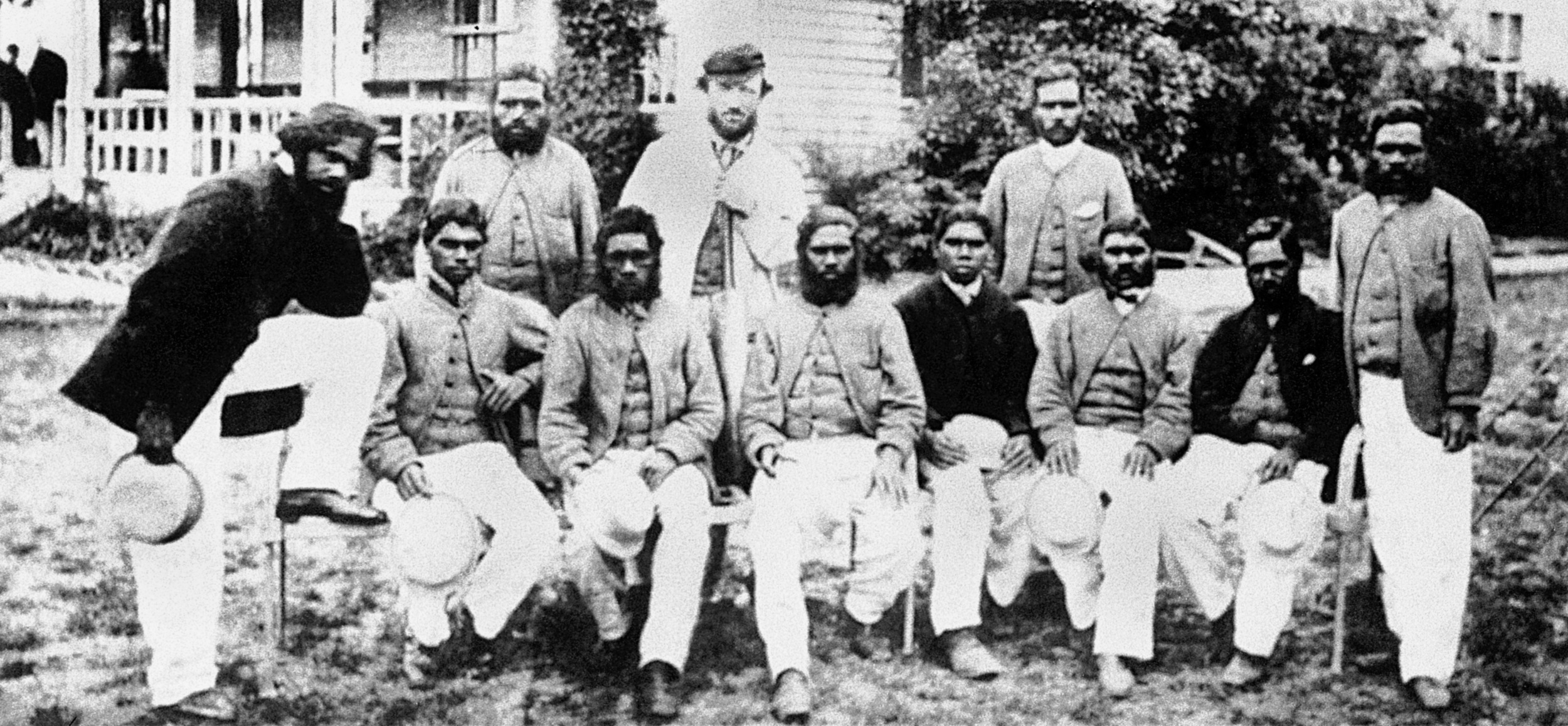

“The greatest team photo in Australian sporting history.”

Tom Wills and his team of Aboriginal cricketers at the MCG, 1866

The epochal first ever Australian cricket tour to England remains one of the most curious tale of sporting relations. In this series, Pradip Dhole traces the journey and deeds of the Aboriginal cricketers, which remain surprising even after a century and half, and also relates the story behind the men who made this incredible venture possible.

Part 1

Murder and Mayhem

The first leg of the journey was accomplished by steamer to Brisbane from Jan/1861 onwards. This was followed by an overland trek lasting about 8 months through the Queensland outback. It was a long and arduous journey through unfamiliar territory. Food being in inadequate supply for the men and the animals, Tom, a crack shot, spent much of his time on the trek in hunting local fauna to replenish their depleting stock of food, always conscious of the inquisitive eyes of the local indigenous population being upon them. The vanguard of the trekking party, including Horatio, his followers, and part of their livestock, arrived at Cullin-la-Ringo, in the Kairi Aboriginal heartland, in early October, 1861.

Tragedy struck the tented establishment of Horatio Wills on the afternoon of 17 Oct, 1861, about 2 weeks after the arrival of the trekkers at Cullin-la-Ringo. Horatio and 18 other members of the trekking party were brutally murdered by the local Aboriginals. It turned out to be the most savage massacre of white settlers by the Aboriginal population in Australian history. It was later learnt that Tom, accompanied by two stockmen, Jim Baker, and Bill Albury, had not been present at the Cullin-la-Ringo establishment at the time, having back-tracked to Albinia Downs to retrieve supplies they had left behind en route to the new settlement. By the time Tom reached the site, the ominous sight of smoke rising from the devastated area spoke of the extent of the tragedy that had struck during his absence.

A pamphlet of the Queensland Historical Atlas sheds some light on the possible reason behind the gory carnage. Discontent had been brewing among the local indigenous population from events arising about 50 miles further up-river from Cullin-la-Ringo earlier in 1861 when some white graziers had been poisoning the water holes of the Kairi indigenous population and shooting the local Aboriginals indiscriminately. The name of a local white settler, Jesse Gregson, had been hinted at in this connection. At the same time, the Native Mounted Police “were being encouraged to forcibly evict Aboriginal people from station and river camps.” The last-mentioned act on the part of the white establishment was seen by the local natives as being unforgivable an act of betrayal.

It was further conjectured that it had actually been Jesse Gregson, not Horatio Wills, that had been the intended target of the enraged Aboriginals, and that it had been a case of mistaken identity that had caused the demise of Horatio Wills. Indeed, in his Doctoral dissertation entitled In From the Cold – A Nineteenth Century Sporting Hero, and submitted to Victoria University in Sep/2008, author Gregory Mark de Moore quotes a younger brother of Tom, Cedric Wills, who had lived on the Queensland property of Cullin-la-Ringo for many years, as saying in later years that: “If the truth is ever known, you will find that it was through Gregson shooting those blacks; that was the cause of the murder.”

Under the circumstances, the Cullin-la-Ringo tragedy was seen as an act of reprisal on the part of the local Aboriginal population, with their simmering sense of being persecuted in their own land, and their resultant discontent surfacing at last. Retribution from the white population was swift and ruthless and about 200 of the native population were shot down in the aftermath of the event of 17 Oct/1861. The whole incident was reported in great detail over two and a half columns of print on page 7 of The Sydney Morning Herald of 16 Nov, 1861 under the heading “The Wills’ Tragedy (By an Eye-Witness).” Unfortunate as it was, the event turned out to be an event of enormous importance in the holistic early history of the Antipodean British Colony that was gradually being settled in by white people after the initial stock of hardened British convicts had been deported there.

Tom’s younger brothers were known to have had their schooling in Germany, and were known not to have been present at Cullin-la-Ringo on the fateful day, nor, it would appear, had any of the womenfolk of the family been present there on the day. Wills spent the next two years at the estate, with his mind in a state of constant turmoil and his psyche pathologically, perhaps irrevocably, scarred from the constant skirmishes between the white settlers and members of the native Aboriginal population.

Reports of gross financial irregularities in connection with the running of the Cullin-la-Ringo estate began to surface one by one. When questioned by senior members of the family and the legal executors of the property, Wills was unable to offer any logical explanation for the lapses. Perforce, Wills had to leave the management of the new property to his brother Cedric and return to Melbourne in 1864.

Wills and continuation of Cricket

There is no documentation of any level of cricket played by Wills between the match against NSW at Melbourne from Feb 2,1860 and the clash between the same teams at Sydney from 5 Feb/1863. The personal misfortune of October, 1861 prevented his participation in any of the games against the 1861/62 English visitors. With the arrival of George Parr’s 1863-64 English visitors in Australia, and after having become implicated with some financial irregularities pertaining to the Cullin-la-Ringo property, Wills decided to accompany Parr’s team on their detour to New Zealand, where he played 2 minor games against the Englishmen touring New Zealand.

Returning to Melbourne in 1864, he took up residence in the family property at Geelong. Having acquired a reputation of being a libertine, his earlier engagement to Julie Anderson, daughter of a respected family friend, fell through around this time, his drinking habits and his wandering eye for the fairer sex being largely to blame for this. During this phase of his life, Wills’ relations with an already married woman named Sarah Theresa Barbour, considered at the time to have been a “woman of easy virtue”, gradually estranged him from his immediate family, his mother and siblings slowly distancing themselves from him. Wills became more and more isolated within his own family, and increasingly addicted to alcohol. He began to experience nightmares from flashbacks of the 1861 Cullin-la-Ringo incident. He also developed psychiatric problems arising out of the same sad event in the family. Amazingly, despite his personal problems, his cricketing skills did not abandon him.

The clash between Victoria and NSW at Melbourne from Boxing Day of 1865 saw Wills achieve another feather in his much-decorated cap. Winning the toss, NSW batted first and were dismissed for 122, skipper Wills capturing 4/33, and bringing up his 100th first-class wicket in the process. Batting at # 10, Wills then scored 58 out of a team total of 285 all out, the total scored in 265 minutes. This was the highest team total in Australian first-class cricket till that time, and Wills’ 58 was to be the first recorded individual first-class fifty in Australian cricket history. Dismissing NSW for 143 in their 2nd knock, Victoria won the match by an innings and 20 runs. Despite the decisive victory, there was general discontent with Wills’ bowling action, the popular notion being that he was in the habit of ‘throwing” some of his quicker deliveries.

The issue of the Australian Gold Rush of the early 1850s seems to be a recurrent theme of this narrative. Scholars of the local history of the times are of the opinion that several members of the white “settler” population of Australia had abandoned their pastoral pursuits temporarily to join the “diggers” in the misguided hope of quick riches. Disillusion soon forced many young hopefuls back to their pastoral pursuits. In the meantime, more and more of the indigenous population were employed on the farms in the far-lying outstations to look after the farm animals and to assist in the actual farm work. Coming into close contact with the white population, they were gradually beginning to pick up some of the habits and pursuits of the white settlers. One of these pursuits was cricket.

Mixed Race Cricket

In an article entitled Black Social History – The Australian Black Cricket Team in England in 1868 – A Side Composed of Black Australians, dated Apr 17, 2014, author George Eleady-Cole of Liverpool asserts that: “From the early 1860s onwards, cricket matches between Aborigines and European settlers had been played on the cattle stations of the Wimmera district in western Victoria, where many Aborigines worked as stockmen. The athletic skills of the Aborigines were so evident that a series of matches was eventually undertaken with the intention of forming the strongest-possible Aboriginal eleven.”

In their meticulously researched and updated Second Edition of the book Cricket Walkabout, authors John Mulvaney, Professor of Prehistory in the Faculty of Arts at the Australian National University, and Rex Harcourt, Research Librarian for the Melbourne Cricket Club at the MCG Library, portray a detailed picture of the involvement of indigenous Australians and their interaction with the white settlers of the post-Gold Rush era of Australian history.

According to Mulvaney and Harcourt: “Edenhope acquired a cricket club around this period (1864). With the All-England XI tours (of 1861/62 and 1863/64) stimulating bush imitators, no settlement seemed too remote to field a team.” With enthusiastic coaching from some of the white settlers, several “stations” of the Western Victoria region were soon able to field their own teams in which indigenous cricketers were seen playing alongside white pastoralists. Some of the more prominent local teams are listed below, from data presented by Mulvaney and Harcourt:

Station cricket had become so popular at this time that a game is reported to have been played in 1865 between a team consisting of Europeans and another comprising indigenous players exclusively. The game had been supposedly played on a rather “rough” level area near the Bringalbert woolshed. Members of the indigenous team had been selected from representatives of some of the stations listed above. The indigenous team had won the game, although the details of the game are not available now.

The indigenous cricketers having proved their worth, it was decided to garner the more promising of them for further coaching. Tom Hamilton of Bringalbert and William Hayman of Edenhope selected a core group of talented players who were then brought to Edenhope for further coaching and were encouraged to practice with the members of the Edenhope Club members on Saturdays. It was initially William Hayman who took upon himself the responsibility of coaching the group in the basic skills of cricket. These players were members of the Jardwadjali, Gunditjmara, and the Wotjobaluk tribes, and proved to be quick learners, all of them being blessed with a native keenness of eye and athleticism.

The Minutes Book of the Melbourne Cricket Club of 8 May/1866 contains, among others, the following entry: “It was agreed to allow R. Newbury to use the ground for two days during the month for (the) purpose of a match with the native black eleven.” This Rowland ‘Roley” Newbury, ostensibly ‘curator of the pavilion and ground’ and player at the Melbourne Cricket Ground, but in reality, the proprietor of the refreshment stalls of the ground, had submitted an application to the authorities of the famous Melbourne club seeking permission to stage a cricket match on the premises between the club members and the team of indigenous cricketers, offering the Club £ 25 for the privilege, and hoping for custom at his refreshments tent during the game. While altruism may well have been a factor in Newbury’s scheme, sceptics would believe that the monetary angle may have acted as a more powerful motivation for him.

Mulvaney and Harcourt are of the opinion that enthusiastic feedback from responsible white settlers of the region regarding the skills and general demeanour of the Aboriginal cricketers may have helped to sway the deliberations of the Club Committee favourably towards the application of Newbury. Of particular significance was the opinion of Hugh McLeod, who happened to be the local correspondent to the Victorian Board for the Protection of the Aborigines, and who was prepared to take responsibility for their welfare while in Melbourne. In the meantime, following the encouraging performance of the indigenous cricketers against the white settlers, William Hayman of Edenhope decided to send off some photographs of the team of indigenous cricketers to the Melbourne newspapers, mainly for publicity purposes, in Aug/1866.

The Australasian of 18 Aug, 1866 carries a quote from a letter written by William Hayman to Tom Wills, as follows: “… shall be happy to cooperate with you in arranging for the black cricketers’ visit to Melbourne. We have a cricket ground fenced in at the township of Edenhope and will muster the blacks there and pay their expenses whilst at cricket and provide them with the necessary material for playing and also with decent clothing for their visit to Melbourne”. This was followed later by the following notification: “Mr Wills has consented to go up to Lake Wallace to prepare the blacks for their first appearance in Melbourne … A month under Mr Wills’ tuition with him as their captain should give them every chance of making a good show in the cricket field.”

During his time with the Melbourne Cricket Club in the late 1850s, both as Secretary and captain of the Club, Tom Wills had made the acquaintance of Rowland Newbury, and around Nov/1866, being free and in need of money, and with no family ties to tie him down, his own family having largely disowned him by now, Tom had no hesitation in accepting the coaching assignment offered to him. He arrived at Edenhope in late Nov, 1866 to take up his challenging responsibility.

After several postponements of the event for various reasons, Newbury’s application was considered by the Club for a final time at their 15 Nov. 1866 meeting. The grand game at the MCG was ultimately slated for the Boxing Day of 1866. The Australasian, in their 29 Dec, 1866 edition, was to later remark: “The match originated through the MCC granting the use of their ground to Roland Newbury who has for many years been curator of the pavilion and the ground and whose uniform good conduct and attention to his duties entitled him to such a mark of approbation from the club.”

Time was at a premium for Tom Wills as he took up the task of coaching the team of Aboriginal cricketers preparing for their Melbourne game, his own phenomenal cricketing skills and his leadership qualities with first-class teams adding authority to his role as a mentor. Secret coaching sessions began at the practice ground at Lake Wallace in Edenhope. While hitting the ball hard came quite naturally to the pupils, given their keen eyesight and quick reflexes, instilling some semblance of technique took a while. In the bowling department, the native cricketers had originally favoured the under-arm mode, but were quick to adapt their technique to the round-arm style with good effect. Wills laid particular emphasis on the aspect of fielding. In all, Wills was to captain and coach his charges for about a year till 1867.

Gregory Mark de Moore quotes from a comment appearing in the Geelong Advertiser of 19 Nov. 1866 on the issue of the proposed “novel” match at the MCG: “This will be the most novel event that has ever been offered to the lovers of cricket. A white NSW native having 10 Victorian blackfellows in his company, will show civilized Britons how cricket ought to be played.” The presence of Tom Wills as captain and coach of the indigenous cricketers seems to have boosted the confidence of even the members of the Melbourne Cricket Club enough for this comment to be recorded in the Minutes Book: “We understand that Mr T. W. Wills is likely to go to Hamilton to coach the black fellows, and from the skill already exhibited by them, there is reason to believe they will shew very good cricket on the MCC ground ...”

The archives show a one-day game being played at the Melbourne Cricket Ground on 26 Dec, 1866. The overs consisted of 6 balls each, and the game was umpired by Messers William Hayman and John Smith. Having won the toss, the Melbourne Cricket Club opted to field first. The spectator count for the day was reported to have been between 10,000 and 15,000 by the Sydney Mail of 26 Jan, 1867, though a conservative estimate of about 8,000 would seem to be more appropriate.

From the statistical point of view, it is on record that the Club had won the encounter by an impressive 9 wickets. For the aboriginals, skipper Wills scored a respectable 25* in the 2nd innings, whilst Johnny Mullagh top scored for his team in both innings with 16 and 33. The Club skipper Richard Wardill had a score of 45 in the 1st innings, the highest in the game. For the indigenous cricketers, all-rounder Cuzens returned very good 1st innings figures of 10-1-24-6. Although defeated, the team members from Edenhope were not disgraced in their first significant game in the big metropolitan city.

There was, however, one instance of unfair behaviour on the part of the Club that led to some pique from Wills, and indeed, the general public. In the words of Gregory Mark de Moore: “The game was won easily by the MCC. But there were whispers throughout the colony that spoke of an ungracious and mean spirited MCC. It became known that Wills had requested the MCC, in deference to the black team’s anxiety in front of such a large crowd, to allow his team to take the field first. The MCC had refused. What seemed to the average man a most reasonable request became a crucible of discontent. The aloof MCC’s refusal to oblige the black team galvanised popular opinion against the MCC and promoted sympathy towards the black team. Wills was defiant after losing to the MCC. He duly informed anyone listening of his disgust with the Club and its treachery. He was not alone in his criticism.” Wills’ pique is understandable, given that he had himself earlier been the captain and the secretary of the Club.

An even more damning accusation had been lodged by the public at large against the Club with respect to this game, that fearing loss of public face in the event of a loss in the game, they had bolstered their numbers by including players who were reportedly not members of the Club, thus contravening their own code of rules in this regard.

The Boxing Day game made the team of Aboriginal cricketers instant celebrities in Australia, and Bell’s Life in Victoria, in their Mar 30 , 1867 issue, reported an overture for the team to travel to Brisbane for a series of games, setting off a trend for local and regional teams to vie with one another for the presence of the native team as well. Whatever the result of the Boxing day game, the popularity and appeal of the Aboriginal team had been firmly established beyond any doubt.

Not everyone, however, was pleased with the sudden rise to fame of the indigenous cricketers. The Australasian of 23 Feb, 1867 reported that, showing utter disdain for the capabilities of the native cricketers, William Caffyn, the Surrey man then coaching the Warwick Club of Sydney, had challenged the entire indigenous team to a single wicket contest against him, an offer that had been viewed with utter revulsion by the media of the time. Making a counter-offer, Tom Wills had backed Mullagh alone against Caffyn for £20, stating that if Caffyn was interested, he would himself be happy to play a single-wicket against the Englishman for £ 50.

At this point of time, Tom Wills was the cynosure of all eyes in view of the wonders he had been able to accomplish with his indigenous cricketers in so short a time frame. The media were generous in their collective praise for his efforts, as is evident from this remark in the Empire of 25 Feb/1867: “Mr Wills has done service to the race by showing, in the instance of these cricketers, how they may be made willing scholars in the acquirement of arts unknown to their fathers. The reputation they have won, under his tuition, will exert a wholesome influence in their favour”.

The proposal

One spectator present at the MCG for the Boxing Day game went by the imposing moniker of “Captain” William Edward Broughton-Gurnett, or WEB Gurnett, ostensibly a man about town and apparently, a man of considerable means. In the immediate aftermath of the Boxing day game, this Gurnett sought out Hayman and Wills and proposed a grand 12-month cricket tour of Sydney and later, England, involving the indigenous cricketers. The plan was suggested essentially as a business endeavour, and Gurnett professed to be willing to finance the venture with respect to the wages, expenses, and clothing for the team members, as well as for the skipper (Wills) and manager (Hayman). Gurnett also hinted at individual bonuses of £ 50 per indigenous player, an unspecified larger sum for the skipper, and a share of the profits for Hayman. The offer seemed too good to be true to Hayman and Wills.

The young and impressionable Hayman, born in 1842, was very enthusiastic and immediately set about trying to add some more native players in view of the projected length of the tour. Untiring in his efforts, Hayman also went around several of the stations requesting the white settlers to release some of their talented native cricketers for the purpose of the tour, and assuring the settlers that “their” men would be well looked after. He applied to the MCC for a return match, and it was duly played over the second weekend of Feb/1867. The Club could only field two of its own members and the balance was made up from a “scratch muster”. Not surprisingly, Wills’ team won this game.

There were some logistical problems surrounding the proposed Sydney tour, however. Barely two days before the departure of the team for Sydney, an urgent and special meeting of the Central Board for the Protection of the Aborigines was convened. It may be mentioned here that Tom Wills was himself a member of this august body. One of the major concerns for the Board was the possibility of the native team being stranded at Sydney if the projected financial outlay for the tour proved to be lacking. After deliberations regarding the propriety and legality of inter-Colony travel by the indigenous players, an appeal was made to the Chief Secretary of Victoria to use his powers to intervene in the matter, and for the government to put a stop to it. Fortunately, the issue died a natural death, being mired under reams of officialdom, and the team departed for Sydney on 14 Feb, 1867, Valentine’s Day.

The team, along with skipper Tom Wills and the managerial personnel, arrived at Sydney by steamer, this being their first stop in their planned tour of the Colonies. Charles Lawrence, by then skipper of the NSW team, and owner of the Pier Hotel at Manly, welcomed the tourists and made arrangements for them to stay at his hotel. Fully aware of the financial possibilities of the tour, Lawrence was eager to form as early an association with the enterprise as possible. One of the early games of the Sydney tour was scheduled to be against Albert Club on the Club premises, and thereby, as they say, hangs an interesting tale.

There was a dramatic moment at the Redfern ground of the Albert Club of Sydney (for whom Charles Lawrence was coach) on 23 Feb, 1867 just as Tom Wills walked out on the field for the 2-day game against the club. Skipper Wills and umpire Hayman were arrested by the local constabulary in connection with a breach of contract complaint. It seems that Wills had made a previous arrangement with businessmen Mr FC Jarrett and Mr W Penman by which he had contracted his touring team of indigenous cricketers to play one game at the Domain of Sydney on 17th, 18th, and 19th Jan/1867. It appears that Wills had not fulfilled his part of this arrangement.

Further enquiry elicited the fact that Wills had also extended his entrepreneurial activities by making similar “arrangements” with some other businessmen as well. It may be worth remembering that, at this stage of his career, Wills had indeed been in dire need of money, and had hoped that offering to play cricket with his Aboriginals on the tour would provide the financial support that he so desperately needed.

As reported in the Empire of 7 Mar, 1867, “The defendant (Wills) it appears agreed with one of the plaintiffs to play a cricket match in the Domain on the 17th, 18th and 19th January with the aboriginal team, but failing in carrying out his contract he was sued by the plaintiffs immediately on his arrival in the colony and arrested under a write of capias by Mr. Penman. On Tuesday we believe a similar writ was served upon him by Mr Jarrett’s attorneys.”

Wills was, however, released shortly after his arrest when ex-Surrey cricketer Charles Lawrence and Mr. O’Brien from Tattersall’s stood as security for him. The legal formalities pertaining to the arrest being settled amicably, the game was then resumed. Historically, these games were initially seen more in the light of the novelty value of a group of Aborigines pitting their cricketing skills against white men. The sporting public, however, soon warmed to the touring group, and began to appreciate the enormity of a small group of ethnic Australians from a small town like Edenhope competing on equal terms with established cricketers from metropolitan cities like Melbourne and Sydney.