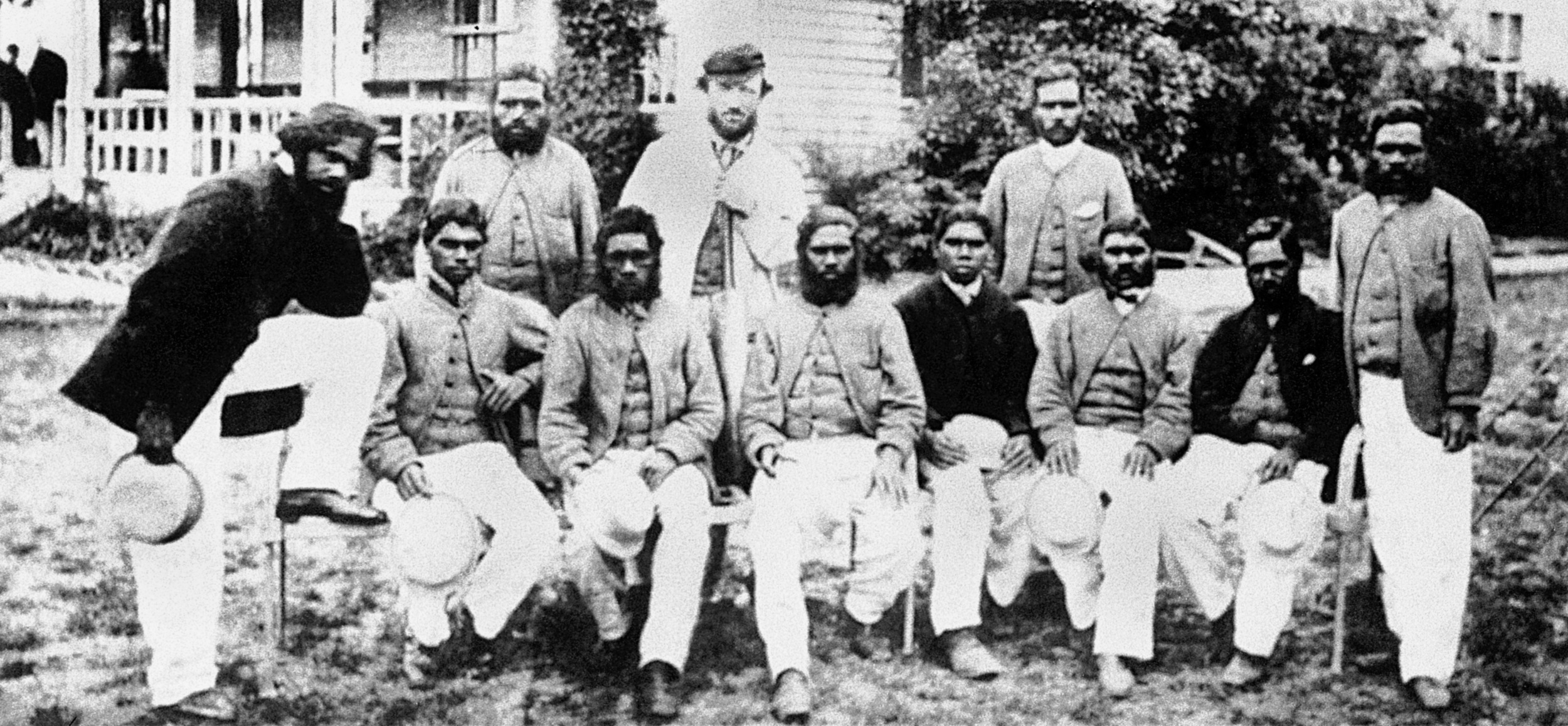

The game against the Melbourne Cricket Club at the MCG in early 1867

(National Library of Australia)

Part 4

The Colonial Tour

The progress of the Colonial tour was not as smooth as had been expected; one major reason for this was the lack of the steady availability of financial support. Several of the cheques issued by William Gurnett began to bounce. Gurnett was arrested in February, 1867 and incarcerated in a Darlinghurst jail, and some of his properties were attached by the legal authorities as cover for his insolvency. As had been anticipated and apprehended by the Central Board for the Protection of the Aborigines, the tourists were left stranded and in a state of complete financial disarray at Sydney by the end of February. A saviour dressed in cricket clothes made his appearance for Manly during the 1-day fixture at Manly Beach on 16 March.

Following a common theme, the story of George Smith begins at Leicester in 1818, when one Charles Smith was apprehended while picking the pocket of a respectable gentleman, thereafter being transported for 14 years. According to the article in The Dictionary of Sydney written by John MacRitchie, Charles arrived at Sydney on the convict vessel Baring 2 in 1819. In the fullness of time, Charles became a successful entrepreneur and business and married Ann nee Wilson. One of their children was George Smith.

By the time Charles passed away in 1845, he had become a man of considerable means, and he left behind a fair amount of landed property, plus several buildings including an hotel in Sydney. Growing up in affluence, George followed his father and became a prosperous businessman himself, later married Ann, nee Baker Smithers, at St. James’ Church, Sydney on Aug 12, 1851, and the couple then raised a large family of 12 children. Shortly after 1860, the Smith family relocated to Manly and George gradually became a prominent citizen and very good friend of Charles Lawrence. Along with his cousin and Elizabeth Street solicitor, George W Graham, George Smith was to become an important financial backer for the pioneering English tour by Lawrence and his Aborigine cricketers that was to follow in the English summer of 1868.

Meanwhile, from the moment that Wills and his proteges arrived at Sydney and put up at the Manly hostelry of Charles Lawrence, the latter became an integral part of the touring team. As the tour went on, Lawrence became more and more of an integral part of the venture. Through the ups and downs of the team’s progress on the Colonial tour, Lawrence was there to provide a stabilising influence. The authority that Wills had been enjoying over the Aboriginal cricketers began to slacken and with time, and a gulf seemed to grow between Wills and the rest of the team. It has been postulated that Wills was by this time a victim of sporadic instances of post-traumatic stress disorder arising from the Cullin-la-Ringo incident of 1861. Another issue, of course, was the increasing problem of Wills’ alcoholism. On the other hand, Lawrence was seen to gradually became increasingly involved with the actual management of the team.

An interesting incident involving the activities of Wills, Lawrence, and their native cricketers during this time is presented in a paper entitled The International Aboriginal Cricketers v Illawarra, presented by AP Fleming. According to The Illawarra Mercury of Apr 9, 1867: “When the steamer from Sydney was signalised (sic) on Thursday afternoon, a great number made their way to the wharf to welcome the Aborigines … The team repaired to the Queen’s Hotel, Queen’s Hall Flats, Market Street, adjacent to the Illawarra Historical Society Museum to refresh and recruit themselves for the next day’s engagement at the willow.”

The 2-day game began at about 11:00 o’çlock on Friday, 5 Apr/1867 in the presence of upwards of about 2,000 spectators packed into the Wollongong Race Course ground. T Galvin, skipper of the Illawarra Club team, won the toss and sent the opposition in to bat. Despite the presence of Tom Wills in the playing XI, Charles Lawrence captained the Aboriginal XI, opening the innings himself along with Bullocky. Although there had been heavy overnight rain necessitating a change of venue for the second day’s play, the visitors held their nerve and ended their innings at 116 all out. The batting heroes for the team were Mullagh (45, the top score from either side) and Wills 21*.

By the time that the visitors had been dismissed, the playing surface had become something of a quagmire, what with the rain and so much walking about on it. The home team could only muster 20 all out, including 3 byes. There were four individual ducks in the innings. Skipper Lawrence and Wills captured five wickets each, and the game was then considered to have been over, the touring team registering a 96-run victory in the single-innings game. The cricket game was followed by some athletic events.

In Chapter 3 of his blog entitled A Flash Outside The Off Stump, blogger Andy Carter provides some information about some of the events of the Colonial tour of 1867. The previous misgivings of the Central Board for the Protection of the Aborigines having been proved to be prophetic, the members of the think-tank of the team were now at their wits’ end about how to raise enough money to take the team back home. William Gurnett, who had promised to finance the tour, had proved to be a charlatan, and there was despondency in the camp.

At this juncture, the enterprise had become bogged down by severe financial constraints. Revising their original plans, the managerial team began to arrange for additional games in order to raise funds to enable them to get back to Melbourne. Lawrence’s local Sydney contacts came in very useful in this regard. As reported by the Sydney Morning Herald of Apr 19, 1867: “Broke, the team is to play a Sydney XI with Wills and Lawrence helping the aborigines. Lawrence was seen as one of the real helpers of the tour and now has usurped Wills in prominence. Doubtless many persons will gladly assist Mr. Lawrence in his praiseworthy efforts. We wish him success, and hope that ample means may be raised to enable the blacks to get back once again to Lake Wallace.”

Is it possible?

Early in 1867, the idea of an England tour with the team had begun to recede from the realm of possibilities. By the end of the Colonial tour, a subtle change was quite evident in the dynamics with respect to the organisation of the team, and the level-headed and resourceful Lawrence gradually assumed the role of the de facto prime mover and main organiser of the team, supplanting Wills in this respect. From contemporary media reports, it appears that the combined financial resources of Hayman and Lawrence were finally responsible for making the trip from Sydney to Edenhope possible at the end of the Colonial tour in May, 1867. The young Hayman was the worst hit financially, reputedly losing about £ 400 personally on the ill-fated Sydney tour. Moreover, none of the native team members could be paid anything for their strenuous efforts.

Heaping more misery on the team of Aboriginal cricketers, four of the native members passed away on the tour, ostensibly from pneumonia, aided and abetted to their liberal intake of alcohol. Tom Wills, however, did not accompany the team back to Edenhope, remaining behind at Melbourne to take up a coaching assignment to supplement his meagre financial resources at the time. Indeed, this was to be the final parting of ways between Wills and his wards, the Aboriginal cricketers, managed on the Colonial tour by Lawrence and Hayman.

Under the gentle influence of Lawrence, there was a steady change in the attitude and demeanour of the native cricketers. While coaching them at their cricket skills was always his primary objective, Lawrence also encouraged them to practice their native skills like boomerang and spear throwing, and to hone their natural athletic abilities. Almost a father figure by now, Lawrence also encouraged them to attend Divine Service. The change was soon apparent among the Aboriginal cricketers. Bell’s Life in Sydney of Nov 30, 1867 had this to say: “In general behaviour and conduct these men do great credit to their mentor. They are very temperate, neat and tasteful in their dress, attend Church with Mr Lawrence regularly on Sundays; and are evidently desirous of improving in moral and social standing … quite aware that they are in good hands ….”

While all this was going on in the camp of the Aboriginal cricketers, however, Charles Lawrence never lost sight of his vision of touring England with his team, an idea that had been constantly in his mind ever since he had toured Australia with the 1861/62 English team under HH Stephenson. In his diary, courtesy Dr Bernard Whimpress, historian and museum curator of the South Australia Cricket Association, Lawrence had written: “… for I thought I should soon make a fortune for I had an idea or a presentiment after I had seen the Blacks throw the Boomerang and Spears that if I could teach them to play cricket and take then to England I should meet with success this impression never left my mind until I had succeeded in forming an aboriginal team and took them to England in 1868….” (The punctuation of the quote, or the lack of it, is unchanged from the original entry in the diary of Charles Lawrence.)

The cast of characters

The team for the projected tour of England began to take a tangible shape shortly. A popular story, reported by Olly Rickets in Wisden, that has passed into English and Australian folklore, concerns one of the chosen group of cricketers, the strong and muscular 5’8 ½” tall Dick-a-Dick, one of three brothers, the others being Jellico and Tarpot.

Three young children of white settlers, Isaac Cooper (9 years), Jane Cooper (7 years), and Frank Duff (3 years), were reported missing in the Wimmera region of Western Victoria on Friday, 12 Aug/1864. Search parties began to scour the surrounding countryside, but torrential rain prevented any meaningful tracking of the missing children. In desperation, the father of Frank Duff requisitioned the help of three expert Aboriginal trackers, one of whom was called Dick-a-Dick (or King Richard), the others being Jerry and Fred, to go by their Anglicised names. (Some of the dates quoted in the original article are not found to be consistent with the standard British calendar for 1864, and have been amended accordingly).

The trackers began their seemingly futile quest on a Saturday, Aug 20, 1864, over a week after the children had been reported missing. Reading vital clues in almost imperceptible signs along the way, they were able to locate the children later in the day. The clearly exhausted, frightened and shivering children were restored to the bosom of the anxious families amidst general relief and jubilation. It is said that the incident had been reported in the contemporary press and that a collection of £ 15 had been undertaken, out of which £ 5 had been handed over to the trackers, the rest being kept with their white employer.

Johnny Mullagh in his later years

Another remarkable member of the team hailed from the station of Mullagh, near Harrow, Victoria, where he is believed to have been born in 1841. A member of the Madimadi tribe, he was known by the Anglicised name of Mullagh Johnny in his youth, though his native name was Muarrinim or, variously, Unaarrimin, and spent a considerable part of his life on the Mullagh property of JB Fitzgerald, later moving on to the Pine Hill station of David Edgar. In his biography of Johnny Mullagh for the Australian Dictionary of Biography, DJ Mulvaney drops a veiled hint that there may have been a drop of European blood in Mullagh’s ancestry.

DJ Mulvaney says: “About 1864 Mullagh and other Aboriginal station hands learned the rudiments of cricket from Edgar's schoolboy son and two young squatters, T. G. Hamilton and W. R. Hayman.” One can therefore infer that Mullagh was at the Pine Hill station at this time. Over a period of time, the 5’10” tall Johnny Mullagh was to become an outstanding all-rounder, coupling his robust batting skills with his round-arm variety of bowling with a “free wristy style.” We will return to this stalwart later in the narrative.

Johnny Cuzens

One of the other highly regarded native cricketers was Johnny Cuzens, reportedly named after a Balmoral shopkeeper, who was generally an all-rounder, but after his sterling performance with the ball in the famous Boxing Day game (in which he had captured 6 wickets), Cuzens soon came to be regarded as a “capital bowler.” Together with Johnny Mulllagh, Cuzens was to play a pivotal role for the native Australian team on the 1868 England tour.

Harry Bullocky

Harry Bullocky, ‘a burly and large man” from the Balmoral station, turned out to be a fairly proficient wicketkeeper-batsman for the team, a right-hand opening batsman, and spoken of being “at once the black bannerman and Blackham” of the team. In his book The Black Lords of Summer, Ashley Mallet says: “Bullocky was a courageous wicket-keeper with a granite frame…. It was Bullocky’s work up to the stumps, always the hallmark of a top-class glove-man, which endeared him to the enthusiasts…” His virtuosity close to the stumps was to allow him to effect 28 stumpings off the bowling of Lawrence alone in his 39 matches on the England tour. The name Bullocky may have had some connection from his work as the driver of a bullock team. His initiation in cricketing skills seems to have come from Tom Hamilton at the Bringalbert station, and later from Charles Officer at the Mount Talbot station.

The following chart shows the native names and the given Anglicised names of the members of the final list of 13 Aboriginal cricketers selected for the projected tour of England in the English summer of 1868. The comforting thought of having the solid presence of Alderman George Smith and his solicitor cousin George W Graham as financial backers for the tour acted as the final incentive for Charles Lawrence and young William Hayman as they went about their preparations. At this point, it may be prudent to point out that of the 13 native cricketers chosen, perhaps 8 or 9 could be thought of as being specially endowed with cricketing skills thanks to the intensive coaching by Wills and Lawrence. The rest, being naturally gifted athletes, were to shine on the tour with mainly their considerable non-cricketing skills.

The members of the Aboriginal team had sported a largely white uniform with a red trim and belts, completed with blue neck-ties during their Melbourne games of 1867. Lawrence now felt that something more distinctive was in order for the pioneering English tour. The new scheme saw the native cricketers kitted out in white trousers and bright red “Garibaldi” shirts, and each player had a wide blue sash diagonally across his chest. The ensemble was topped off with different coloured caps, the individual cap colours to be mentioned in the scoresheets for easy identification of the players.

As fine as the scheme was from a theoretical point of view, practical difficulties soon surfaced when it became apparent that the differently coloured caps were too small to identify the distinctive colour from a distance. Eventually, the players used sashes of colours matching their caps in England. The Mercury of Friday, Nov 1, 1867, reporting from the Wollongong Race Course Ground, was to make the following comment on the individual colour scheme in the attire of the Aboriginal team: “Mullagh, scarlet; H. Rose, Victoria plaid; Cuzens, purple; Dick-a-Dick, yellow; Sundown, check; Redcap, black; Mosquito, dark blue; Peter, green; Jim Crow (Neddy), pink; Bullocky, chocolate; King Cole, magenta; Twopenny, McGregor plaid; and Mr. C. Lawrence, all white. Their costume for sports is white tights and different coloured trunks and caps.” Harry Rose, however, did not make the trip to England eventually, being replaced by Charley Dumas.

The Epic Journey

It was finally on Sep 16, 1867 that a large charabanc powered by four horses rolled out of Edenhope on the first leg of the epic journey to England. Crammed with Lawrence, Hayman, a coachman, 12 Aboriginal cricketers, a cook, and the assorted luggage and kit of the members of the party, the charabanc made slow progress on the uncertain muddy tracks available at the time.

An eventful eight days on the road that included thunderstorms and ambush by highwaymen brought the party to Warrnambool, along the legendary Shipwreck Coast, where they played the local XVI. The schedule, as originally planned, had been to proceed to Geelong, going on to Ballarat, Castlemaine, Bendigo, and then on to Melbourne, before reaching Sydney. An incident of 15 August, however, caused an unfortunate disruption of the carefully laid out tour itinerary.

It seems that there had been an incident of some of the selected Aboriginal cricketers being under the influence of liquor and causing a public disturbance, as a result of which three of them had been placed in a lock-up in Portland, the oldest European settlement in Victoria, by Mounted Constable Thomas Kennedy. Kennedy had then brought the incident to the notice of his superior and had also informed the Central Board for the Protection of the Aborigines, requesting the Board to intervene in the movement of the native cricketers out of the state, and onwards to England, stressing the deleterious effect that alcohol was likely to have on the natives of the party.

The issue was then compounded by Dr WT Molloy of Balmoral, a medical man and humanitarian, by voicing his concerns in the public domain, particularly in the media of the times, about the advisability of taking the group of Aboriginals out of their accustomed environment to a climate and ambiance they were not familiar with. The main thrust of Dr Molloy’s misgivings was that exposure to the unfamiliar English climate and the free availability of alcoholic beverages in England were likely to prove fatal for the native cricketers. The good doctor brought these worries to the attention of Brough Smyth, the then Secretary of the Central Board, early in October, requesting him to use his influence to prevent the touring party from leaving Australian shores. As before, the Board found themselves unable to come to a firm decision about the issue at their 11 October meeting, and the grand debate about the advisability of the England tour by the Aboriginal cricketers continued unabated.

In an attempt to circumvent any possible objections that the Central Board for the Protection of the Aborigines were likely to raise about such a drastic step, a well-planned subterfuge was played out that enabled the touring party to finally embark on their journey to England. It had been announced that the team would play a game at Bendigo on 2 Nov/1867, later going on to Ballarat and Castlemaine. The word was further spread about that the team would then take a fishing holiday at Queenscliff, a small town in the Bellarine Peninsula of southern Victoria, close to Port Phillip.

The New Zealand Maritime Record, a website maintained by the NZ National Maritime Museum, states that not much is known about the first version of the 6 models of the Rangatira which, serviced by a British crew, used to be in passenger service between London and Australian ports as early as 1857. The next version was a steamer built of iron in Scotland in 1863 and was to play a significant role in the next part of this fascinating story.

There was, of course, no fishing holiday, and the party was at this time minus Hayman, who had to remain a few days in Melbourne to await the arrival of some replacement Aboriginal cricketers. Hayman was to then make his way to Sydney separately on October 29. Under cover of the misleading publicity about the “fishing holiday”, the remainder of the group, under the stewardship of Lawrence, proceeded to board the Rangatira off the Port Phillip Heads. An unscheduled departure of the Rangatira conveyed the cricketers to Sydney. While the members of the Central Board for the Protection of the Aborigines were not particularly amused at the turn of events, the bold move on the part of Lawrence was seen with an indulgent eye by the media. “The black cricketers have been too many for the Board” reported Argus. According to the Age, the Board had been “check-mated by the speculators.”

It seems from contemporary reports that Lawrence and his men had reached Sydney on Monday, 4 Nov/1867. The Wollongong game was played over Tuesday and Wednesday, the 6th and 7th Nov/1867, play beginning at 11 o’çlock each day. Having won the toss, Lawrence sent the local team into bat first. In their two innings, the local Club mustered 27 all out and 102 all out, while the visitors scored 86, and required a further 44 runs in the 2nd innings to win the game. They did so by scoring 45 for the loss of 2 wickets.

The write-up in The Mercury of Nov 1, 1867 also contains the following enigmatic information: “After several matches in this colony, the team will proceed to China about December with the intention of playing a few matches in Hongkong, after which they will leave for England where they hope to arrive in May next. Their arrival is already anxiously looked forward to for John Bull is ever on the lookout for novelties and new sensations. It is not likely that the Aborigines will be able to compete successfully with the best class of English players but the boomerang, which is known in England only as a toy and not as a weapon of warfare, spear throwing and other athletic exercises, will certainly create a great excitement.” One is left scratching one’s head over the “China” angle.

The above game was followed by some others, with mixed results for the touring party. The last game before their departure for England was against the Army and Navy at the ground of the Albert Club, and was played over 4th and 5th Feb/1868, with HRH the Duke of Edinburgh, then on an Antipodean visit, attending on both days. One interesting member of the Army and Navy team was the Surrey professional William Caffyn, spending some time coaching in Australia after the English tour of 1863/64 under George Parr. After the game ended in a draw, there was the customary exhibition of athletic skills by the Aboriginal members of the team, to the gratification of the 9,000 strong crowd enjoying pleasant weather.