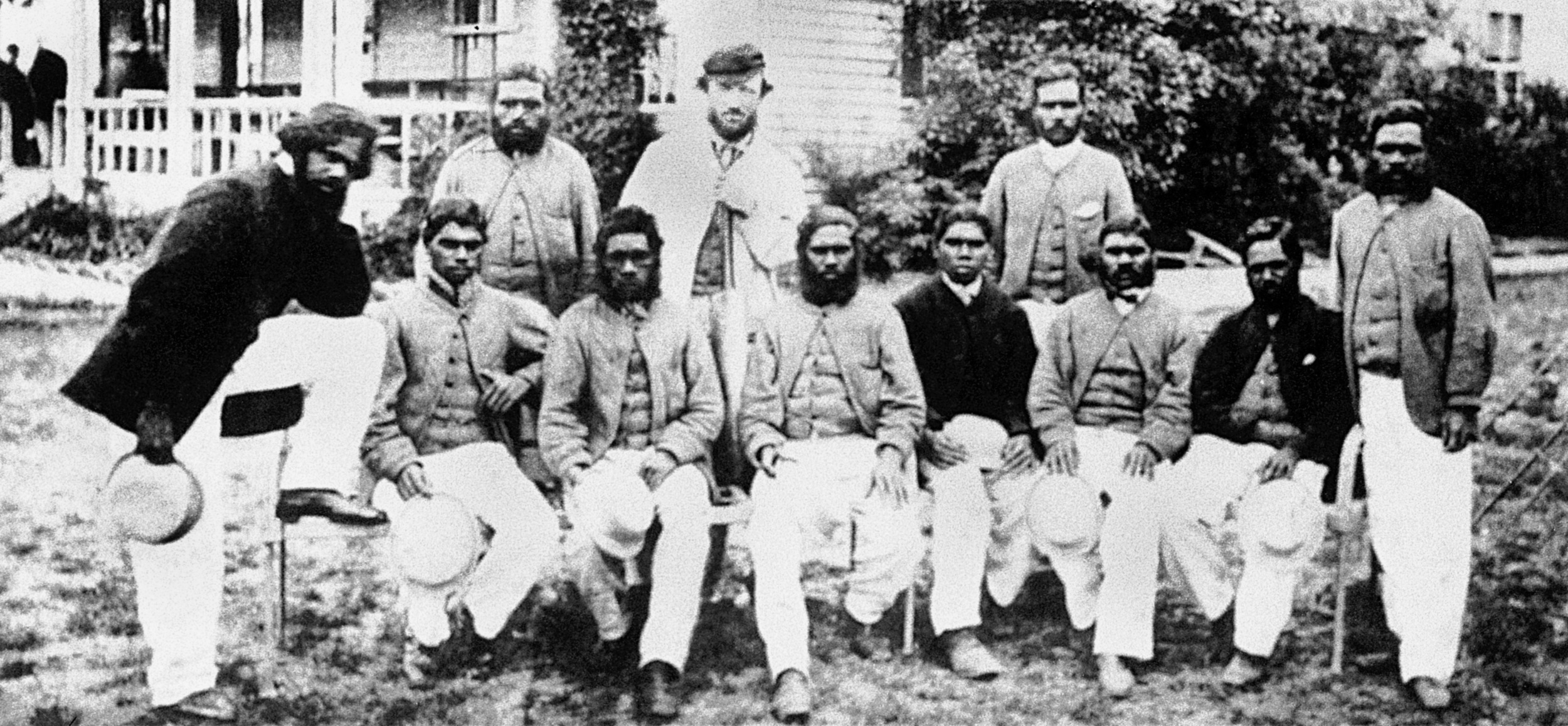

Lawrence and his Aboriginal team of 1868 resplendent in their colourful attire in England

The Voyage

The Lloyd’s Register for the period 1868-69, lists a Scottish sailing vessel named the Parramatta, built at Sunderland in the James Laing Dockyard in the year 1866, for the passenger trade of Devitt & Moore between London and Sydney. Made of teak wood and English oak with iron beams, the sturdy three-masted sailing vessel had a tonnage of 1521 and was of the Blackwall frigate class. The ship was formally launched in May/1866. Named after the Parramatta river near Sydney, it was used as a wool clipper and passenger vessel. Between her launching and 1874, the vessel was under the command of Captain John Williams. During this period, the voyage between London and Sydney would take an average of about three months, as would the return voyage.

Painting of the Parramatta off the Sydney Heads by artist Frederick Tudgay.

The beginning of the long-cherished dream of Charles Lawrence of touring England with a team of Aboriginal cricketers became a reality on the Saturday, Feb 8, 1868, when the Parramatta weighed anchor at Sydney harbour, carrying a substantial cargo of wool in the hold. For the native cricketers not accustomed to long sea voyages, the prospect of a three-month voyage was an unnerving one, particularly given that William Hayman, with whom they had developed an easy relationship over the last two years, and whom they had come to regard as a trusted friend by now, would not be travelling with them.

It had been planned that Hayman would go on ahead of the rest of the team on a previous ship to make appropriate arrangements for match fixtures, travel schedules, and accommodation for the team members in England upon their arrival in the Home Country. Accompanying the Aboriginals on the Parramatta were the managerial group for the tour comprising skipper Charles Lawrence and the financial backers George Smith and George Graham. A methodical man, Graham was in the habit of maintaining an accounts ledger during the tour. This valuable document had later come into the possession of the legendary Australian leg-spin and googly bowler “Tiger” Bill O’Reilly, and has since then provided much valuable information to cricket historians about the events of the historic tour.

Fortunately, the Parramatta had some spacious cabins, and all the Aboriginal cricketers were billeted in the same large room so as not to feel isolated among the other passengers on board. Sensing the disquiet among his wards about the long voyage, skipper Lawrence wisely enlisted the aid of the master of the vessel, Captain John Williams, an experienced and sagacious man whose very appearance seemed to have a palliative effect on the native cricketers. The Captain’s simple homily before these uncomplicated men from the Australian outback about the benefits of simple living and about the perils of excessive indulgence in alcohol became a recurrent theme on the voyage.

In addition, captain John Williams would often speak to the natives about Christian beliefs and try to instil in them some of the basic tenets of the Christian faith. The Aboriginal cricketers found his presence very inspiring and comforting and by the time they landed at Gravesend on May 13, 1868, came to regard Captain John Williams as something of a father figure. William Hayman was there at the quayside to greet his team upon their arrival at Gravesend.

There may have been an element of serendipity in the date of arrival of the Aboriginal cricketers in England. When they first set their feet on English soil at Gravesend on 13 May/1868, it was almost exactly 81 years since the First Fleet had set off from the same place bound for Australia with the first consignment of British convicts and other settlers, the historical date then being 13 May/1787, when the fleet of 11 ships, under the command of Arthur Phillip, had moved out towards the Antipodes.

The British press was all agog with the arrival of the dark cricketers from the Australian Colonies. The Maidstone Telegraph of Saturday, the 23rd of May, 1868 reported: “They are the first Australian natives who have visited this country on such a novel expedition, but it must not be inferred that they are savages; on the contrary, the managers of the speculation make no pretence to anything other than purity of race and origin. They are perfectly civilized, having been brought (up) in the bush to agricultural pursuits as assistants to Europeans, and the only language of which they have a perfect knowledge is English.”

The publication of Charles Darwin’s The Origin of Species in 1859 may have already whetted the curiosity of the average Englishman about these men from the Australian bushlands.

The start of the tour

Lawrence was now in the land of his birth along with his exotic cricketers. It was a relatively mild summer in England in 1868, and there was an estimated gathering of about 7,000 spectators populating the stands at the newly opened, and later to become iconic, Kennington Oval as the Surrey Club opening batsmen set the first ever Australian cricket (or, for that matter, any Australian sporting) tour of England in motion, at about 11 o’çlock of May 25, 1868. The home team finished with 222 all out, scored in 115 (4-ball) overs. One TW Baggallay top scored with 68 runs. Interestingly, this same gentleman was to change his name in July of the same year, assuming his new moniker of Thomas Weeding Weeding. For the visitors, skipper Lawrence captured 7 wickets, with Mullagh chipping in with 3 of his own.

The Australian touring team was dismissed for 83 in their 1st innings, Mullagh contributing 33 to the paltry total. Invited to follow on, the tourists put up a better performance in the 2nd innings, with a total of 132 all out, of which Mullagh contributed 73, the only fifty of the innings, and skipper Lawrence contributed 22.

In his article entitled All Right There – The 1868 Aboriginal Tour Of England, writer Dave Wilson says: “his (Mullagh’s) high score leading to the crowd rushing onto the field and carrying him jubilantly to the pavilion.” The home team thus won the 2-day game by an innings and 7 runs. A display of the athletic skills of the native Australians followed the cricket.

The spectator turnout over the 2 days was estimated at about 20,000, with £ 603 2 shillings and sixpence being taken at the turnstiles. Of this amount, the tourists received £ 309 9 shilling and 1 penny after all expenses, an unexpectedly handsome amount after only their first game. Mullagh’s all-round performance was particularly satisfactory for the visitors. The fact that the scorecard for the Surrey Club innings shows Bullocky, the designated wicketkeeper of the visiting team, who, besides his two stumpings in the innings, to have also bowled 5 overs in the innings, infers that it had been Mullagh, the “occasional wicketkeeper” behind the stumps for a part of the innings.

The Sheffield Daily Telegraph was generous in appreciation of the efforts of the tourists, as follows: “This most interesting match, decidedly the event of the century, commenced to-day at the Oval, and the weather having cleared up there was every prospect of a large gathering to witness ‘the blacks’ perform. Contrary to general expectation, the aboriginal team turned out to be really a fine body of men, of superior type for Australians, and in build and physique not only far removed from the low, negro type of the genus homo, but able ‘to take their own part’ with well-developed Europeans.”

Quoting the seminal research done by Mulvaney and Harcourt, blogger Andy Carter observes that: “Geographically the tour was broadly split into three parts. From their arrival in May until the 23rd June the team played 10 matches in London and the South-East. From June 26th until September 15th they toured the north of England, playing 25 further matches, mostly in the industrial towns and cities of Yorkshire and Lancashire, although they did also make visits to Swansea and Norwich on this leg of tour. The last part of the tour involved 12 more matches in London and the Home Counties between mid-September and mid-October. The poor weather and shorter daylight hours for this last section of the tour meant much smaller crowds, with some games proving to be loss making ventures.”

A single day game played at Mote Park, Maidstone, on May 29, though drawn, was to have a significant impact of the later part of the tour and proved to be a very effective exercise in public relations. The local team fielded several aristocratic members against the Australian visitors, and there was an assemblage of about 80 of the local gentry including many prominent “blue-blooded” citizens at the luncheon arranged between innings. One such notable and illustrious personage at the lunch table that afternoon had been the Marquis of Anglesey, an important and influential member of the MCC at Lord’s.

It seems that the MCC had rejected an earlier request for a game against the MCC at Lord’s. It is very possible that a later quiet recommendation from the Marquis of Anglesey to the MCC board may have been instrumental in the MCC members reversing their earlier decision and allotting a game at Lord’s against the Club. The MCC team for this particular game was to include “an Earl, a Viscount, and a Lieutenant-General”.

June 12 turned out to be an important date in the documented annals of cricket, being the first day of the 2-day game between the MCC and the Australian Aboriginal team. It was the very first time in the colourful history of cricket that an Australian cricket team had tread on the hallowed turf of the most legendary of all English cricket grounds. The English cricket Establishment had, in a symbolic sense, placed a seal of approval on the first ever Australian cricketers in the Home Country, and the names of the relatively unknown native cricketers from the remote Australian bush would now be indelibly woven into the fabric of cricket history. In a cricketing sense, a mention in the 1869 edition of Wisden of a fixture described as “MCC versus ‘The Australians” played at Lord’s went a long way to establish the social and sporting credentials of the first Australian team to tour England.

The Lord’s game turned out to be quite exciting. Batting first, the MCC put up a decent total of 164 all out from 88 overs. The only individual fifty of the innings came from the bat of the Harrow School and Trinity College, Cambridge, alumnus, solicitor, and the then Secretary of the MCC, Robert Fitzgerald, who scored a round 50. For the tourists, all-rounders Mullagh (5/82) and Cuzens (4/52) were the successful bowlers, one MCC player being run out.

The visiting team replied with a robust 185 all out, with Mullagh contributing 75, and “receiving loud and well-deserved cheers as he returned to the pavilion,” and skipper Lawrence scoring 31. For the MCC, another Harrovian, CF Buller, captured 6 wickets for an unknown number of runs. Facing a 1st innings deficit of 21 runs, the MCC managed to plod on to a 2nd innings total of 121 all out. This time, Cuzens (6/65 with 3 wides) managed to outdo Mullagh (3/19) with the ball. The Australian Aboriginal team therefore required 101 runs in the 2nd innings to win the exciting game. It was not to be, however. Skipper Lawrence, nursing an injury, was forced to seek the help of a runner, who subsequently ran him out to leave the team precariously placed at 5 wickets down for only 13 runs. The Australian team was dismissed for a mere 45 in the last innings of the game to concede victory to the MCC by 55 runs. Cuzens (21) and Mullagh (12) were the only two men in double figures.

King Cole

Death of King Cole

It was shortly after this game that the tourists were to suffer a bereavement.

Barely a week after the Lord’s game, the slightly built all-rounder King Cole of the visiting team, sometimes referred to as Charlie Rose, and hailing from the Wimmera region of Victoria, “arguably the side’s most proficient fielder,” fell ill with a chest ailment. It was soon apparent that the illness was more serious than had been thought.

Dave Wilson quotes a London Standard article of 26 Jun/1868, as follows:

“DEATH OF ONE OF THE ABORIGINAL BLACK ELEVEN:

We regret to say that King Cole died last night at Guy’s Hospital, from an attack of inflammation of the lungs. He was removed to Guy’s on the return of the eleven from Hastings, where they had been playing up to Wednesday evening. King Cole was under 30 years of age.”

Mulvaney and Harcourt confirm that the euphemism used in the above news item regarding the cause of death should be interpreted as King Cole succumbing to tuberculosis, the “white scourge”, aggravated by pneumonia. The historical fact remains that King Cole passed away at Guy’s Hospital, London, on Wednesday, June 24, 1868, having played in only 7 games on the tour, his last appearance on an English cricket ground being in the game against East Hants Club at the Club ground at Southsea, on the 15th and 16th June of the previous week.

A grieving Charles Lawrence was at his bedside when King Cole breathed his last in the London hospital.

The passing away of one of their fellow players resulted in a short period of depression among the other Aboriginal members of the team. Martin Flanagan explains that there was a belief among the Aboriginal population that: “The ultimate terror for a traditional Aboriginal person is to die outside their ‘country’, away from the company of their ancestral spirits, thereby condemning their spirit to forever wander alone.” It may be recalled at this point that one of the prime concerns of the Central Board for the Protection of the Aborigines had been the uncertainty over whether or not the Aboriginal cricketers, being accustomed to the relatively warmer and drier climate of their native land, would be able to adjust to the colder and relatively more moist climate of England.

The plaque reproduced here was erected on June 26, 1988, in the memory of the departed pioneering cricketer King Cole, and was donated to the Aboriginal Cricket Association by Hillier Nurseries Ltd. It can be seen embedded in the grass at the base of a fenced in tree at Meath Gardens, formerly known as the Victoria Park Cemetery, where the former cricketer had been finally laid to rest.

The inscription reads:

“In memory of King Cole, aboriginal cricketer who died on the 24th June 1868.

Your Aboriginal dreamtime home. Wish you peace.

Nyuntu anangu tjukurpa wiltja nga palya nga.