Postage stamp commemorating 150 years of the first ever international cricket tour by an Australian team in 1868. The stamp was released on May 1, 2018.

On return

The tour officially over, it was now time to return home. Four of the players, Bullocky, Peter, Tiger, and Twopenny, and financial backer George Smith found themselves on board the Dunbar Castle on Oct 19, 1868 on the way back home to Australia.

Smith was taking home some prime stallion bloodstock. Graham remained behind in England. Interestingly, there appears to be a reference to a daughter of Charles Lawrence accompanying her father and the rest of the 1868 tourists on the Dunbar Castle on the way back to Australia.

The rest of the party joined the same vessel at Plymouth about a week later after a short holiday at Devon. The vessel docked at Sydney on Feb 4, 1869, and the touring party was finally home having been away for four days short of one year. Actually speaking, remembering that the touring party had originally set out in a charabanc from Edenhope on Sep 16, 1867, the Aboriginal cricketers had been away from home for about a year and five months.

It may be remembered that one of the principal objectives of Charles Lawrence in organising such an elaborate tour had been to make a profit out of the enterprise. Going by contemporary reports and the invaluable accounts register of George Graham, the early part of the tour had been quite lucrative for the organisers. Relatively mild weather and the curiosity factor regarding the Aboriginal cricketers had largely been responsible for a profitable first 12 weeks or so of the tour. During the second half of the tour, which included the months of September and October when the weather had not been very kind to the cricketers, the profits had fallen away drastically.

Despite several mutually conflicting reports on the issue, and after a close study of Graham’s ledger, the conclusion is that, after all expenses had been taken into account, the tour had made a profit of about £1100. The total takings from the games had been estimated to be about £5416, while the costs were thought to have been about £3224, exclusive of Graham’s subsidy in Australia. The question of whether the players had been actually paid anything over and above their stay and allowances is shrouded in mystery. It is, however, true that players like Mullagh, Dick-a-Dick, Cuzens, and a few others had received prize money on several occasions, specially from the native sports they had engaged in, and it is very likely that these amounts would have been shared around among themselves.

In retrospect, the 1868 venture appears to have been the single most important Australian tour of England. In the words of former Australian captain, Ian Chappell: “I think we should cast our mind back to the 1868 side – the first Australian side that toured England – the Aboriginal side … if they hadn't of been so successful and if they hadn't endured those hardships, it may not have been easy, so easy for those that have followed.”

In recognition of the historic significance of the 1868 England tour, and even though no first-class matches were played by the team in England, all the 14 members, including skipper Charles Lawrence, were officially inducted into the Sport Australia Hall of Fame in the year 2002 as a result of an initiative taken by Ian Chappell, and were awarded player numbers AUS 1 through to AUS 14, generally in alphabetical order of their native names. Skipper Lawrence was awarded AUS 7. Johnny Mullagh and Johnny Cuzens were awarded numbers AUS 13 and AUS 14 respectively, while Dick-a-Dick was documented with the number AUS 10.

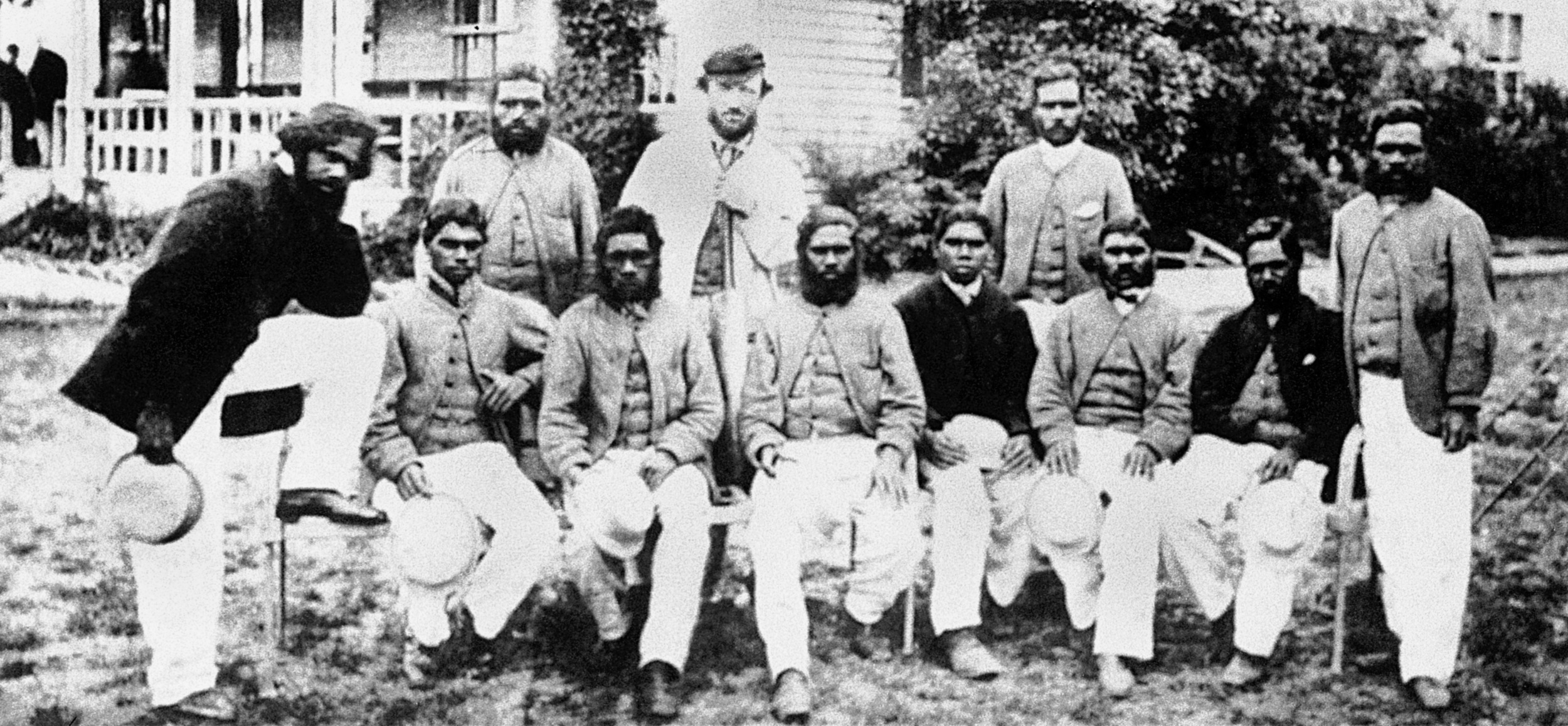

The commemorative postage stamp at the top of this article was issued by Australia Post, and shows 10 of the original 13 Aboriginal players in their “Garibaldi” uniforms, together with skipper Charles Lawrence. The native players missing from the group are King Cole, who had died on the tour, and the duo of Sundown and Jim Crow, who had both been sent back midway through the tour. Also appearing in the picture sitting on the ground is William Shepherd, who sometimes deputised for Lawrence in a few of the games and occasionally functioned as an umpire.

New Legislation

A Gazette Notification appeared in the Colony of Victoria on Nov 11, 1869 beginning with the words: “BE it enacted by the Queen’s Most Excellent Majesty by and with the advice and consent of the Legislative Council and Legislative Assembly of Victoria in this present Parliament assembled and by the authority of the same as follows….” The subtitle clarified the purpose of the legislation, which was: “To provide for the Protection and Management of the Aboriginal Natives of Victoria.” Comprising several statutes relating to the management and welfare of the native population, the legislation comprised several sections.

This Memorial to the Aboriginal cricketers of the 1868 England tour was unveiled by former Australian captain Vic Richardson at Edenhope on Saturday, Oct 13, 1951. The plaques shown on the surfaces were applied subsequently and unveiled later in 2002.

A part of Section Number 6 made it a punishable offence for any Victorian Aboriginal to be moved out of Victoria without express permission from the administrative authorities, as follows: “If any person shall without the authority of a local guardian…. remove or attempt to remove or instigate any other person to remove any aboriginal from Victoria without the written consent in that behalf of the Minister every such person shall on conviction be liable to a penalty not exceeding Twenty pounds or in default to be imprisoned for any term not less than one month nor more than three months.” This legislation proved to be a dampener for the more proficient Aboriginal cricketers with respect to participating in any away game outside the confines of Victoria in future

The star player

The player profile for Johnny Mullagh gives his date of birth as being Aug 13, 1841, near Harrow, Victoria. A genuine all-rounder, he excelled at the wicket as a right-hand batsman, a right-arm round-arm bowler, and as a more than average wicketkeeper. Of his 47 second-class games, 45 of them were played on the 1868 English tour. His only documented first-class match was for Victoria against Lord Harris’ XI at the MCG from Mar 7, 1879. He scored 4 and 36, top scoring for Victoria in the 2nd innings, and held a catch in the visitors’1st innings. He also bowled 3 wicketless overs in the 1st innings. The Sporting Life of Oct 28, 1868 had commented: “Mullagh received an offer from the Surrey club of an engagement at the Oval.” However, the veracity of the statement had never been investigated in depth.

Mullagh’s last documented game was a drawn single-day affair for Melbourne against the Bohemians at the MCG on Nov 5, 1879. Opening the batting for his team, Mullagh was run out for 10. It is said that he continued to play for the Harrow Club, a member of the Murray Cup Competition, till 1890. A bachelor, he is reported to have passed away on Aug 14, 1891, aged 50 years, at his camp at the Pine Hills station.

He lies in peaceful repose in the Harrow cemetery, and the Hamilton Spectator had thought it fit to sponsor a subscription towards the construction of an obelisk in his honour that was later established at the “Mullagh Oval” in Harrow. To this day, an annual cricket competition, known as the Johnny Mullagh Cup, is contested at Harrow between 11 descendants of the original 1868 Aboriginal XI and players from the Western Districts of Victoria.

The commemorative obelisk at the Johnny Mullagh Memorial Park, Harrow

As reported by the Singleton Argus (NSW) in April 1913, the Rev J Kirkland, who had performed the last rites of Mullagh in Aug, 1891, had made the following comments about the great cricketing pioneer: “I gave an address over his grave. I remember stating he had three characteristics that would adorn any white man and few could lay claim to them. They were, he never was known to be drunk, he never used an oath, he never disputed an umpire’s decision”. During the funeral service, the Reverend had also read out form a poem he had himself written about Mullagh. The last line of the poem had read: “The whitest man and the smartest one that ever played old England’s game”. There could not have been a better epitaph for the great cricketer.

Cuzens and Mosquito

According to Jenny MacLaren in her article entitled The South-West’s Links to a 150-Year-Old Sporting Legend Are Being Kept Alive, the brothers Yellenach (better known as Johnny Cuzens) and Grongarrong (better known as Jimmy Mosquito), are both now believed to be lying at eternal rest at Framlingham, in the Western District of Victoria “in undisclosed graves.” Legend has it that quick round-arm bowler Johnny Cuzens used to be “the Jeff Thomson of his day”, and was also known to have “a stare-down like no other.” He was also one of the quickest sprinters of the team. His brother Mosquito was renowned for his proficiency with the stock-whip during the exhibitions of native skills. In the end, Cuzens is believed to have succumbed to dysentery.

Dick-a-Dick

Olly Rickets, writing in Wisden, begins his article entitled Dick-a-Dick and the Aboriginal Tour of England with the lines: “On June 13, 1868, Dick-a-Dick was carried from the Lord’s pitch into the dressing rooms on the shoulders of a throng of spectators who had adopted him as their new hero. He had scored a grand total of eight runs – which was admittedly better than his tour average of 5.26 – and had not taken a single wicket or catch. Not many cricketers have managed to provoke such a reaction from the usually placid Lord’s crowd, let alone one who evidently wasn’t actually very good at cricket. But then not many people have lived a life so full of incident for such an event to seem like just another day.”

Born at some time between 1845 and 1850, Dick-a-Dick was a natural athlete and expert tracker. Very temperate in his habits with regard to alcohol, he had been known to lay his leangle on the backs of some of his fellow native cricketers in England if he felt that they were being drunk and unruly. It is reported that the famous leangle of Dick-a-Dick has been under the custody of the Lord’s Museum since 1946. He was probably the only affluent member of the group, earning his money from his astonishing feat of dodging cricket balls thrown at him from close up, sometimes with as many as 7 people propelling the ball towards him simultaneously.

The infatuation between Dick-a-Dick and a white lady during the England tour has already been touched upon. Being himself abstemious by nature, and an admirer of the Mounted Constable Kennedy, who had reported the alcoholic disturbances caused by some members of the chosen touring team at Portland prior to the England tour, Dick-a-Dick is reported to have adopted Kennedy as his family name in later life, and had named his grandson Jack Kennedy. In later years, his great-grandson William John Kennedy, a prominent activist for the cause of the Aboriginal people, and a highly respected member of the indigenous community, was to be elected “Male Elder of the Year” in 2003.

Upon his return from the tour, Dick-a-Dick and his wife Amelia moved to the Ebenezer Mission, established near Lake Hindmarsh, Victoria, in 1859 by the Moravian Church. He was in very indifferent health around this time, and under the influence of the German missionary, the Rev FW Spieseke, embraced Christianity and was baptised on July 30, 1870. One version of his life story has him passing away on 3 Sep/1870. There is an apocryphal story, often attributed to his daughter, of his clutching onto a faded and crumpled photograph of a white lady even as he was being lowered into his casket. Mulvaney and Harcourt, however, are of the opinion that Dick-a-Dick had died sometime in the 1890s.