The 70-year-old Lawrence in his batting stance

Part 8

The last days of Tom Wills

Let us now go back to the story of the renowned Australian cricketer of the 1850s and 1860s, Thomas Wentworth Wills.

As noted earlier, he had gradually become a slave to alcohol following the gruesome murder of his father in their Queensland estate in 1861. Dipsomania soon followed, and he became heavy of frame with a decided paunch marring the lines of the once handsome athletic figure, his face began to sport a permanent flush, and his jowls became heavy from his dissolute lifestyle. He fell into the habit of running up debts and being deceitful about his financial status and transactions. His personal habits became careless, and he was no longer the dandy that he was before. Towards the end, Wills presented a sorry image of drunkenness and destitution.

Miraculously, he was never convicted of any violent behaviour or misdemeanour while under the influence of liquor, although his drinking habit was to be the ultimate cause of his declining sporting career. The Minute Book of the Melbourne Cricket Club had an entry dated Mar 22, 1870 stating that a letter had been received by the Club from Mr TW Wills claiming that he had been threatened with arrest and legal proceedings on a recent trip to Tasmania because he had defaulted on a bill of 9 shillings and 6 pence raised four years previously. When questioned, Wills had vociferously claimed that the accusation was false and that he had paid the bill in question. Sadly, incidents of a similar nature would become increasingly frequent in the later phase of Wills’ life.

In the early 1870s, Wills was overlooked for the professional’s appointment with the MCC in Melbourne and missed the games against the visiting English team of 1873/74. He was also not hired as a coach by the MCC. When Wills wrote a letter to the MCC on 8 Dec/1874 requesting a position as umpire, the Club referred the matter to the Intercolonial Match Committee, who, after due consideration, vetoed the appointment. The self-esteem of Wills, desperately in need of steady financial support, was at rock bottom during this phase of his life.

Surprisingly, Wills was restored to the captaincy of the Victoria team in 1876 in spite of grave misgivings about his alcoholism. Cricket columnist William Hammersley, writing under the pseudonym of ‘Longstop’, was frequently very vocal in his columns about the incidence of alcoholism among cricketers, frequently citing Tom Wills in particular. It soon became commonplace for several Sydney newspapers, notably the Sydney Punch, to lampoon Wills publicly in their columns.

In 1877, Wills wrote to the MCC Committee, as follows: “Seeing by advertisement that applications are to be sent in to you for the Office of Secretary to the MCC I herewith apply for same. I am well up in the duties attached to the office and do not fear work, and I trust that the Committee will give my application a favourable consideration, owing to my many years devotion to Colonial Cricket.” Although he had held the office previously in 1857 as a brash, swaggering 22-year old, the request was turned down this time. It is conjectured that this particular refusal was to be the final straw that broke the back of his mental balance, such as it was, at this stage of his life.

Gregory Mark de Moore takes us through the last tormented phase of the life of Tom Wills. He was admitted to Melbourne Hospital in 1875 with an episode of scarlet fever, at a time when columnist John Stanley James, writing under the nom-de-plume of “The Vagabond”, had depicted in graphic details the pitiable state of the Hospital, with its over-crowded wards and outpatients’ department, and about the paucity of trained medical personnel.

The alcohol-induced mental degeneration of Wills continued to progress at a rapid rate and he had to be admitted to hospital in Apr/1880 after his local medical practitioner, Dr John Bleeck, paid him a home visit and advised hospitalisation for observation and necessary action. Things soon got worse after he was discharged from hospital, and his de facto partner Sarah Theresa Barbour, finding Wills unable to sleep on the morning of 1 May/1880, thought it prudent to admit him in hospital again, this time in Ward 21, for Males only. His attending physician, Dr Patrick Moloney, one of the first two Medical Graduates in 1867 of the newly commissioned Melbourne University School of Medicine, and the only one from the batch to be fully trained in Australia, was by then a prominent Melbourne physician and co-editor of the Australian Medical Journal, besides being a member of the Melbourne Cricket Club.

The hospital record for 1 May, 1880 reads: “Thomas Wills, age 45, admitted 1/5/80 …. Patient admitted in a semi Delirium Tremens state… tremulous movements of hands… was rather obstinate… refused to remain in hospital.” It is not clear how Wills managed to abscond from hospital at about 5:00 PM on that Saturday evening and get back unaided to his rented residence at Jika Street, Heidelberg, about 8 miles away, in his unfit condition on that day, given that he had already been sedated with bromides, a popular contemporary treatment for delirium tremens.

Neighbours noted his agitated form on the first-floor veranda at about 9:00 PM the same night, muttering to himself and gesticulating in a wild manner. According to the evidence given by Sarah Theresa Barbour later, Wills had been so restless that she had felt it necessary to summon Constable John Hanlon at about 03:00 AM of May 2, 1880. On arrival, the constable and his junior assistant Thomas Murphy had initially advised that Wills be sent to the local lock-up for proper restraint. When Sarah was not willing to do that, the constables had advised her to employ someone to look after Wills. Accordingly, a labourer named David Dunwoodie had been entrusted with the duty of caring for Wills. At about 1:00 o’clock in the afternoon of 2 May, seeing Wills walking about in the garden, Dunwoodie had taken permission from Sarah to go home for his lunch.

Soon after the departure of Dunwoodie for his lunch, Wills had entered the kitchen and, taking up a pair of scissors, opened it and stabbed himself three times in the chest before his partner could react. He was reported to have died almost immediately. It appears that the inquest had been carried out in the Heidelberg home of the deceased Tom Wills by coroner Dr Richard Youl. After hearing all the evidence presented, the jurors had been of the opinion that: “at Heidelberg in the second of May current the deceased Thomas Wentworth Wills killed himself when of unsound mind from excessive drinking.”

While several medical explanations had been put forward at the time as being the causative factors in the tragedy, the most popular verdict being the issue of delirium tremens caused by a long-standing history of alcoholism, in hindsight, it seems reasonable to surmise that there may have been an element of Korsakoff’s Psychosis in the unfortunate manner in which Thomas Wills had chosen to end his earthly life. Surprisingly, the death certificate had reported that Thomas Wills’ parents were unknown. This seems very strange given that he had been the scion of a very well-known family of Victoria, and that his father Horatio had been a prominent public figure of his generation.

The remains of Tom Wills were laid to rest at Heidelberg cemetery after a brief Anglican service. Although the ceremony had not been attended by any member of the Wills extended family, the Lord Mayor of Geelong and the family financial advisor William Ducker had been both entrusted by the family with the task of selecting a suitable burial spot for Wills, with the family bearing all the expenses for the internment. It was reported that only Sarah Theresa Barbour, Wills’ de facto partner, had been in attendance at the cemetery.

The intriguing and poignant story of one of the most iconic sportsmen of Australia in the second half of the nineteenth century had thus ended on a most unfortunate and sombre note.

The remaining days of Charles Lawrence

Meanwhile, upon the return of the 1868 tourists to Australia, Charles Lawrence sold off his Manly hotel as it had not been doing well of late. In his 40s now, Lawrence decided to relocate further up the coast at Newcastle, at the mouth of the Hunter River. While at Newcastle, Lawrence worked for the NSW Railways for a period of about 24 years, playing cricket occasionally. At the age of about 43 years, Lawrence married a second time in 1871, his new bride being the Yorkshire-born Emmaretta Denison. The couple had three daughters, two of whom died in their infancy. Emmaretta was to predecease her husband, passing away in Dec, 1915.

He was in his 55th year when, together with his son, Charles Lawrence turned out for XVIII of Newcastle against Ivo Bligh’s touring England team, the 2-day game being played at Newcastle between 8th and 9th Dec, 1882. Lawrence’s contributions with the bat amounted to 5 and 0. Although both father and son are seen to have bowled in the visitors’1st innings of 339 all out, neither could capture any wickets in the drawn game.

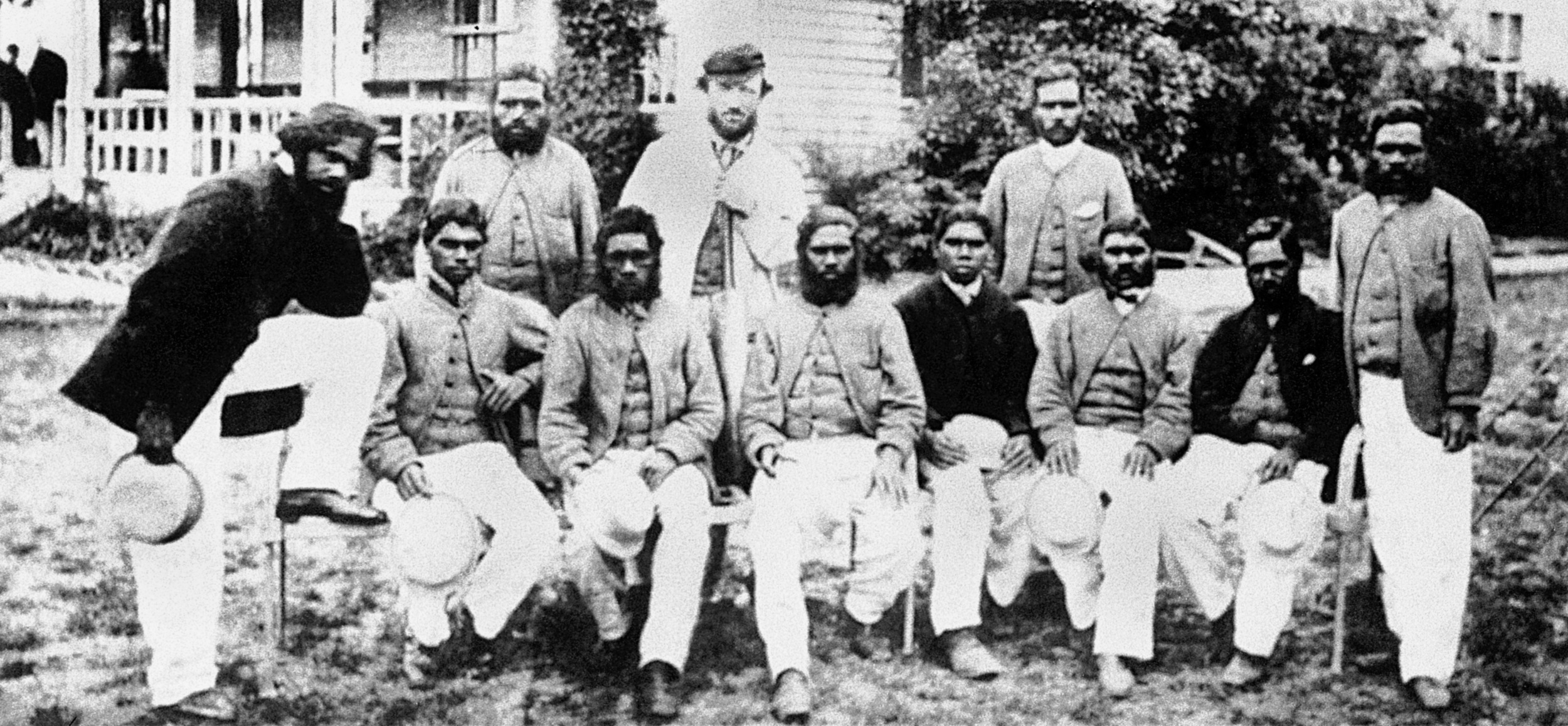

In 1892, the 64-year old Lawrence was compelled to retire from his NSW Railways sinecure on account of his indifferent health. He then moved to Melbourne where he accepted a coaching appointment with the Melbourne Cricket Club. Dogged by ill-health, he nevertheless kept his interests in cricket alive until he was in his 70s. Indeed, there is an old, faded photograph showing the 70-year old Lawrence in his batting stance while coaching his wards.

The scoring book shown in the accompanying picture (at the beginning of this article) is a copy of the original hand-written record maintained by Charles Lawrence of the games played by the Aboriginal cricketers against local teams of Victoria and New South Wales prior to embarking on their tour of England in 1868, and has been released by Andrew Leech, a great grandson of Charles Lawrence. It seems that this hand-written score-book had been handed down by several generations of the Lawrence and Leech families.

In 1911, a function was arranged to celebrate 50 years of Anglo-Australian cricket. Though invited, Lawrence was too infirm by then to attend the event that had been attended by the Governor-General, the Australian Prime Minister, and several ex-players from both England and Australia. His written apology for being unable to attend the historic event had included the lines: “ I am in my eighty fourth year but my interest in the game remains as great as it was, when in May 1849, playing for Scotland in Edinburgh, I bowled out the whole of the England XI," referring to his remarkable feat of capturing all 10 wickets of the AEE XI 2nd innings for 53 runs, while playing for Scotland at Edinburgh against the AEE XI in May/1849. Needless to say, his letter, when read out, was received rapturously.

A great pioneer and visionary of his generation, Charles Lawrence passed away on 20 Dec, 1916 at Melbourne. His entire cricket philosophy may have been summed up in the words with which he had begun to pen his childhood memories: “I had a greater love for cricket than for any other amusement and from early morn till late at night I was to be seen with bat and ball."